The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (12 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

It was swiftly recognised that the labour of inscribing such certificates would be greatly reduced if the terms and details of the gift could be printed, leaving gaps for insertion of the name of the recipient and the sum donated. Certificates of indulgence soon became a ubiquitous feature of publishing in Germany. For printers, this was the ideal commission. The work was short, a few simple lines of text, easily set up and executed. Since the complete text was a single sheet, on one side of paper, it demanded no technical sophistication. Most crucially, a printed indulgence posed the printer none of the complex problems of distribution that shipwrecked so many early businesses. With indulgences the printer undertook the work as a commission from a single client, normally the bishop or a local church. It would be for the institution to distribute the copies: the printer would receive his full payment on delivery of the work.

The scale of this business was clearly immense. Of the 28,000 printed texts that have survived from the fifteenth century, the first age of print, around 2,500 were single-sheet items or broadsheets. Of these, a third were indulgences. Furthermore, indulgence certificates were printed in far larger editions than was normal. The earliest books were printed in editions of around 300, rising to 500 by the end of the fifteenth century. However, for indulgences we know of orders for 5,000, 20,000, even in one case for 200,000 copies.

9

This was work so lucrative that printers would often interrupt or put aside other orders to fulfil these commissions, as frustrated authors frequently complained. Gutenberg was one of many printers who undertook work of this sort, alongside more ambitious projects.

10

This sort of ephemeral printing is particularly prone to the natural wastage that has caused so much early print to be lost. Some publications that have vanished altogether can only be documented from archival records. Taking all this into account, we can reliably estimate that by the end of the fifteenth century printers would have turned out as many as three to four million indulgence certificates. This was good work for printers, and they grabbed it like a lifeline.

The indulgence campaigns also gave rise to a host of associated works. One of Gutenberg's early publications was the so-called

Türkenkalendar

, a six-leaf pamphlet entitled

A Warning to Christendom against the Turks

.

11

Under the guise of a calendar for the year 1455, a series of verses exhort the Pope, Emperor and the German nation to arm for the fight against the common enemy. The following year Pope Calixtus III proclaimed a Bull exhorting the whole of Christendom to join the crusade, either in person or through

monetary contributions. The German translation of this Bull was published as a fourteen-leaf pamphlet.

12

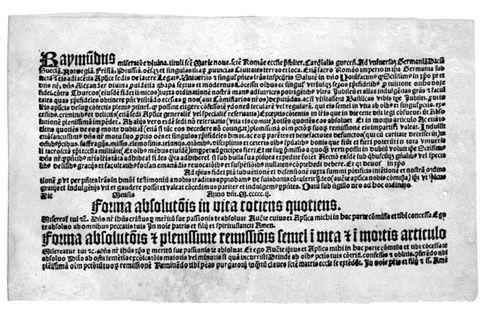

3.1 The trade in salvation. An indulgence published as part of Raymond Peraudi's third great German campaign, 1502.

These pamphlets had an important news function. Campaigns that raised money for international causes, such as the incessant calls for crusade against the encroaching Ottoman Empire, brought news of these faraway events to a wide public.

13

These publications, though generally originating in Italy, achieved a remarkable geographical range. The crusading writings of Cardinal Bessarion were among the first books published in France.

14

William Cousin's account of the siege of Rhodes was the first book published in Scandinavia (in 1480). Two years later, an explanation of the plenary indulgence decreed for the Turkish crusade was the very first book published in the Swedish language.

15

The unchallenged superstar of this new financial evangelism was Cardinal Raymond Peraudi. An indefatigable preacher and pamphleteer, Peraudi led three major fund-raising campaigns in northern Europe between 1488 and 1503. His sermons were major events for the towns that received him, and the sums raised were divided between the Church and the local authorities according to a carefully laid-down formula. Peraudi's activities were supported in a blizzard of publications, in both broadsheet and pamphlet form.

16

The careful orchestration of information, exhortation and excitement has much in common with modern campaigning techniques.

17

Peraudi would arrive in a

city with great pomp and circumstance. His visit was often preceded by publications announcing his impending arrival and the cause for which he preached. After he had roused the crowds to pious devotions, contributors would be provided with the indulgence certificate stipulating their donation and the promised remission. Those keen to learn more could buy locally printed copies of Peraudi's sermon.

Peraudi could not be everywhere, so in other places the campaign was led by appointed deputies. In Sweden it was headed by the Dutchman Anthonius Mast, who brought with him 20,000 letters of indulgence, of which 6,000 were taken on to Finland by Michael Poyaudi.

18

This was a carefully coordinated and highly sophisticated media campaign, designed to energise Christendom to a sense of shared responsibility for critical events in faraway lands. It was also a precocious demonstration of the potential impact of printing.

These events were intensely moving for those who witnessed a great preacher at work; for the history of publishing they are also deeply significant. For many of Europe's citizens the precious certificate of indulgence would be the first printed text they owned. In contrast to the rather conservative instincts of many early publishers, these fund-raising campaigns increased awareness in the industry of the possibilities of the new medium. The publishing opportunities surrounding the preaching of indulgences alerted many publishers for the first time to the value of cheap print. It was an important dry-run for the media storm that would engulf Germany a generation later with the coming of the Reformation.

New Worlds

On 18 February 1493 a small weather-beaten ship, the

Niña

, made landfall on one of the Portuguese islands of the Azores. On board was the Genoese adventurer Christopher Columbus, who had just completed the first successful voyage back and forth across the expanse of the Atlantic Ocean. The discovery of the Americas was one of the critical turning points in world history, and it took place just as Europe's public was beginning to explore the potential of printing as a news medium. In 1492, the same year that Columbus had set sail from Spain, a giant meteor fell near the Alsace village of Ensisheim. An enterprising poet, Sebastian Brant, had composed a verse description of the event. Several German publishers then printed this text, along with a bold woodcut representation of the meteor racing across the sky. This news broadsheet proved enormously popular, and several editions still survive.

19

The discovery of the Americas was potentially of a whole different order. In the long term, if hopes were realised of large discoveries of gold and spices, it

could transform the European economy. In the shorter term it pitted against each other the two great monarchies competing for domination of the trans-oceanic lands, Portugal and Castile-Aragon. A few years later the Portuguese would triumphantly conclude their own momentous feat of exploration, linking the Eastern spice lands with the European market by rounding the southern tip of Africa.

At the time, it must be said, this Portuguese expedition seemed to Europe's news markets the more significant story of the two. The true impact of Columbus's three great voyages emerged only gradually. Despite this, the response to Columbus offers a particularly interesting case study of a developing news event at a time when the news market was itself in a state of transition.

Even before the forced landfall in the Azores, Columbus was acutely aware that accounts of his voyage would have to be carefully managed. He had departed garlanded with the most expansive promises of rewards should he find, as he had promised, a westward passage to the Asian spice markets. As Admiral of the Ocean Seas he and his heirs were to be invested with hereditary dominion and a tenth of the profits emanating from the new discovered lands. His ships had crossed the ocean but what they had discovered was by no means clear. Columbus could not definitely confirm a route to Asia, nor offer any clear prospect of riches: the novelties he could display, parrots and native captives, might seem an insufficient surrogate for the gold and spices he had promised.

Even to make his report to Ferdinand and Isabella, Columbus had first to endure a second unwanted brush with the Portuguese. After extricating his crew, with some difficulty, from the Azores, Columbus's ship was forced to take refuge in the harbour of Lisbon. He was summoned to a potentially difficult interview with the King of Portugal, a man who had previously turned down his offer of service, but would now have a very shrewd understanding of what his navigational feat might mean.

Before he attended this awkward rendezvous, Columbus had taken the precaution of sending a report of his discoveries to his royal patrons at Barcelona. He despatched a second copy from the Spanish port of Palos, near Cadiz, after his patched-up ship had been allowed to sail on – to his enormous relief – from the Portuguese capital. Both reports made their way successfully to Barcelona, where they had in fact already been anticipated by a messenger from Martin Pinzón, captain of the

Pinta

, which had been separated from the Admiral's ship in the storm that blew Columbus into the Azores. The

Pinta

made landfall in northern Spain, from where Pinzón sent word overland to the court, asking leave to come in person to tell the story of the voyage. This was refused: the sovereigns insisted this was the prerogative of Columbus. He

was now summoned to Barcelona for what became a triumphant festival of celebration.

In the weeks following Columbus's meeting with Ferdinand and Isabella, further manuscript copies of his report circulated around the court. It was not long before one appeared in print, in a Spanish translation published in Barcelona. A copy of the original letter was printed almost simultaneously in Valladolid, and it was this Latin

Epistola de insulis nuper inventis

('Letter from the islands recently discovered') that became the basis for a rapid flurry of reprints: in Rome, and north of the Alps at Basel, Paris and Antwerp. A paraphrase of this letter was also rendered into Italian by Giuliano Dati, and it too found an eager public, with three editions published before the end of the year.

20

Columbus, for all his fantasies and delusions, was a remarkable man. He had charted, almost by instinct, what was to prove the most expeditious route for transatlantic sailing; he also proved a remarkably effective publicist. His account of this first voyage was a masterpiece of concise exposition, fitting neatly into an eight-page pamphlet. But the commercial success of

De insulis inventis

should not lead us to overestimate its influence in shaping contemporary perceptions of Columbus's discoveries. Even before the pamphlet was printed in Rome, sometime after 29 April 1493, news of the voyage had already made its way to at least seven different cities through manuscript reports.

21

These manuscript letters, and the earliest verbal reports, seem to be what weighed most heavily among opinion-formers. Columbus stuck doggedly to the view, at least in public, that the lands he had discovered were Asiatic; he had therefore fulfilled the terms of his contract and deserved his reward. Others were more sceptical. Among those who had the chance to converse with Columbus at court were two men who would themselves be influential in promoting the oceanic discoveries in their publications, Pietro Martire d'Anghiera and the young Bartolomé de Las Casas. At his Lisbon landfall Columbus had also made the acquaintance of Bartholomeu Dias, a veteran of the first Portuguese voyages around the Cape. These men were aware that Columbus had done something remarkable, but doubted that he had found a route to Asia. The formal response of his royal patrons reflected this emerging consensus: their greeting referred more ambiguously to ‘Islands you have discovered in the Indies’.

Such doubts did not diminish enthusiasm for Columbus's announced plan for a return voyage. He had little difficulty in recruiting 1,500 volunteers, who in September 1493 embarked with a greatly enhanced fleet of seventeen ships. But the stakes were very high. The potential of the westward voyages pointed up the need for urgent resolution of the contesting claims of Spain and Portugal. News of an agreement, the treaty of Tordesillas, was conveyed to

Columbus in a letter from Queen Isabella in 1494 when he was already back in Hispaniola. The fact that other ships were already at this stage making the Atlantic passage independently also caused Columbus problems. It was now more difficult to manage news: reports of the increasingly chaotic state of the new settlements were soon being conveyed back to Spain by the disgruntled and the disillusioned. The scale of royal investment in the second and third voyages made the dawning recognition that Columbus's Asian fantasy had no foundation difficult to deal with. On his return in late 1496 from his second voyage, Columbus was subjected to a formal commission of inquiry; during the third voyage he was stripped of his powers and returned to Spain in 1500 in chains.