The Korean War: A History (19 page)

Read The Korean War: A History Online

Authors: Bruce Cumings

A month later an American colonel, Rothwell H. Brown, reported that Korean and American military units had interrogated fully four thousand inhabitants of Cheju, determining that a “People’s Democratic Army” had been formed in April, composed of two regiments of guerrillas; its strength was estimated at four thousand officers and men, although fewer than one tenth had firearms. The remainder carried swords, spears, and farm implements; in other words, this was a hastily assembled peasant army. Interrogators also found evidence that the SKWP had infiltrated no more than six “trained agitators and organizers” from the mainland, and none had come from North Korea; with some five hundred to seven hundred allies on the island, they had established cells in most towns and villages. Between 60,000 and 70,000 islanders had joined the party, Brown asserted, although it seems much more likely that such figures refer to long-standing membership in people’s committees and mass organizations. “They were for the main part, ignorant, uneducated farmers and fishermen whose livelihood had been profoundly disturbed by the war and the post-war difficulties.”

15

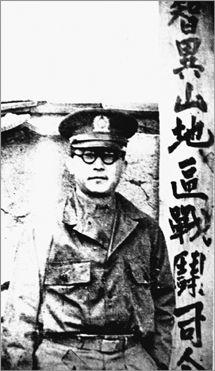

Yi Tok-ku was the commander of the rebels. Born in Shinchon village on the island in 1924 into a family of poor fishermen-peasants, he subsequently went to Osaka as a child laborer, as did his brother and his sister. He returned to Sinchon just after the liberation, and became a Workers’ Party activist. He was arrested and tortured for three months in 1947, and thereafter began organizing guerrillas.

16

The guerrillas generally were known as the

inmin-gun

, or People’s Army, but they were not centrally commanded and operated in mobile units eighty or a hundred strong that often had little connection with other rebels. This, of course, was one of the elements that made the movement hard to suppress. CIC elements found no evidence of North Korean personnel or equipment.

17

The police refused to admit any responsibility for the eruption

of the violence, blaming agitators from North Korea for the trouble. These organizers were able to stir up the population, the police thought, because “the learned and wealthy” had the habit of living on the mainland, leaving “only the ignorant” people on Cheju. It was necessary to appoint officials from the mainland, the police said, because local people were all interrelated and would not work “strongly and resolutely” in dealing with unrest. The KNP superintendent recommended that “patriotic young men’s associations” be promoted, and the institution of “assembly villages” to concentrate the population and drain rural support away from the guerrillas.

18

In his own report Colonel Brown said that the rebellion had already led to “the complete breakdown of all civil government functions”; the South Korean Constabulary had adopted “stalling tactics,” whereas “vigorous action was required.” People on the island were panicked by the violence, but they also would not yield to interrogators, even under torture: “blood ties which link most of the families on the Island … make it extremely difficult to obtain information.” Direct American involvement in suppressing the rebellion included the daily training of counterinsurgent forces, interrogation of prisoners, and the use of American spotter planes to ferret out guerrillas. One newspaper reported that American troops intervened in the Cheju conflict in at least one instance in late April 1948, and a group of Korean journalists even charged in June that Japanese officers and soldiers had secretly been brought back to the island to help in suppressing the rebellion.

On May 22, 1948, Colonel Brown developed the following procedures, to “break up” the revolt: “police were assigned definite missions to protect all coastal villages [from guerrillas]; to arrest rioters carrying arms, and to stop killing and terrorizing innocent citizens.” The Constabulary was told to break up all elements of the guerrilla army in the interior of the island. Brown also ordered widespread, continuing interrogation of all those arrested, and efforts to prevent supplies from reaching the guerrillas. Subsequently

he anticipated the institution of a long-range program “to offer positive proof of the evils of Communism,” and to “show that the American way offers positive hope” for the islanders. From May 28 to the end of July, more than three thousand islanders were arrested.

19

Following Japanese counterinsurgency practice, the entire island interior was declared an enemy zone, villagers were forcibly relocated to the coast, and the mountains—primarily the volcanic Mount Halla, which dominates the island—were blockaded. More than half of all villages on the mountain slopes were burned and destroyed, and civilians thought to be aiding the insurgents were massacred. Civilians were by far the largest category of victims, some killed by the insurgents, but the vast majority by police and right-wing youth squads. Women, children, and the elderly who were left behind were tortured to gain information on the insurgents, and then killed. Col. Kim Yong-ju brought three thousand soldiers in the Constabulary’s 11th Regiment back to the mainland in early August, and told reporters that “almost all villages” on the island were vacant, the residents having fled either to the protection of guerrillas in the interior or to the coast. He implied that far more had gone into the mountains. “The so-called mountain man is a farmer by day, rioter by night,” the Cheju Constabulary commander said; “frustrated by not knowing the identity of these elusive men, the police in some cases carried out indiscriminate warfare against entire villages.” When the Constabulary refused to adopt the same murderous tactics, the police called them Communists. A KMAG account in late 1948 cited “considerable village burning” by the suppression command; three new Constabulary battalions were being recruited, the report said, “mainly from Northwest Youth.” Islanders were now giving information on the guerrillas—apparently because their homes would be burned if they did not.

20

The 9th Regiment of the Constabulary later got control of several points in the highlands, and herded village people toward the coasts, enabling them to starve out guerrillas and push them out of

their mountain redoubts. Naval ships had completely blockaded the island, making resupply of guerrillas from the mainland impossible.

21

By early 1949 more than 70 percent of the island’s villages had been burned out. In April things got worse:

Cheju Island was virtually overrun early in the month by rebels operating from the central mountain peak … rebel sympathizers numbering possibly 15,000, sparked by a trained core of 150 to 600 fighters, controlled most of the island. A third of the population had crowded into Chejoo town, and 65,000 were homeless and without food.

22

By this time 20,000 homes on the island had been destroyed, and one third of the population (about 100,000) was concentrated in protected villages along the coast. Peasants were allowed to cultivate fields only near perimeter villages, owing to “chronic insecurity” in the interior and the fear that they would aid the insurgents.

23

Soon, however, the guerrillas were basically defeated. An American Embassy official, Everett Drumwright, reported in May 1949 that “the all-out guerrilla extermination campaign … came to a virtual end in April with order restored and most rebels and sympathizers killed, captured, or converted.” Ambassador John Muccio wired to Washington that “the job is about done.” Shortly it was possible to hold a special election, thus finally to send a Cheju islander to the National Assembly; none other than Chang Taek-sang, the longtime head of the Seoul Metropolitan Police, arrived to run for a seat.

24

By August 1949 it was apparent that the insurgency had effectively ended and the rebel leader Yi Tok-ku was finally killed. Peace came, but it was the peace of a political graveyard.

American public sources reported in 1949 that 15,000 to 20,000 islanders died, but the ROK’s official figure was 27,719. The North Koreans said that more than 30,000 islanders had been “butchered”

in the suppression. The governor of Cheju, however, privately told American intelligence that 60,000 had died, and as many as 40,000 people had fled to Japan; officially 39,285 homes had been demolished, but the governor thought “most of the houses on the hills” were gone: of 400 villages, only 170 remained. In other words, one in every five or six islanders had perished, and more than half the villages were destroyed.

25

The Northwest Youth now ran Cheju and continued “to behave in a very arbitrary and cruel manner” toward the islanders, according to Americans on the scene; “the fact that the Chief of Police was a member of this organization made matters even worse.” Like Stanley Kubrick’s

A Clockwork Orange

, where the “droogies” turned into police, the NWY not only worked closely with the National Police, but soon entered its ranks wholesale. By the end of 1949, three hundred members of the Northwest Youth had joined the island police, and two hundred were in business or local government: “the majority have become rich and are the favored merchants.” The senior military commander and the vice-governor were also from north Korea. Of course, “the rich men of the island” were once again influential, too, “despite the fact that governmental control has changed three times.” About three hundred “emaciated” guerrillas remained in the Cheju city jail, and another two hundred were thought to be still on the loose, but inactive. Peasants and fishermen had to have daily police passes to work the fields or the ocean.

26

Just before the war began in June 1950, a U.S. Embassy survey found the island peaceful, with no more than a handful of guerrillas. During the warfare at the Pusan perimeter, Americans reported that police had collected radios from the entire island population, so they could not find out about the North Korean advance on the mainland; the only telephone network was controlled by the police, and would be the main means of communication should the North Koreans seek to invade the island. Americans surmised, however, that a “subversive potential” still existed on Cheju, because of “an

estimated 50,000 relatives of persons killed as Communist sympathizers in the rebellion.” Fully 27,000 of the islanders had been enrolled in the National Guidance Alliance, an organization set up by the state to convert leftists. In 1954 an observer of Cheju wrote, “Village guards man watchtowers atop stone walls; some villages have dug wide moats outside the walls and filled them with brambles, to keep bandits out.”

27

Dr. Seong Nae Kim has given eloquent voice to Cheju survivors, whose repressed memories of violence surface in dreams or in sudden apparitions—ghosts, spirits, the conjurings of a shaman, or fleeting glimpses of loved ones “in blood-stained white mourning clothes.” The widow of an insurgent is hounded by the police into autism, catatonia, and suicide. Families cannot even utter the name of the dead or perform ancestor rituals, for fear of blacklisting; if one relative was labeled a Communist, the entire family’s life chances were jeopardized under the Law of Complicity (

yonjwa pop)

. Forgetting was the immediate cure for such suffering, but its comforts were temporary. Memory surfaces apart from one’s intentions, the deceased return in dreams, the terror recurs in nightmares. The mind compensates for loss and adapts to the dictate of the state: if your brother was killed by a right-wing youth squad, say the Communists killed him. Time passes, and the bereaved turns this reversal into the recalled truth. But the mind knows it is a lie, and so psychic trauma returns in terrible dreams, or the apparition of an accusing, vengeful ghost.

28

HE

Y

OSU

R

EBELLION

As the Cheju insurgency progressed, an event occurred that got much more attention, indeed international coverage: a rebellion at the southeastern port city of Yosu that soon spread to other counties, and that for a time seemed to threaten the foundations of the fledgling republic. The proximate cause of the uprising was the refusal on October 19, 1948, of elements of the 14th and 6th regiments of the ROK Army to embark for a counterinsurgency mission on Cheju. Here, too, the commanders who actually subdued the rebels were Americans, assisted by several young Korean colonels: Chong Il-gwon, Chae Pyong-dok (“Fatty” Chae to Americans), and Kim Paek-il. Gen. William Roberts, the KMAG commander, ordered Americans to stay out of direct combat, but even that injunction was ignored from time to time. American advisers were with all ROK Army units, but the most important ones were Col. Harley E. Fuller, named chief adviser for the suppression, Capt. James Hausman from KMAG G-3, and Capt. John P. Reed from G-2 (Army intelligence).

29