The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (30 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

To the victor, the spoils. The defeat of the Spanish Armada provided the opportunity for a great wave of celebratory pamphleteering, in England, the Netherlands and Germany.

50

The vanquished licked their wounds in silence. The presses of Italy, so busy after Lepanto, had little to offer. France was mostly consumed by its own affairs, though the Parisian press did briefly rouse itself to report a Spanish victory off the Orkney Islands as the returning fleet made its long and tortuous way home.

51

This again seems to have been largely wishful thinking, though similar reports were clearly circulating in Antwerp.

52

England had been badly shaken by the events of the summer. Preachers spreading blood-curdling rumours that the Spanish planned to kill every man between seven and seventy might have encouraged desperate resistance, or they might have caused morale to collapse altogether. Calls for repentance mixed with invocations of divine favour also risked drawing attention to the ramshackle nature of military preparations. When the Armada achieved its rendezvous with Parma without substantial loss, some began to criticise the admiral's apparent lack of boldness in handling his fleet. But as the scale of the victory became known, all was forgiven. Queen Elizabeth's speech at Tilbury was witnessed by a number of aspiring authors keen to perpetuate its memory. Two agile and enterprising entrepreneurs returned to London and registered ballads celebrating the speech the very next day. These Tilbury ballads were part of a cascade of cheap print as London's often under-employed printers cashed in on the mood of national celebration.

53

James Aske, whose

Elizabetha Triumphans

was an altogether more ambitious literary work, at one point despaired of seeing it printed at all, because ‘of the commonness of ballads’. With the danger now past it was time to mock recent fears. It was widely reported that on board the captured Spanish ships had been found large numbers of whips and leg-irons, clearly to enslave and torment the conquered nation. This was cheerfully satirised in a blood-curdling ballad illustrated with woodcuts of the whips.

54

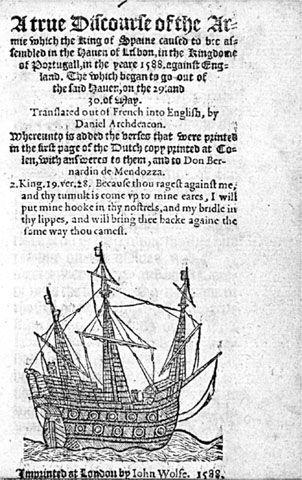

One of the most subtle pieces of government-sponsored propaganda was an English version of the Spanish pamphlet listing the ships, munitions and men of the Armada.

55

The original, printed at the time of the fleet's embarkation in Lisbon, had been republished in French by Mendoza during the summer.

56

Now England threw back in his face the battle array of the ‘invincible’ fleet, vanquished by England's mariners and God's will. All told, we can detect a new confidence, wit and polemical flair in the English pamphlet literature of

these years, epitomised by

A pack of Spanish lies

, a typographically subtle piece that presented the Spanish claims of the summer, in a ponderous Gothic type, alongside a corrected narrative in sprightly Roman.

57

We are the future now, it seemed to say: thus was false news held up to ridicule. At the beginning of a decade when news of continental wars would consume the London press, England's printers were taking significant steps towards the development of the fully fledged news market that had hitherto eluded them.

7.6 The might of the Spanish fleet. After its defeat this enumeration of the vessels and their armament was a celebration of English naval prowess.

The Spider's Web

The common thread in all three of these instances is the Spanish king, Philip II. He had organised and financed the expedition that had ended with the

victory of Lepanto. He was widely suspected of being the evil genius behind the massacre of 1572, particularly (but not exclusively) in Protestant Europe. The Armada of 1588 was to have been the crowning enterprise of his grand design, to save Europe for Catholicism and put his enemies – in England, France and the Low Countries – to flight. Its failure dashed these hopes and condemned Europe to a brutal decade of attritional warfare.

Philip ruled Spain at the height of its powers. It was Europe's military superpower, its armies paid by the seemingly inexhaustible bullion extracted from the silver mines of Potosí (now in Bolivia) in the viceroyalty of Peru. From 1580 Philip also had at his disposal the resources of Portugal, and especially its deep-water fleet. No wonder that Spanish plans and ambitions were the constant concern of international diplomacy and the European news market. Yet Philip himself remained a rather mysterious presence, or, more correctly, absence, inscrutable and seldom seen. From the time of his return to Spain from the Netherlands in 1559 he never again left the peninsula. He spent the later decades of his reign at the newly built monastery palace El Escorial, deliberately remote from Spain's major towns. From here he attempted to manage a foreign policy of sustained and unprecedented ambition.

It is worth concluding our survey of the effectiveness of Europe's sixteenth-century news networks by contemplating the events of this period from Philip's perspective. For all Spain's military might, it remained during Philip's reign, as it had been in the previous two centuries, somewhat remote from the main European highways. The correspondence of medieval merchants had been mostly with the Mediterranean ports (especially Barcelona) not the Castilian interior. The rising power of Seville was, like Lisbon, orientated towards the Atlantic rather than main European trade routes. When Philip decided on Madrid as the main base of his operations, this required significant adjustments to the postal infrastructure. In 1560 a new ‘ordinary’ post was established between Madrid and Brussels. This passed by Burgos and Lesperon, and then through France via Poitiers, Orléans and Paris. When the king moved residence, in what became an increasingly fixed annual routine, the central administration remained in Madrid. Documents were brought to him in the Escorial or elsewhere by daily courier. The establishment of the ordinary post led to a great increase in the volume of mail and a commensurate reduction of cost; but it also meant that a great deal of routine diplomatic traffic was reaching Madrid by non-secure routes. This, and the normal hazards of postal communication, encouraged Spanish diplomats to adopt the prudent practice of sending duplicates of important despatches. On 15 August 1592 the king's ambassador in Savoy wrote to inform him:

On the second of this month I dispatched a letter to Your Majesty on a frigate from Barcelona whose owner is named Bernardino Morel and I included the copy of the dispatches of the 8, 10, 17 and 21 July and in view of the good prevailing weather I trust that they will have arrived so long as no ship has cut them off.

58

This of course meant that Madrid frequently received several copies of the same despatch.

Direct communication with Madrid was only one part of the vast official correspondence maintained by Philip's agents abroad. The instructions communicated to a new ambassador in Paris in 1580 required him in addition to maintain correspondence with the governors of Milan and Flanders, the viceroy of Naples and ambassadors in Rome, Venice and Germany. Communication with some of the most distant outposts was especially challenging. Post from the imperial court at Prague could take up to five months to arrive in Spain, and sometimes was lost altogether.

59

Even an arterial route like the sea lanes between Naples and the Iberian Peninsula only operated for part of the year: between 15 November and 15 March the galley fleet was laid up because of the difficult and stormy conditions of the Mediterranean in winter. Post then had to be carried along the circuitous landward route via Genoa and Barcelona.

Maintaining efficient contact with his network of ambassadors, agents and allies was for Philip both complex and expensive, even in the best of times. But these times were far from normal, thanks, not least, to the incessant warfare stimulated by his own policies. The quality of the postal network clearly deteriorated in the second half of the sixteenth century.

60

Delays multiplied and the security of the post was frequently compromised. Most urgent was the interruption to the post caused by the wars in France. The arterial route between Barcelona and Italy passed through southern France to Lyon. By 1562 two of the crucial staging posts on this route, Montpellier and Nîmes, were in Huguenot hands, and couriers were frequently searched or robbed on the journey. On the northern route to Brussels the heavily wooded area around Poitiers was notorious for brigandage. In 1568 a Spanish royal courier was waylaid and murdered, and attempts to retrieve the diplomatic pouch were unsuccessful. It was soon recognised that the French transit routes were too hazardous. But avoiding France involved either a circuitous journey along the imperial post roads through the Empire, or using ships through the English Channel, where Spanish vessels faced increasing hazards from Calvinist privateers operating out of English ports or La Rochelle.

In Brussels, the Duke of Parma faced particular problems in communicating with Philip II in time of war. On one occasion in 1590 he sent five

copies of one despatch to ensure its arrival. Sometimes, it must be admitted, these logistical difficulties could be used to advantage. When Parma was asked in December 1585 to prepare an operational plan for the invasion of England, he took until April 1586 to reply. He then chose to send his report by the longest possible route, via Luxembourg and Italy, with the result that it arrived in Madrid on 20 July. This, as Parma was clearly aware, rendered a campaign that year impossible, and allowed him to keep his army intact for the war against the Dutch for another fighting season.

61

The vagaries of the post also spared the Venetian ambassador in Madrid embarrassment during Armada year. As we have seen, on 17 August the Venetian Senate voted to offer Philip congratulations on his famous victory. Happily these instructions arrived in Madrid only on 2 October, by which time the scale of the catastrophe was becoming clear. The ambassador thought it best to ignore the despatch.

The information network constructed by Philip was on paper impressive. But in practice the logistical difficulties under which it operated meant that a vastly increased volume of communication was combined with decreased efficiency: Philip was being drowned in stale news. These difficulties were compounded by the manner in which he chose to conduct business. Philip developed a style of government that deviated sharply from the accepted conduct of princes. At all points possible he avoided meetings. Papers were brought to him, and he considered them in private. This had a certain rationality: there were so many people wanting the king's ear, including the large residential diplomatic corps, that even to meet ambassadors on a regular basis would have been inordinately time consuming.

62

Some accommodated themselves to the king's preferences. The French ambassador Fourquevaux, instructed to seek an audience, instead sent a letter. ‘I know that I would please him more if I communicated with him by letter,’ he explained to Charles IX, because ‘he prefers ambassadors to deal with him by letter rather than in person while he resides in his country houses.’

63

Others, including the papal nuncio, who had been unable to secure an audience for four months, proved less understanding.

Nothing could disguise that this was completely at variance with the normal traditions of court life, and many of King Philip's subjects expressed their disapproval. ‘God did not send your Majesty and all other kings to spend their time on earth so that they could hide themselves away reading and writing,’ wrote the king's almoner, with alarmingly frank courage. He went on to denounce ‘the manner of transacting business adopted by Your Majesty, being permanently seated at your papers in order to have a better reason to escape from people’.

64

Philip was not a recluse. He understood the value of showing himself to his people, and on such occasions the population responded with enthusiasm. He

seems simply to have felt that the business of government could most effectively be conducted by reading. Theoretically his father Charles V had established a highly efficient system to sort and order the papers that flowed into the chancery. Councils were named to deal with the affairs of each province, and separately with war, finance and forestry. But Philip still insisted on taking all decisions himself. He rarely attended Council meetings, and was disinclined to join discussions between his advisors. High-ranking officials were not encouraged to return to Spain for debriefing between postings. Philip therefore chose to forgo important opportunities for detailed conversations with informed experts and advisors. He also completely discontinued the common practice of sending trusted messengers with oral instructions: all was set down in writing.