The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (34 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

The First Newspapers

I

N

the year 1605 a young book dealer named Johann Carolus appeared before the Strasbourg city council with an unusual request. Besides his bookselling Carolus had recently also developed a lucrative sideline, producing a weekly manuscript newsletter. By this date, as we have seen, the manuscript newsletter had become the cornerstone of the information market for Europe's elites. From its early days in Rome and Venice, the production of manuscript newsletters had now spread across Germany, and from Augsburg and Nuremberg to Brussels and Antwerp in the Low Countries. Strasbourg, situated close to the crucial Rhine crossing serving the imperial post service at Rheinhausen, was extremely well placed for such a venture. Carolus could be sure of a steady supply of news from the imperial postmaster and the constant passage of commercial traffic. And in a busy city like Strasbourg he would not have been short of customers.

His enterprise clearly prospered; by 1605 Carolus was in the position to diversify further by buying a print shop. He now conceived a plan to mechanise his existing trade in manuscript newsletters by producing a printed version. In a neat echo of Gutenberg and the invention of print one hundred and fifty years before, this was a logical response to a situation where increasing demand was straining the capacity of existing technology to deliver adequate quantities. But the investment costs, not least in buying his printing press, had stretched Carolus's resources, so now he turned to the city council for help. He told them that he had already produced twelve issues of his printed newsletter. But he obviously feared that if it proved successful others would try to copy him and wipe out his profits. So he asked the council to grant him a privilege – that is, a monopoly – on the sale of printed newsletters.

1

This was not unreasonable. Any entrepreneur who believed he had pioneered a new industrial or manufacturing process would seek protection

against interlopers copying his innovation, and such privileges were common in the book world.

2

Carolus had good reason to hope that members of the Strasbourg city council, who made up a large part of his client base, would be sympathetic.

For an event of such momentous consequences Carolus's intentions were surprisingly modest. He merely sought a way to simplify a process that currently involved writing by hand an increasing number of copies, and thus to speed production. The output itself would not be essentially different: still the same sequence of bald news items familiar from his manuscript news service. But from this modest, rather tentative transaction emerged a new form of communication that would in due course transform the European news market: Carolus had invented the newspaper.

The Rise of the North

If Carolus did begin publishing his newspaper, the Strasbourg

Relation

, in 1605, the earliest issues are unfortunately all lost: the first surviving copies date from 1609.

3

For this reason many older histories of the newspaper will time its beginnings from this later date; it is only relatively recently that the full significance of the discovery in the Strasbourg archive of Carolus's petition to the city council has been appreciated.

4

That four complete years of the earliest issues have simply disappeared is not at all surprising. It is very rare to find a complete run of the earliest newspapers, and many are known only from a handful of stray copies: sometimes only a single issue survives to attest to a newspaper's existence.

5

We can nevertheless be reasonably certain that Carolus did begin production in 1605. His petition to the council after all speaks of twelve issues already published. When we look at the first surviving copies from 1609, we see that these are certainly faithful to his stated intention that the newsprint would simply be a mechanised version of the handwritten newspaper. Individual issues have no title-heading: the title is given only in the printed title-page supplied to subscribers so that they could bind together the year's weekly issues. Instead the news begins, rather like the

avvisi

, at the top of the first page. In every respect the familiar pattern of the

avvisi

is retained: a sequence of news reports gathered by their place of origin and dated according to their date of despatch: ‘From Rome, 27 December'; ‘From Vienna, 31 December & 2 January'; ‘From Venice, 2 January’. The order reflects the sequence in which the posts from these various stations arrived in Strasbourg. The contents were almost exclusively the same dry political, military and diplomatic reports that had dominated the

avvisi

.

In this respect the Strasbourg

Relation

set the tone for all the earliest German newspapers. Sticking closely to the model of the manuscript newsletter, the news-sheets adopted none of the features that made news pamphlets attractive to potential purchasers. There were no headlines and no illustrations. There was little exposition or explanation and none of the passionate advocacy or debate that characterised news pamphlets; indeed, there was little editorial comment of any sort. The newspapers also adopted none of the typographical features that helped pamphlet readers find their way through the text. There were no marginalia: in fact the only concession to legibility was an occasional line-break between reports. Although the news-sheets were soon being produced in very considerable numbers – a weekly edition of several hundred was not unusual – they made no allowances for the fact that new readers might not be so well versed in international political affairs as the narrow circle of courtiers and officials who had read the manuscript news-letters.

6

If readers did not know who the Cardinal Pontini recently arrived in Ravenna was (or even the whereabouts of Ravenna), the newsletters made no effort to explain.

For all that the new genre proved exceptionally popular. The Strasbourg

Relation

was joined in 1609 by a second German weekly, the Wolfenbüttel

Aviso

. This did introduce one notable innovation, a title-page, bearing a fine woodcut with a winged Mercury soaring over a landscape populated by busy news-bearers. This gave the Wolfenbüttel paper more of the appearance of a news pamphlet, but greatly reduced the space for news. Since the back of the title-page would also be blank, this left only six pages of an eight-page pamphlet for text. In the Wolfenbüttel case this was probably not crucial, since publication was almost certainly subsidised by the Duke of Wolfenbüttel-Braunschweig, a notable news addict. But this was less suitable for purely commercial ventures, which mostly followed the Strasbourg model of beginning the text immediately below the title-heading. All retained the quarto form familiar from the German news pamphlets and indeed the manuscript newsletters.

The new genre of news publication spread through the German lands very quickly. A weekly paper was established in Basel in 1610, and shortly thereafter in Frankfurt, Berlin and Hamburg. The outbreak of the Thirty Years War in 1618 stimulated a new wave of weekly papers, and a dozen new titles were published after the Swedish invasion of 1630. In the following decade a number of established papers, responding to the quickening of interest in public affairs, began to publish more than one issue in a weekly cycle. Generally these papers appeared two or three times a week, though in 1650 the Leipzig

Einkommende Zeitungen

ventured an issue every weekday. Print runs

also increased rapidly. In 1620 the

Frankfurter Postzeitung

was published in an edition of 450; the Hamburg

Wochentliche Zeitung

may have printed as many as 1,500 copies. This was exceptional; the average print run was probably in the region of 350 to 400.

7

All told we can document the existence of around 200 titles published in Germany by the end of the seventeenth century: a total of some 70,000 surviving issues. Taking into account those that have been lost, this indicates a total output of around 70 million copies. With extraordinary rapidity a large proportion of the literate population of Germany would have had access to this new type of reading, particularly if we consider that these 200 newspapers were spread around eighty different places of publication. In the development of this new market the most significant steps were the establishment of newspapers in the two premier northern commercial centres of Frankfurt and Hamburg. The

Frankfurter Postzeitung

, founded in 1615, was the work of the remarkable Johann von den Birghden, the imperial postmaster.

8

It was von den Birghden who had been responsible for extending the imperial post network into northern and eastern Germany, notably with the establishment of the crucial arterial route between Frankfurt and Hamburg. The newspaper was very much a by-product of this activity. Sadly von den Birghden did not bring to publishing the same conceptual genius and attention to detail that characterised his work with the post roads: his newspaper is as conventional and undistinguished as the other earliest papers. He was, however, the first to call attention to the close connection between the post and the news in the title of his paper. Its contemporary success and wide distribution can be attested by its survival in almost thirty separate libraries and archives.

9

The situation in Hamburg was rather different. This great commercial city in northern Germany was rather remote from the principal news arteries running along the imperial post route from Italy to the Low Countries. Necessarily the city had relied on its own messenger services, established since the medieval period, and by the sixteenth century a regular network of courier services connected the Hanseatic port with trading partners in the Baltic, the Low Countries and England. The founder of the first Hamburg newspaper, Johann Meyer, was heavily involved in the long-distance freight trade. Drawing on the connections developed from this business, Meyer had created a manuscript news service; rather like Carolus in Strasbourg, the establishment of his

Wöchentliche Zeitung auss mehrerley örther

was an attempt to mechanise this existing business. The potential for growth was, however, far greater in Hamburg, a great regional centre of trade and news, and Meyer's venture was very successful. The profits to be made soon sparked controversy with others in the Hamburg book world. In 1630 a consortium of booksellers

and bookbinders challenged Meyer's right to sell the paper directly to his customers. After submissions from both sides the city council determined that Meyer could sell his paper retail for the first three days of the week; thereafter it was to be made available to local booksellers in batches of one hundred for 9 pfennig per copy.

10

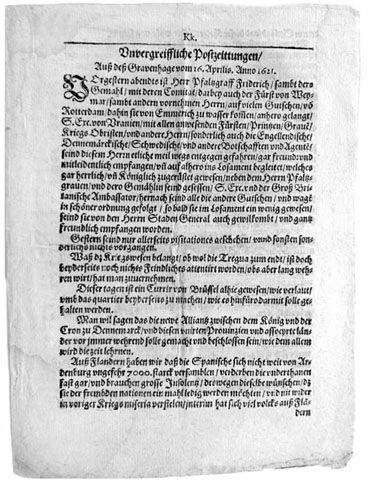

9.1 An early issue of the

Frankfurter Postzeitung

. The newspaper offers a good coverage of news from northern Europe, especially the Low Countries.

Hamburg soon established a role as the supplier of news for the whole of northern Germany; other regional papers were essentially reprints of texts supplied from Hamburg, a fact explicitly acknowledged in the title of the first Rostock paper, the rather confusingly named

Wöchentliche Newe Hambürger Zeitung

.

11

Hamburg was also the first city in Germany where the potential profits of newspaper publishing led to serious rivalry between competing papers. In 1630 Meyer faced not only complaints from the local booksellers

but the emergence of a potentially serious challenge from a new imperial postmaster, Hans Jakob Kleinhaus. This was at the height of imperial military success in the Thirty Years War and in setting up his own paper, the

Postzeitung

, Kleinhaus seemed determined to put Meyer out of business.

12

The dispute rumbled on until Meyer's death in 1634 when his paper was inherited by his redoubtable widow, Ilsabe. Her determination to maintain her livelihood found a sympathetic hearing with the city magistrates. In 1637 the council brokered a settlement. The postmaster's insistent claim to a monopoly of the press in Hamburg was refuted, but his exclusive use of the title

Postzeitung

was upheld. Still, Ilsabe was not yet finished. In this era it was common (and thoroughly inconvenient for students of the press) for proprietors to refresh the name of their papers quite frequently. If they moved to twice-weekly publication they would also often give the mid-week edition a separate title.

13

Ilsabe Meyer took to shadowing the changing title of the imperial paper to blur the distinction between them. When the postmaster renamed his paper the

Priviligierte Ordentliche Post Zeitung

, hers became the

Ordentliche Zeitung

.