The Coming Plague (128 page)

Authors: Laurie Garrett

44

J. K. Todd, M. Ressman, S. A. Caston, et al., “Corticosteroid Therapy for Patients with Toxic Shock Syndrome,”

Journal of the American Medical Association

252 (1984): 3399â3402.

Journal of the American Medical Association

252 (1984): 3399â3402.

45

L. K. Altman, “Bacteria Are Linked to Deadly Childhood Disease,”

New York Times,

December, 3, 1993: A28.

New York Times,

December, 3, 1993: A28.

46

A. L. Bisno, “Staphylococcal Endocarditis and Bacteremia,”

Hospital Practice

, April 15, 1986: 139â58.

Hospital Practice

, April 15, 1986: 139â58.

47

D. Y. M. Leung, H. C. Meissner, D. R. Fulton, et al., “Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin-Secreting

Staphylococcus aureus

in Kawasaki Syndrome,”

Lancet

342 (1993): 1385â88.

Staphylococcus aureus

in Kawasaki Syndrome,”

Lancet

342 (1993): 1385â88.

48

J. M. Musser, P. Schlievert, A. W. Chow, et al., “A Single Clone of

Staphylococcus aureus

Causes the Majority of Cases of Toxic Shock Syndrome,”

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

87 (1990): 225â29.

Staphylococcus aureus

Causes the Majority of Cases of Toxic Shock Syndrome,”

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

87 (1990): 225â29.

49

TSST-1 can stimulate rapid proliferation of T cells in doses of less than 10

-9

M, which means a person could have virtually undetectable amounts of the toxin in his or her blood and develop acute Toxic Shock Syndrome.

-9

M, which means a person could have virtually undetectable amounts of the toxin in his or her blood and develop acute Toxic Shock Syndrome.

50

For a succinct description of the immune system effects of TSST-1, see A. K. Abbas, A. H. Lichtman, and J. S. Pober,

Cellular and Molecular Immunology

(Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1991), 304.

Cellular and Molecular Immunology

(Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1991), 304.

51

B. N. Kreiswirth, J. S. Kornblum, and R. P. Novick, “Genotypic Variability of the Toxic Shock Syndrome Exoprotein Determinant,” in J. Jeljaszewicz, ed.,

The Staphylococci

(Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag, 1985).

The Staphylococci

(Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag, 1985).

52

M. C. Chu, B. N. Kreiswirth, P. A. Pattee, et al., “Association of Toxic Shock Toxin-1 Determinant with a Heterologous Insertion of Multiple Loci in the

Staphylococcus aureus

Chromosome,”

Infection and Immunity

56 (1988): 2702â8.

Staphylococcus aureus

Chromosome,”

Infection and Immunity

56 (1988): 2702â8.

53

Plasmids were self-contained units of DNA that could be exchanged from one microbe to another either as random events, or in response to specific survival pressure when a population of bacteria were exposed to antibiotics. For further details of both the TSST-1 and penicillin-resistance transposons, see: Murphy, E. “Transposable Elements in Gram-Positive Bacteria.” Chapter 9. Eds. D. E. Berg and M. M. Howe.

Mobile DNA

. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology, 1989.

Mobile DNA

. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology, 1989.

13. The Revenge of the Germs

1

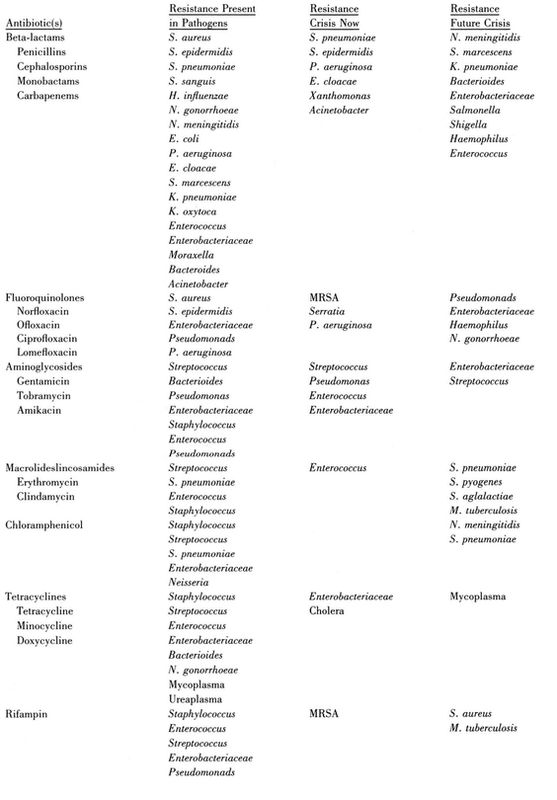

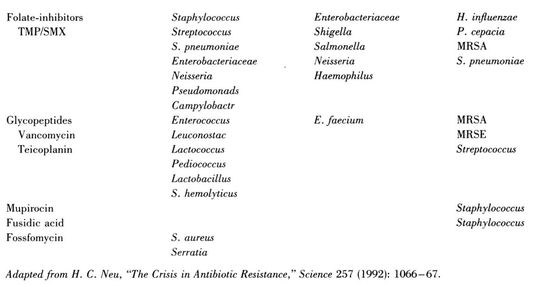

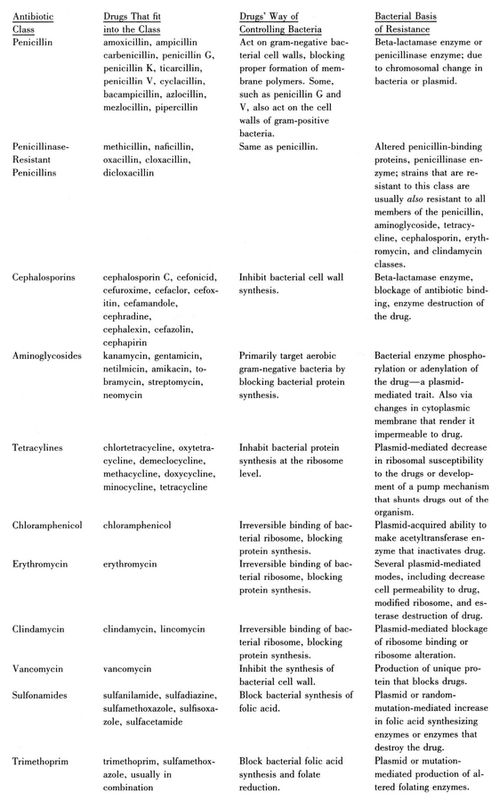

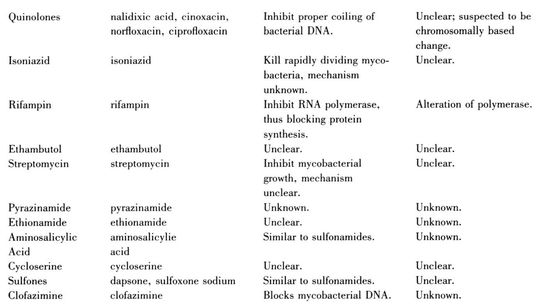

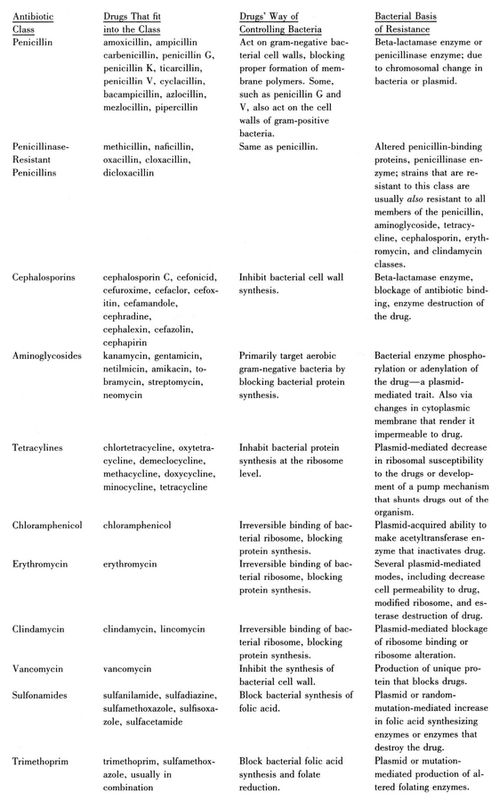

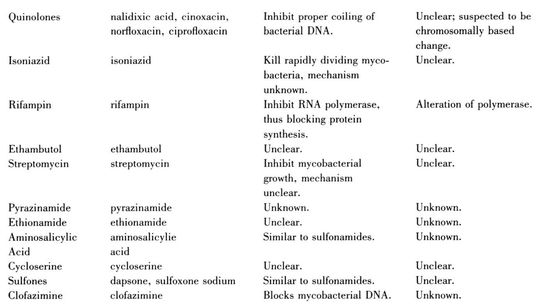

There are thousands of natural and synthetic antibiotics, relatively few of which have been tested and marketed. The most commonly used are as follows:

2

A. L. Bisno, “Staphylococcal Endocarditis and Bacteremia,”

Hospital Practice

, April 15, 1986: 139â58.

Hospital Practice

, April 15, 1986: 139â58.

3

A. L. Panililo, D. H. Culver, R. P. Gaynes, et al., “Methicillin-Resistant

Staphylococcus aureus

in U.S. Hospitals, 1975â1991,”

Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology

13 (1992): 582â86.

Staphylococcus aureus

in U.S. Hospitals, 1975â1991,”

Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology

13 (1992): 582â86.

4

M. Truneh, “Phage Types and Drug Susceptibility Patterns of

Staphylococcus aureus

from Two Hospitals in Northwest Ethiopia,”

Ethiopian Medical Journal

29 (1991): 1â6.

Staphylococcus aureus

from Two Hospitals in Northwest Ethiopia,”

Ethiopian Medical Journal

29 (1991): 1â6.

5

E. E. Udo and W. B. Grubb, “Transfer of Resistance Determinants from a Multi-Resistant

Staphylococcus aureus

Isolate,”

Journal of Medical Microbiology

35 (1990): 72â79.

Staphylococcus aureus

Isolate,”

Journal of Medical Microbiology

35 (1990): 72â79.

6

For overviews of the antibiotic resistance crisis, see M. L. Cohen, “Epidemiology of Drug Resistance: Implications for a Post-Antimicrobial Era,”

Science

257 (1992): 1050â55; S. M. Finegold, “Antimicrobial Therapy of Anaerobic Infections: A Status Report,”

Hospital Practice,

October 1979: 71â81; L. O. Gentry, “Bacterial Resistance,”

Orthopedic Clinics of North America

22 (1991): 379â88; A. Gibbons, “Exploring New Strategies to Fight Drug-Resistant Microbes,”

Science

257 (1992): 1036â38; M. Lappe,

Germs That Won't Die

(Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1982); S. B. Levy,

The Antibiotic Paradox

(New York: Plenum Press, 1992); H. C. Neu, “The Crisis in Antibiotic Resistance,”

Science

257 (1992): 1064â73; Panlilio et al. (1992), op. cit.; and M. Toner, “When Bugs Fight Back,” Pulitzer Prize-winning series of reports in the

Atlanta Constitution

, August 23, 1992âOctober 16, 1992.

Science

257 (1992): 1050â55; S. M. Finegold, “Antimicrobial Therapy of Anaerobic Infections: A Status Report,”

Hospital Practice,

October 1979: 71â81; L. O. Gentry, “Bacterial Resistance,”

Orthopedic Clinics of North America

22 (1991): 379â88; A. Gibbons, “Exploring New Strategies to Fight Drug-Resistant Microbes,”

Science

257 (1992): 1036â38; M. Lappe,

Germs That Won't Die

(Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1982); S. B. Levy,

The Antibiotic Paradox

(New York: Plenum Press, 1992); H. C. Neu, “The Crisis in Antibiotic Resistance,”

Science

257 (1992): 1064â73; Panlilio et al. (1992), op. cit.; and M. Toner, “When Bugs Fight Back,” Pulitzer Prize-winning series of reports in the

Atlanta Constitution

, August 23, 1992âOctober 16, 1992.

7

D. P. Levine, B. S. Fromm, and B. R. Reddy, “Slow Response to Vancomycin or Vancomycin Plus Rifampin in Methicillin-Resistant

Staphylococcus aureus

Endocarditis,”

Annals of Internal Medicine

115 (1991): 674â80.

Staphylococcus aureus

Endocarditis,”

Annals of Internal Medicine

115 (1991): 674â80.

8

D. S. Kernodle and A. B. Kaiser, “Comparative Prophylactic Efficacy of Cefazolin and Vancomycin in a Guinea Pig Model of

Staphylococcus aureus

Wound Infection,”

Journal of Infectious Diseases

168 (1993): 152â57; and R. P. Wenzel, “Preoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis,”

New England Journal of Medicine

326 (1992): 337â39.

Staphylococcus aureus

Wound Infection,”

Journal of Infectious Diseases

168 (1993): 152â57; and R. P. Wenzel, “Preoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis,”

New England Journal of Medicine

326 (1992): 337â39.

In Denmark, where national medical registries are excellent because all the nation's citizens receive their health care from the federal government, a review of the country's meningitis cases from 1986 to 1989 revealed that 104 people had suffered the severe ailment as a result of staphylococcal infection. Sixty-one of the cases were acquired in the hospital following surgery. Fortunately, none of the Danish cases was MRSA, but all involved some degree of penicillin resistance. See A. G. Jensen, F. Esperson, P. Skinhøj, et al.,

“Staphylococcus aureus

Meningitis,”

Archives of Internal Medicine

153 (1993): 1902â8.

“Staphylococcus aureus

Meningitis,”

Archives of Internal Medicine

153 (1993): 1902â8.

9

Bacterial subtypes 29/52/80/95 in Detroit; 29/77/83A/85 in Boston. See L. R. Crane, D. P. Levine, M. J. Zervos, and G. Cummings, “Bacteremia in Narcotic Addicts at the Detroit Medical Center: I. Microbiology, Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Empiric Therapy,”

Review of Infectious Diseases

8 (1986): 364â73; and D. E. Craven, A. I. Rixinger, T. A. Goularte, and W. R. McCabe, “Methicillin-Resistant

Staphylococcus aureus

Bacteremia Linked to Intravenous Drug Abusers Using a âShooting Gallery,'”

American Journal of Medicine

80 (1986): 770â76.

Review of Infectious Diseases

8 (1986): 364â73; and D. E. Craven, A. I. Rixinger, T. A. Goularte, and W. R. McCabe, “Methicillin-Resistant

Staphylococcus aureus

Bacteremia Linked to Intravenous Drug Abusers Using a âShooting Gallery,'”

American Journal of Medicine

80 (1986): 770â76.

10

Udo and Grubb (1990), op. cit.

11

B. Kreiswirth, J. Kornblum, R. D. Arbeit, et al., “Evidence for a Clonal Origin of Methicillin Resistance in

Staphylococcus aureus,” Science

259 (1993): 227â30.

Staphylococcus aureus,” Science

259 (1993): 227â30.

12

For an overview of the global penicillin resistance trends, for example, see C. C. Sanders and W. E. Sanders, Jr., “Beta-Lactam Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria: Global Trends and Clinical Impact,”

Clinical Infectious Diseases

15 (1992): 824â39.

Clinical Infectious Diseases

15 (1992): 824â39.

14

Cohen (1992), op. cit.

15

C. E. Phelps, “Bug/Drug Resistance: Sometimes Less Is More,”

Medical Care

27 (1989): 194â203.

Medical Care

27 (1989): 194â203.

16

D. L. Stevens, M. H. Tanner, J. Winship, et al., “Severe Group A Streptococcal Infections Associated with a Toxic Shock-like Syndrome and Scarlet Fever Toxin,”

New England Journal of Medicine

321 (1989): 1â7.

New England Journal of Medicine

321 (1989): 1â7.

17

K. Wright, “Bad News Bacteria,”

Science

249 (1990): 22â24.

Science

249 (1990): 22â24.

18

H. C. Dillon, and C. W. Derrick, Jr., “Streptococcal Complications: The Outlook for Prevention,”

Hospital Practice

, September 1972: 93â101.

Hospital Practice

, September 1972: 93â101.

19

S. P. Gotoff, “Emergence of Group B Streptococci as Major Perinatal Pathogens,”

Hospital Practice

, September 1977: 85â90.

Hospital Practice

, September 1977: 85â90.

20

Neu (1992), op. cit.

21

Centers for Disease Control, “Prevalence of Penicillin-Resistant

Streptococcus pneumoniae

âConnecticut, 1992â1993,”

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

43 (1994): 216â23.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

âConnecticut, 1992â1993,”

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

43 (1994): 216â23.

22

A survey of 748 cardiac patients treated in Johannesburg, South Africaâall of whom were poor blacks who had suffered childhood bouts of rheumatic feverâillustrated the severity of heart disease produced by the bacteria. Under the apartheid state, black South Africans lived in conditions of acute squalor and health care deprivation. As a result, during the 1980s rheumatic fever was about as common among black South Africans as it had been among white urban Americans in 1920. And like their 1920s counterparts in the United States, black South Africans who survived rheumatic fever during early childhood had a better than 50 percent chance of facing life-threatening heart disease before their twentieth birthday. The primary cause of their cardiac difficulties was mitral valve damage which required open-heart surgery. R. H. Marcus, P. Sareli, W. A. Pocock, and J. B. Barlow, “The Spectrum of Severe Rheumatic Mitral Valve Disease in a Developing Country,”

Annals of Internal Medicine

120 (1994): 177â83.

Annals of Internal Medicine

120 (1994): 177â83.

Dealing surgically with rheumatic fever heart damage has been likened to “attempting to mop up the water on the floor while leaving the faucet open,” particularly in the context of poor countries. WHO during the 1990s instituted a trial program of rheumatic fever prevention in sixteen developing countries that involved training local paramedics to recognize streptococcal throat infections in children and treat the kids prophylactically with benzathine penicillin to prevent recurrent infections. M. J. McLaren, M. Markowitz, and M. A. Gerber, “Rheumatic Heart Disease in Developing Countries: The Consequence of Inadequate Prevention,”

Annals of Internal Medicine

120 (1994): 243â44.

Annals of Internal Medicine

120 (1994): 243â44.

23

L. G. Veasy, S. E. Wiedneier, G. S. Orsmond, et al., “Resurgence of Acute Rheumatic Fever in the Intermountain Area of the United States,”

New England Journal of Medicine

316 (1987): 421â27.

New England Journal of Medicine

316 (1987): 421â27.

24

See “Streptococcal Diseases,” in A. S. Benenson, ed.,

Control of Communicable Diseases in Man

(Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association, 1990), 411â18.

Control of Communicable Diseases in Man

(Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association, 1990), 411â18.

25

L. A. Haglund, G. R. Istre, D. A. Pickett, et al., “Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in Central Oklahoma: Emergence of High-Level Penicillin Resistance and Multiple Antibiotic Resistance,”

Journal of Infectious Diseases

168 (1993): 1532â35.

Journal of Infectious Diseases

168 (1993): 1532â35.

26

F. Shan, S. Germer, and D. Hazell, “Aetiology of Pneumonia in Children in Goroka Hospital, Papua New Guinea,”

Lancet

II (1981): 537â41.

Lancet

II (1981): 537â41.

27

World Health Organization, “Implementation of the Global Strategy for Health for All by the Year 2000, Second Evaluation; and Eighth Report on the World Health Situation,” report to the 45th World Health Assembly, Provisional Agenda Item 17, Geneva, 1992.

28

J. S. Spika, M. H. Munshi, B. Wojtyniak, et al., “Acute Lower Respiratory Infections: A Major Cause of Death in Children in Bangladesh,”

Annals of Tropical Pediatrics

9 (1989): 33â39; and B. J. Selwyn and BOSTID, “The Epidemiology of Acute Respiratory Tract Infection in Young Children: Comparison of Findings from Several Developing Countries,”

Review of Infectious Diseases

12 (1990): S870âS888.

Annals of Tropical Pediatrics

9 (1989): 33â39; and B. J. Selwyn and BOSTID, “The Epidemiology of Acute Respiratory Tract Infection in Young Children: Comparison of Findings from Several Developing Countries,”

Review of Infectious Diseases

12 (1990): S870âS888.

29

World Health Organization, “Acute Respiratory Infections in Children: Case Management in Small Hospitals in Developing Countries,” Program for the Control of Acute Respiratory Infections, Geneva, 1990.

Other books

Die For You by A. Sangrey Black

Angelmonster by Veronica Bennett

Skunked! by Jacqueline Kelly

The Haunting Ballad by Michael Nethercott

Dazzling Danny by Jean Ure

The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot by Robert Macfarlane

Cattle Valley 28 - Second Chances by Carol Lynne

Besotted by le Carre, Georgia

03. Masters of Flux and Anchor by Jack L Chalker

The Queen of the Tearling by Erika Johansen