The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (27 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

All of these events provoked a profound response from Europe's increasingly anxious and divided peoples, demonstrating the extent to which the various channels of news had now merged and intertwined as the consequences of faraway events became matters of real and present urgency. Those telling the news reflected the strong emotions of their audience: the need to be informed or consoled, the desire for reassurance or the urge for exuberant celebration. This was a new world, in which expanding horizons revealed a sense of more imminent peril.

Lepanto

The battle of Lepanto was the consequence of a clash of cultures that had persisted, without hope of resolution, since the fall of Constantinople in 1453. By extinguishing Byzantium the Ottoman Empire had announced its arrival as the dominant power in the eastern Mediterranean. An inescapable partner in matters of trade, since the Turks now controlled access to the spice market of the Levant, each successive sultan posed a potent challenge to Venetian power in the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas. Meanwhile Turkish armies gradually advanced through the remnants of Byzantine lands in the Balkans to the borders of Habsburg Austria. Print had come just too late to record the fall of Constantinople, but the successive stages of this advance were each marked by a flurry of news pamphlets: the fall of Negroponte in 1470, which coincided with the beginnings of print in Rome and Venice; the siege of Rhodes in 1480; the shattering, calamitous reverse at Mohács in 1526 where the destruction of the Hungarian nobility resulted in the partial occupation of this ancient Christian kingdom, and brought Turkish power into the heart of Europe. All of these events were followed with fascination in Europe's western lands.

2

With the death of Hungary's young king Louis at Mohács, the remnants of the kingdom passed into Habsburg hands; this was welcomed as a bulwark of Europe's defence. Attempts to form a common front brought forth fine exhortations to a new crusade. These events too were widely reported in the news press.

7.1 A broadsheet portrait of Ibrahim Pascha. The fascination with the Turkish Empire was an enduring feature of sixteenth-century news culture.

We have already had occasion to acknowledge Christopher Columbus's letter announcing his New World discoveries as a highly effective and precocious piece of news management.

3

Over the course of the next century Europe's reading public would digest the importance of the explorations and conquest of new continents. So it bears repeating that for contemporaries – and quite distinct from our own historical perception – the interest in the Americas was always dwarfed by the incessant, recurrent fear of Turkish conquest.

4

And so it went on. The siege of Vienna (1529), the capture of Tunis (1535), the disasters at Algiers (1541) and Djerba (1560), all were significant news events. A new chapter opened with the siege of Malta in 1565. Confronting a heroic resistance from the Knights of St John, the sultan's army was eventually forced into retreat. The European news community could follow these events not only in a burst of celebratory pamphlets, but in detailed maps of Malta's

fortifications, progressively updated during the stages of the siege.

5

The relief of Malta proved to be only a temporary respite. Five years later, in 1570, Cyprus was attacked by an overwhelming Turkish force, and despite heroic resistance its Venetian garrison was eventually overcome. This disaster was widely attributed to the failure of the Christian powers to mount an effective relief effort. The Lepanto campaign reflected, at last, a determination to put aside selfish differences, and make common cause. The Christian fleet, sponsored by Venice, Spain and the Pope, set sail eastward on 16 September 1571. The Turkish fleet was discovered in the Gulf of Lepanto on 7 October and battle was joined. Although the forces were fairly evenly matched (208 galleys on the Christian side against 230 in the Turkish fleet), the Holy League's victory was overwhelming.

The arrival of the

Angelo Gabriele

in Venice set off weeks of riotous celebration. Church bells rang out and fireworks were discharged for three days. Mass was celebrated in San Marco by the Spanish ambassador in the presence of the Doge and Senate, followed by a procession headed by the Doge himself carrying the basilica's most precious crucifix. After these official thanksgiving events, different parts of the community, led by the German merchants, staged their own events. These in turn necessitated more feasting, more processions and more fireworks.

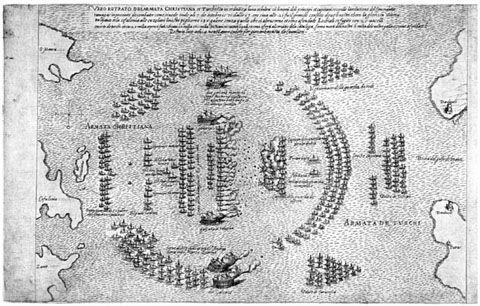

7.2 Engraved Italian depiction of the opposing fleets at Lepanto.

While this was going on, news of the victory was despatched to the capitals of Europe's nation states, carried by couriers and the news writers. The news had reached Lyon by 25 October, and Brussels five days later. A courier from Venice brought the news to Madrid on 31 October. The Venetian ambassador hurried to tell Philip II, and found him in his chapel. When he explained his business he was immediately admitted. ‘The King's joy at receiving the news was extraordinary,’ the ambassador reported with some satisfaction. ‘In that very moment he ordered a Te Deum sung.’

6

The king kept the ambassador by his side for most of the day, and insisted he accompany him at the solemn procession of thanksgiving. The official messenger sent by the fleet commander, Don John, arrived only on 22 November, by this time thoroughly upstaged. Nevertheless, the king questioned him eagerly. The extent to which this news overcame Philip's distaste for meetings (he much preferred written communications) betrays the depths of his joyful relief.

7

Even before the last fireworks had been exploded, the Christian victory had begun to be celebrated in print. In Venice the first wave of pamphlets offered accounts of the celebrations, and were presumably bought as mementos by those who had witnessed or participated in these events.

8

Thereafter such reports turned to reconstructing the heroic tale of victory. Many of these short pamphlets were despatched abroad along with the manuscript

avvisi

: around fifty Venetian editions found their way in this manner into the Fugger archive.

9

A number of the news prints adopted the

avviso

title of the manuscript newsletters, though not all of them adopted the same dispassionate style. The

Aviso to Sultan Selin, of the rout of his fleet and the death of his captains

was not the reproduction of an

avviso

, but a jeering piece of triumphalism.

10

The news narratives were then reinforced by a third wave of publications, celebrating the Christian triumph in verse. The victory inspired an astonishing outburst of creative energy in Italian literary circles, with at least thirty named authors contributing songs or poems.

11

Almost all of these works were published as short, cheap pamphlets: this was a chance to seize the moment and cash in, for both author and publisher.

The newsletters found a substantial echo in the international press. In Paris, Jean Dallier published a newsletter penned in Venice on 19 October, the very day the news of victory had arrived, together with a letter from Charles IX ordering the bishop of Paris to organise an official thanksgiving. Further accounts of the battle were published by four other Paris printers as well as in Lyon and Rouen.

12

The first English pamphlets were translated copies of these Paris imprints.

13

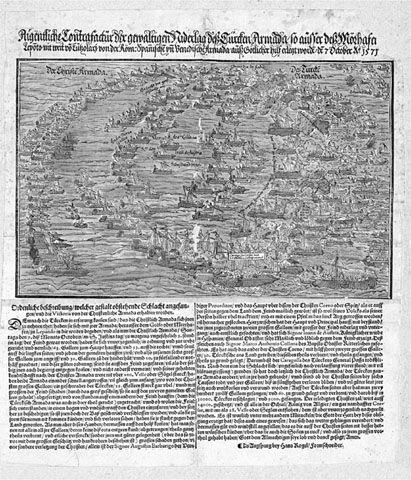

German news pamphlets were published in Augsburg, Vienna and at least five other cities.

14

One enterprising Augsburg printer had a woodcut view of the battle (clearly based on an Italian original) made to accompany a

broadsheet description of the events.

15

German printers also produced their share of celebratory songs, to match those of the Italians. The celebration was heartfelt and generous. Few at this point paused to reflect what might be the consequences of this extraordinary vindication of Spanish military might. This was that rare news event which created, for a fleeting moment, a shared community of celebration that overrode all considerations of partisan advantage. It would not be repeated in the difficult years that followed.

7.3 A German news broadsheet, with an account of the battle of Lepanto. The debt to the Italian model is obvious, though this makes for a more dramatic rendition.

Massacre

The victory of Lepanto represented a rare moment of unity in Europe's divided Christendom. A year later the fragility of this sentiment was laid bare in an event so shocking that it seared the consciousness of Protestant Europe for two centuries. It began with a wedding, intended to reconcile France's feuding religious parties. It ended with over five thousand dead in an unbridled orgy of killing that put beyond hope any prospect of religious reconciliation.

On 22 August 1572 the leader of France's Huguenots, Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, was shot and wounded by a concealed gunman as he rode through Paris. The young king, Charles IX, who was personally close to Coligny, sent guards and his personal physician to attend to the wounded man. It was clear that Coligny would live, but the mood turned ugly as the Protestant nobility, crammed into the city for the marriage of their titular lord, Henry of Navarre, called angrily for retribution. In a heated late-night meeting of the Privy Council the king was persuaded that only a pre-emptive strike could thwart a Protestant insurrection. Early on the morning of 24 August the Catholic champion, the Duke of Guise, was despatched to see to the murder of the injured Coligny. What followed was probably at least partly unintended. As the remains of the admiral's corpse were hauled through the streets, the Catholic nobility, city militia and population of Paris began settling scores. First the noble Huguenot leadership, then other prominent Calvinists and finally ordinary men and women of the congregations were hunted down and killed. News of the massacre sparked copycat events in other French cities: in Lyon, Rouen, Orléans and Bourges. Those who did not die recanted or fled. The Huguenot movement in northern France was effectively destroyed.

16

St Bartholomew's Day, 24 August 1572, was for Protestants a day that would live in infamy; indeed, they ensured that it would, by a carefully nurtured campaign of remembrance that put the piteous human drama at the heart of a tale of treachery, bad faith and deceit.

17

The news of the massacre spread rapidly through Europe. In the Protestant states the reaction was one of stunned disbelief at the scale of the calamity, followed by searing anger and revulsion. The first news of the Parisian massacre reached Geneva, the fountainhead of French Calvinism, on Friday 29 August, brought by merchant travellers from Savoy. The following Sunday, Théodore Beza and his colleagues announced the sombre news in their sermons. Beza, Calvin's successor in Geneva, seems at this point to have been in a state of shock. In a brief letter of 1 September written to his opposite number in Zurich, Heinrich Bullinger, he spoke in apocalyptic terms. Three hundred thousand co-religionists in France stood in imminent danger, as did those sheltering in Geneva: this might, he

warned his friend, be the last time he would be able to write. ‘For it is abundantly clear that these massacres are the unfolding of a universal conspiracy. Assassins are seeking to kill me, and I contemplate death more than life.’

18

This was an exaggeration born of shock and despair. But the fear that the attacks in France heralded a universal conspiracy to settle with Protestantism once and for all spread very quickly in Protestant Europe. On 4 September the Genevan city council, which had acted with admirable speed in sharing the news with Swiss allies, wrote in far more emotional tones to the Count Palatine, a key German friend of the Reformed religion: