The Korean War: A History (6 page)

Read The Korean War: A History Online

Authors: Bruce Cumings

Chinese forces attacked in late October, bloodied many American troops, and then disappeared. It is likely that the Chinese hoped this would suffice to stop the American march to the Yalu, perhaps at the narrow neck of the peninsula above Pyongyang. But this also would leave the DPRK as a small, rump regime. Around this time Kim Il Sung arrived in Beijing on an armored train, moving under cover of darkness and blanketed security. He was accompanied by three other uniformed Koreans, and China’s northeast leader, Kao Kang. High PRC leaders, including Chou En-lai and Nieh Jung-chen (the two besides Mao most closely linked to the Korean decision), were not seen in Beijing in the same period, reappearing for the funeral of Jen Pi-shih on October 27.

26

But the Americans resumed their advance, as did the North Korean–Chinese strategy of luring them deep into the interior of North Korea, thus to stretch their supply lines, wait for winter, and gain time for a dramatic reversal on the battlefield.

MacArthur and his G-2 chief, Charles Willoughby, trusted only

themselves, and had an intuitive approach to intelligence that mingled the hard facts of enemy capability with hunches about the enemy’s presumed ethnic and racial qualities (“Chinamen can’t fight”). This combined with MacArthur’s “personal infallibility theory of intelligence,” in which he “created his own intelligence organization, interpreted its results and acted upon his own analysis.”

27

When the CIA was formed it threatened MacArthur’s exclusive intelligence theater in the Pacific and J. Edgar Hoover’s in Latin America. MacArthur and Willoughby thus continued the “interdiction” that they practiced against the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in the Pacific War. Although the CIA did function in Japan and Korea before June 1950, operatives had to either get permission from Willoughby or hide themselves from MacArthur’s G-2 (as well as the enemy target). Effective liaison in the handling of information barely existed. At the late date of March 1950 some minimal cooperation ensued when Gen. J. Lawton Collins of the JCS asked that MacArthur share with them Willoughby’s reports on China and areas near to it.

On Thanksgiving Day (November 23) the troops in the field had turkey dinners with all the trimmings—shrimp cocktail, mashed potatoes, dressing, cranberry sauce, pumpkin pie. They did not know that thousands of Chinese soldiers surrounded them, carrying “a bag of millet meal” and wearing tennis shoes at 30°F below zero. (The North Koreans and Chinese had “one man back to support one man forward,” Thompson wrote; the Americans had nine back and one forward—and “scores of tins, of candy, Coca-cola, and toilet supplies.”)

28

The next day MacArthur launched his euphemistically titled “reconnaissance in force,” a general offensive all along the battle line. He described it as a “massive compression and envelopment,” a “pincer” movement to trap remaining KPA forces. Once again American and South Korean forces were able to run north unimpeded. The offensive rolled forward for three days against little or no resistance, with ROK units succeeding in entering the northeastern industrial city of Chongjin. MacArthur launched the marines toward the Changjin Reservoir (known by its Japanese name, Chosin, in the American literature) and sent the 7th Division north of the Unggi River, in spite of temperatures as low as 22 degrees below zero. Within a week the 7th Division had secured Kim Il Sung’s heartland of Kapsan, and reached Hyesan on the Yalu River against no resistance.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur surveys Korea from

The Bataan

on the eve of the “reconnaissance in force.”

U.S. National Archives

Finally CIA daily reports caught the pattern of enemy rearward displacement, arguing that such withdrawals had in the past preceded offensive action, and noting warily that there were “large, coordinated and well-organized guerrilla forces in the rear area” behind the Allied forces, along with guerrilla occupation of “substantial areas in southwest Korea.” But as late as November 20 the estimates were still mixed, with some arguing that the Communists were simply withdrawing to better defensive points, and others that the pattern of “giving ground invariably in face of UN units moving northward” merely meant “a delaying action,” not preparation for all-out assault. Lost amid the hoopla of victory by Christmas were reports from reconnaissance pilots that long columns of enemy troops were “swarming all over the countryside”—not to mention the retrieval of Chinese POWs from six different armies.

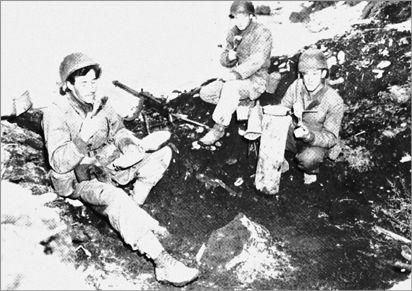

American soldiers enjoy Thanksgiving dinner on the banks of the Yalu, November 23, 1950.

U.S. National Archives

Strong enemy attacks began on November 27, through a “deep envelopment” that chopped allied troops to pieces. The 1st Marine Division was pinned down at the Changjin Reservoir, the ROK II Corps collapsed again, and within two days a general withdrawal ensued. On December 4 the JCS cabled MacArthur that “the preservation of your forces is now the primary consideration”—that is, the utterly overexposed core of the entire American expeditionary force, now battered and surrounded. Two days later Communist forces occupied Pyongyang, and the day after that the allied front was only twenty miles north of the parallel at its northernmost

point. The combined Sino-Korean offensive cleared North Korea of enemy troops in little more than two weeks from its inception. Gen. Edward Almond wrote that “we are having a glut of Chinamen”; he hoped he would have the chance later “to give these yellow bastards what is coming to them.” By the end of December, Seoul was about to fall once again, to a Sino-Korean offensive launched on New Year’s Eve.

29

MacArthur had described the first Sino-Korean feint as “one of the most offensive acts of international lawlessness of historic record”; the KPA, he told Washington, was completely defeated, having suffered 335,000 casualties with no forces left. Thus, “a new and fresh [Chinese] army now faces us.” (In fact, KPA forces far outnumbered Chinese at this point.) Then, when large Chinese units entered the fighting at the end of November, he radioed back that he faced “the entire Chinese nation in an undeclared war.” All the Chinese? Did he mean those famous “Chinese hordes”? There weren’t any, Reginald Thompson rightly said; in late 1950 the total of enemy forces in the North never outnumbered those of the UN, even though MacArthur’s headquarters counted eighteen Chinese divisions (somehow a few hundred POWs had fortuitously managed to come from each and every one of them).

30

The Chinese just exploited night maneuvers, deft feints, unnerving bugles and whistles, to make UN soldiers think they were surrounded.

As soon as Chinese troops intervened in force, MacArthur ordered that a wasteland be created between the war front and the Yalu River border, destroying from the air every “installation, factory, city, and village” over thousands of square miles of North Korean territory. As a British air attaché at MacArthur’s headquarters put it, except for the city of Najin near the Soviet border and the Yalu River dams, MacArthur’s orders were “to destroy every means of communication and every installation and factories and cities and villages. This destruction is to start at the Manchurian border and to progress south.”

31

This terrible swath of destruction, targeting every village in its path, followed Chinese forces right into

South Korea. Soon George Barrett of

The New York Times

found “a macabre tribute to the totality of modern war” in a village north of Anyang:

The inhabitants throughout the village and in the fields were caught and killed and kept the exact postures they held when the napalm struck—a man about to get on his bicycle, fifty boys and girls playing in an orphanage, a housewife strangely unmarked, holding in her hand a page torn from a Sears-Roebuck catalogue crayoned at Mail Order No. 3,811,294 for a $2.98 “bewitching bed jacket—coral.”

Secretary of State Dean Acheson wanted censorship authorities notified about this kind of “sensationalized reporting,” so it could be stopped.

32

On November 30 Truman also rattled the atomic bomb at a news conference, saying the United States might use any weapon in its arsenal to hold back the Chinese; this got even Stalin worried. According to a high official in the KGB at the time, Stalin expected global war as a result of the American defeat in northern Korea; fearing the consequences, he favored allowing the United States to occupy all of Korea: “So what?” Stalin said. “Let the United States of America be our neighbors in the Far East.… We are not ready to fight.” Unlike Stalin the Chinese were ready—but only to fight back down to the middle of the peninsula, rather than to start World War III.

Gen. Matthew Ridgway’s astute battlefield generalship eventually stiffened the allied lines below Seoul, and by the end of January he led gallant fights back northward to the Han River, opposite the capital. After more weeks of hard fighting, UN forces recaptured Seoul, and in early April, American forces crossed the 38th parallel again. Later that month the last major Chinese offensive was turned back, and by the late spring of 1951 the fighting stabilized along lines similar to those that today mark the Korean demilitarized

zone, with UN forces in occupation north of the parallel on the eastern side, and Sino–North Korean forces occupying swatches of land south of the parallel on the western side. That was about where the war ended after tortuous peace negotiations and another two years of bloody fighting (most of it positional, trench warfare reminiscent of World War I).

HE

S

USPENSION OF THE

W

AR

On June 23, 1951, the Soviet UN representative, Adam Malik, proposed that discussions get started between the belligerents to arrange for a cease-fire. Truman agreed, suggesting that representatives find a suitable place to meet, which turned out to be the ancient Korean capital at Kaesong, bisected by the 38th parallel. Truce talks began on July 10, led initially by Vice Adm. C. Turner Joy for the UN side, and Lt. Gen. Nam Il of North Korea. The talks dragged on interminably, with several suspensions and a removal of the truce site to the village of Panmunjom (where it remains today). Proper and fair demarcation of each side’s military lines caused endless haggling, but the key issue that drew out the negotiations was the disposition of huge numbers of prisoners of war on all sides. The critical issue was freedom of choice in regard to repatriation, introduced by the United States in January 1952; about one third of North Korean POWs and a much larger percentage of Chinese POWs did not want to return to Communist control. Meanwhile South Korea refused to sign any armistice that would keep Korea divided, and in mid-June 1953, Syngman Rhee abruptly released some 25,000 POWs—leading the United States to develop plans (“Operation Everready”) to remove Rhee in a coup d’état, should he try to disrupt the armistice agreement again. As usual, though, Rhee got his way: the Eisenhower administration bribed him with promises of a postwar defense treaty and enormous amounts of “aid”—and even then he refused to sign the armistice.