The Korean War: A History (16 page)

Read The Korean War: A History Online

Authors: Bruce Cumings

Most Americans seem unaware that the United States occupied Korea just after the war with Japan ended, and set up a full military government that lasted for three years and deeply shaped postwar Korean history. The laws of warfare and postwarfare distinguished between “pacific” (that is, peaceable) occupations of victimized populations, where interference in their internal affairs was prohibited, and “hostile” occupations in enemy terrain. The State Department instantly determined that Korea was a victim of Japanese aggression, but the occupation command time and again not only treated the South as enemy territory but at several points actually declared it to be such (especially in the southeastern provinces), and interfered in its politics to the degree that no other postwar regime was so clearly beholden to American midwifery.

The social and political forces that spawned the Korean civil war went back into the period of Japan’s colonial rule in Korea and

Manchuria, particularly to land inequities, to the anti-Japanese resistance of some Koreans and the collaboration with Japan of others, and to the staggering dislocation of ordinary Koreans, particularly in the decade 1935–45, when millions were moved around to service Japan’s vast industrialization and war mobilization efforts. By the end of the war fully one fifth of the population ended up abroad (usually in Japan or Manchuria) or laboring in a province other than their own (usually in northern Korea). The “comfort women” and the 200,000-plus Korean soldiers were the obvious victims, but millions of ordinary Koreans were exploited in mines, factories, forced labor details, and the like; tellingly, 10 percent of the entire population (2.5 million) was in Japan in 1945, compared with only 35,000 Taiwanese. Since the migrants were unlikely to be under twelve or over sixty, this was a very large chunk of a people that theretofore had clung tightly to the towns and villages of their birth. They all wanted to return to their hometowns when Japanese rule collapsed, and the vast majority were from southern Korea, home to major “surplus” populations.

After Pearl Harbor, American policy toward Korea shifted dramatically. The United States had never questioned Japanese control of Korea after 1905, when Theodore Roosevelt was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for arranging the Portsmouth Treaty ending the Russo-Japanese War, and blessed what he took to be Japanese “modernizing” efforts in Korea. By mid-1942, however, State Department planners began to worry that a Korea in the wrong hands might threaten the security of the postwar Pacific, and made plans for a full or partial military occupation of Korea upon Japan’s defeat. Franklin Roosevelt had a shrewder policy, a four-power “trusteeship” for Korea (the United States, the USSR, Britain, and Nationalist China) that would get Japanese interests out and American interests in, while recognizing the Soviet Union’s legitimate concerns in a country that touched its border. Roosevelt had entirely unrealistic visions of how long a trusteeship might last (forty or fifty years, perhaps), but he pushed the idea several times in

wartime discussions with Churchill and Stalin, and as the policy evolved it might have worked to keep Korea in one piece. The atomic bombings brought the Pacific War to an abrupt close, however, and with Truman now in the Oval Office, State Department bureaucrats pushed through an occupation policy.

Within a week of landing in Seoul, the head of XXIV Corps military intelligence, Col. Cecil Nist, had found “several hundred conservatives” who might make good leaders of postwar Korea. Most of them had collaborated with Japanese imperialism, he wrote, but he expected that taint soon to wash away. This pool of people held most of the leaders who would subsequently shape South Korean politics. The collaborationist nature of the anointed hundred led Hodge to seek a patriotic figurehead; the Office of Strategic Services found its man in Syngman Rhee, an exile politician who had haunted and irritated Foggy Bottom for decades. He was hustled aboard a military plane over State Department objections, flown to Tokyo, where he met secretly with MacArthur, and then deposited in Seoul by MacArthur’s personal plane,

The Bataan

, in mid-October 1945. Rhee understood Americans and their reflexive, unthinking, and uninformed anticommunism, and made that his stock-in-trade until 1960, when the Korean people finally threw him out in a popular rebellion. Because he had been gone so long from Korea and had few relatives, he was also a master at manipulating the family and regional ties of those below him. An obstinate man known for pushing things to the brink, he quickly convinced Americans that after him came chaos, beyond his leadership was the abyss.

A short two years into the occupation, the fledgling CIA issued a report stating that South Korean political life was “dominated by a rivalry between Rightists and the remnants of the Left Wing People’s Committees,” described as a “grass-roots independence movement which found expression in the establishment of the People’s Committees throughout Korea in August 1945.” As for the ruling political groups,

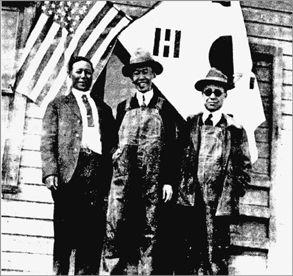

Syngman Rhee (right), at the office of the Association of the Friends of Korea, Denver, in 1920.

Courtesy of An Hyong-Ju

*

The leadership of the Right

[sic]

… is provided by that numerically small class which virtually monopolizes the native wealth and education of the country. Since it fears that an equalitarian distribution of the vested Japanese assets [that is, colonial capital] would serve as a precedent for the confiscation of concentrated Korean-owned wealth, it has been brought into basic opposition with the Left. Since this class could not have acquired and maintained its favored position under Japanese rule without a certain minimum of “collaboration,” it has experienced difficulty in finding acceptable candidates for political office and has been forced to support imported expatriate politicians such as Rhee Syngman and Kim Koo. These, while they have no pro-Japanese taint, are essentially demagogues bent on autocratic rule.

Syngman Rhee speaking at the welcoming ceremony for allied forces, October 20, 1945, with Gen. John Reed Hodge seated to his right.

U.S. National Archives

The result was that “extreme Rightists control the overt political structure in the U.S. zone,” mainly through the agency of the Japanese-built National Police, which had been “ruthlessly brutal in suppressing disorder.” The structure of the southern governmental bureaucracy was “substantially the old Japanese machinery,” with the Home Affairs Ministry exercising “a high degree of control over virtually all phases of the life of the people.”

2

The late 1940s were indeed the crucible of Korean politics thereafter, with a tremendous and indelible responsibility left at the American doorstep.

Both powers, of course, set about supporting domestic forces that suited their respective interests and worldviews. But American occupation leaders took several decisive actions late in 1945—reestablishing the colonial national police, setting up a fledgling army, bringing Syngman Rhee back from exile in the United States, and moving toward a separate southern government—that came more hastily than Soviet decisions to create a functioning government in the North. Furthermore, the United States had to impose its plans against a “Korean People’s Republic,” independent of the Northern version, that had been proclaimed in Seoul on September 6, and which spawned hundreds of “people’s committees” in the countryside. In December 1945 at a foreign ministers’ conference, the United States and the Soviets agreed on a five-year bilateral trusteeship for Korea, but actions taken by both commands in Korea made that agreement impossible to implement. By early 1946 Korea was effectively divided and the two regimes and two leaders (Rhee and Kim Il Sung) who founded the respective Korean states in 1948 were effectively in place.

Kim Il Sung speaking at Pyongyang celebration of independence from Japan, October 14, 1945. The Soviet generals who were behind him on the platform have been whited out by North Korean censors.

North Korea; U.S. National Archives

The commander of the occupation, General Hodge, was a sincere, honest, and unpretentious person with a sterling reputation as a warrior (“the Patton of the Pacific”). But as a military man he worried most about the political, social, and economic disorder that was everywhere around him. Within three months of his arrival he “declared war” on the Communist party (the one in the southern zone; he mistook a mélange of leftists, anticolonial resisters, populists, and advocates of land reform for “Communists”); in the spring of 1946 he issued his first warning to Washington of an impending North Korean invasion; and against direct instructions from Washington, at the end of November 1945 he began forming a native Korean army.

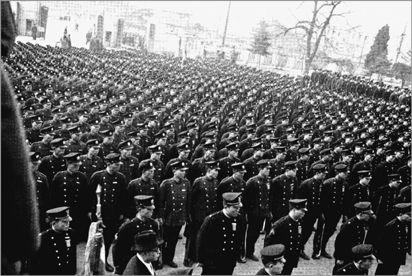

A Korean National Police unit at muster, circa 1946.

U.S. National Archives

The English Language School for officers founded in December was father to the Korean Constabulary Training Center established in May 1946, which in turn was father to the Korean Military Academy, renamed just after Rhee was inaugurated in 1948 and modeled on West Point. This academy graduated the plotters of the ROK’s

first military coup in 1961 (led by the eighth class) and the subsequent military coup in 1980 (class of ’55). Chong Il-gwon, for example, a captain in the Japanese Kwantung Army and (after the war) ROKA chief of staff and later prime minister, came out of the English Language School. In the fall of 1946 the second class of officers graduated from the academy: in it were Park Chung Hee, who led the 1961 coup, and the head of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA) who murdered him in 1979, Kim Chae-gyu; both had been officers in the Japanese military in Manchukuo. The U.S.-sponsored Combat Intelligence School was renamed the Namsan (South Mountain) Intelligence School in June 1949, and later became the dreaded torture chamber of the KCIA.

3

Resistance to these outcomes was much greater in southern Korea than in the North. A major rebellion shook the American occupation to its roots in October and November 1946, and was the culmination of numerous conflicts over previous months with locally powerful people’s committees. In October 1948 another big rebellion occurred in and around the southwestern port of Yosu, and after that guerrilla resistance developed quickly, most of it indigenous to the south. It had its greatest impact in southwestern Korea and on Cheju Island, and kept the U.S.-advised Korean Army and Korean National Police very busy in 1948 and 1949. Meanwhile, by early 1947 Kim Il Sung had begun to dispatch Koreans to fight on the Communist side in the Chinese civil war, and in the next two years tens of thousands of them gained important battle experience. These soldiers later became the main shock forces in the Korean People’s Army, and structured several divisions that fought in the Korean War.