The Coming Plague (126 page)

Authors: Laurie Garrett

183

L. Chakrabarti, M. Guyader, M. Alizon, et al., “Sequence of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus from Macaque and Its Relationship to Other Human Simian Retroviruses,”

Nature

328 (1987): 543â47.

Nature

328 (1987): 543â47.

184

Marx (1987), op. cit.

Essex, working in collaboration with Gallo's lab and researchers from Sweden's Karolinska Institute and the Universite Pierre et Marie Curie in Paris, reached a similar conclusion about the viruses' similarity. See S. K. Arya, B. Beaver, L. Jagodzinski, et al., “New Human and Simian HIV-related Retroviruses Possess Functional Transactivator (tat) Gene,”

Nature

328 (1987): 548â50. But they stressed that it was possible that they were looking at an example of cross-species transmission of the same virus, from monkey to man.

Nature

328 (1987): 548â50. But they stressed that it was possible that they were looking at an example of cross-species transmission of the same virus, from monkey to man.

Harking back to disputes a decade earlier between Gallo and Japanese researchers over credit for discovery of HTLV-I, Yorio Hinuma of the Cancer Institute in Tokyo had isolated an SIV virus from wild-caught African green monkeys in 1985. His team, which had been instrumental in earlier HTLV-I efforts, now was credited with discovery of SIVagm, given evidence that Essex's group was studying an SIVmac contaminant.

185

Y. Ohta, T. Masuda, H. Tsujimoto, et al., “Isolation of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus from

African Green Monkeys and Seroepidemiologic Survey of the Virus in Various Nonhuman Primates,”

International Journal of Cancer

41 (1988): 115â22.

African Green Monkeys and Seroepidemiologic Survey of the Virus in Various Nonhuman Primates,”

International Journal of Cancer

41 (1988): 115â22.

186

Fukasawa, M. Miura, T. Hasegawa, A., et al. “Sequence of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus from African Green Monkey, A New Member of the HIV/SIV Group,”

Nature

33 (1988): 457â461.

Nature

33 (1988): 457â461.

187

For good reviews of these findings, see R. C. Desrosiers, “A Finger on the Missing Link,”

Nature

345 (1990): 326; M. McClure, “AIDS and the Monkey Puzzle,”

New Scientist

, March 25, 1989; and M. McClure, “Where Did the AIDS Virus Come From?”

New Scientist

, June 30, 1990: 54â57.

Nature

345 (1990): 326; M. McClure, “AIDS and the Monkey Puzzle,”

New Scientist

, March 25, 1989; and M. McClure, “Where Did the AIDS Virus Come From?”

New Scientist

, June 30, 1990: 54â57.

188

R. F. Khabbaz, W. Heneine, J. R. George, et al., “Brief Report: Infection of a Laboratory Worker with Simian Immunodeficiency Virus,”

New England Journal of Medicine

330 (1994): 172â77.

New England Journal of Medicine

330 (1994): 172â77.

189

F. Gao, L. Yue, A. T. White, et al., “Human Infection by Genetically Diverse SIVsm-related HIV-2 in West Africa,”

Nature

358 (1992): 495â99.

Nature

358 (1992): 495â99.

190

R. Nowak, “HIV-2 and SIV May Be the Same Virus,”

Journal of NIH Research

4 (1992): 38â40.

Journal of NIH Research

4 (1992): 38â40.

191

C. Rouzioux, G. Jaeger, F. Brun-Vézinet, et al., “Absence of Antibody to LAV/HTLV-III and STLV-III (mac) in Pygmies,” II International Conference on AIDS, Paris, June 23â25, 1986.

192

It would constitute a major breakthrough in AIDS research when University of Washington at Seattle scientists succeeded in infecting

Macaca nemestrina

monkeys with HIV-1, producing immune deficiency and lymphoma in the animals. From the earliest stages of the AIDS epidemic scientists had been infecting chimpanzees with HIV-1, but the animals never developed AIDS.

Macaca nemestrina

monkeys with HIV-1, producing immune deficiency and lymphoma in the animals. From the earliest stages of the AIDS epidemic scientists had been infecting chimpanzees with HIV-1, but the animals never developed AIDS.

193

U. Dietrich, M. Adamski, H. Kühnel, et al., “A Highly Divergent HIV-2 Related Strain, HIV-2alt, Defines an Alternative Subtype of the HIV-2/SIV mac/SIVsm Group of Primate Immunodeficiency Viruses,” IX International Conference on AIDS, Berlin, June 6â11, 1993.

194

S. Giunta and G. Groppa, “The Primate Trade and the Origin of AIDS Viruses,”

Nature

329 (1987): 22; and A. Karpas, “Origin and Spread of AIDS,”

Nature

348 (1990): 578.

Nature

329 (1987): 22; and A. Karpas, “Origin and Spread of AIDS,”

Nature

348 (1990): 578.

195

T. Huet, R. Cheynier, A. Meyerhans, et al., “Genetic Organization of a Chimpanzee Lentivirus Related to HIV-1,”

Nature

345 (1990): 356â58.

Nature

345 (1990): 356â58.

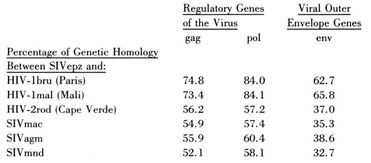

The details were presented as follows:

This showed that over two-thirds of the chimpanzee viral genes and HIV-1 were the same, versus far less commonality between SIVcpz and the other simian viruses or HIV-2.

196

J. N. Nkengasong, M. Peeters, B. Willems, et al., “Phenotypic and Antigenic Properties of HIV-1 Isolates from Cameroon,” I International Conference on Human Retroviruses and Related Infections, Washington, D.C., December 12â16, 1993.

197

G. Myers, K. Maclnnes, and L. Myers, “Phylogenetic Moments in the AIDS Epidemic,” Chapter 12 in S. S. Morse, ed.,

Emerging Viruses

(Oxford, Eng.: Oxford University Press, 1993).

Emerging Viruses

(Oxford, Eng.: Oxford University Press, 1993).

198

There are about 9,700 nucleotides, or discrete bits of genetic information, inside an HIV virus. Nobel laureate Howard Temin (co-discoverer of reverse transcriptase and retroviruses) estimated that HIV-1 mutates at the rate of 2 Ã 10

-2

substitutions per nucleotide per year. Put another way, if one could follow all the nucleotides in a population of HIV-1âassuming that the viruses were all identical at the outsetâa year later there would be about fifty mutated nucleotides in any given virus one examined. And the whole population of viruses, which had been uniform at the outset, would have over the course of a year undergone thousands of generations of replication, becoming a heterogeneous swarm of dozens of quasispecies. An annual mutation rate of 2 Ã 10

-2

was one of the highest seen in any viral species; but the cow virus responsible for foot-and-mouth disease mutated at a rate of 3 Ã 10

-2

and the segment of the influenza virus responsible for its ability to infect human cells was an even more rapid mutator. See H. M. Temin, “Is HIV Unique or Merely Different?”

Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes

2 (1989): 1â9.

-2

substitutions per nucleotide per year. Put another way, if one could follow all the nucleotides in a population of HIV-1âassuming that the viruses were all identical at the outsetâa year later there would be about fifty mutated nucleotides in any given virus one examined. And the whole population of viruses, which had been uniform at the outset, would have over the course of a year undergone thousands of generations of replication, becoming a heterogeneous swarm of dozens of quasispecies. An annual mutation rate of 2 Ã 10

-2

was one of the highest seen in any viral species; but the cow virus responsible for foot-and-mouth disease mutated at a rate of 3 Ã 10

-2

and the segment of the influenza virus responsible for its ability to infect human cells was an even more rapid mutator. See H. M. Temin, “Is HIV Unique or Merely Different?”

Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes

2 (1989): 1â9.

A study of the earliest HIV-1 strains found in people in 1983â85 similarly revealed a mutation rate

of between 0.4 and 1.6 percent per year. The highest mutation rates occurred in viruses that were cultured repeatedly in the laboratory, undoubtedly subjected to selection pressures and contamination that wouldn't occur naturally. Nevertheless, a median 1 percent annual metamorphosis rate seemed reasonable for wild HIV-1 viruses. See P. C. Sheng-Yung, B. H. Bowman, J. B. Weiss, et al., “The Origin of HIV-1 Isolate HTLV-IIIB,”

Nature

363 (1993): 466â69.

of between 0.4 and 1.6 percent per year. The highest mutation rates occurred in viruses that were cultured repeatedly in the laboratory, undoubtedly subjected to selection pressures and contamination that wouldn't occur naturally. Nevertheless, a median 1 percent annual metamorphosis rate seemed reasonable for wild HIV-1 viruses. See P. C. Sheng-Yung, B. H. Bowman, J. B. Weiss, et al., “The Origin of HIV-1 Isolate HTLV-IIIB,”

Nature

363 (1993): 466â69.

199

M. A. McClure, M. S. Johnson, D. F. Feng, and R. F. Doolittle, “Sequence Comparisons of Retroviral Proteins: Relative Rates of Change and General Phylogeny,”

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

85 (1988): 2469â73.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

85 (1988): 2469â73.

200

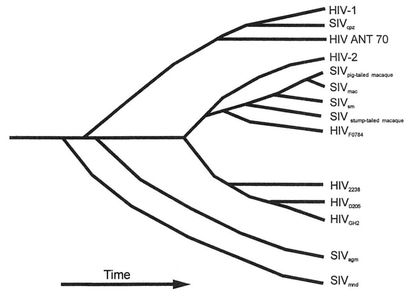

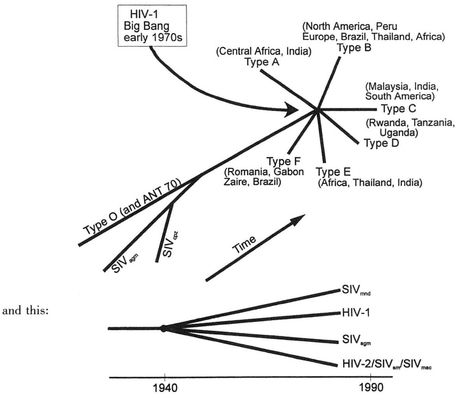

There are several ways to picture these historical arguments. Paul Ewald, of Amherst College in Massachusetts, sees AIDS viral evolution as follows:

Source: P. W. Ewald, “AIDS: Where Did It Come From and Where Is It Going?” in

Evolution of Infectious Diseases

(Oxford, Eng.: Oxford University Press, 1993), chapter 8.

Evolution of Infectious Diseases

(Oxford, Eng.: Oxford University Press, 1993), chapter 8.

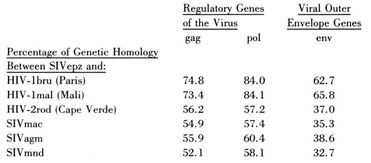

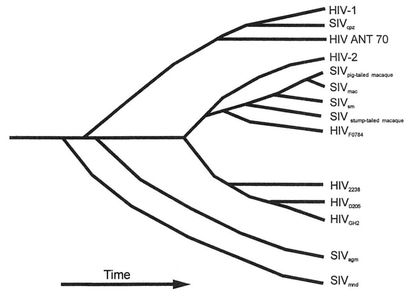

Gerald Myers pictured the evolution more like this:

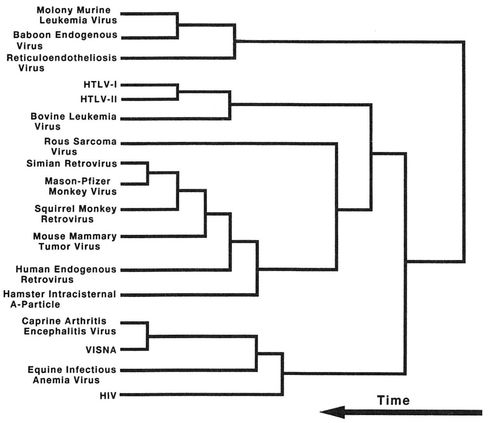

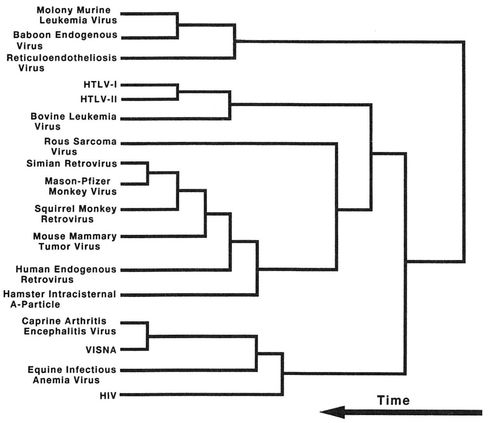

On a larger evolutionary scale, comparing HIV to other similar viruses, Doolittle saw this:

201

The experience of Marburg disease, as described in earlier chapters, left many scientists wondering just how safe monkey-derived vaccines might be.

202

See P. Brown, “US Rethinks Link Between Polio Vaccine and HIV,”

New Scientist

, April 4, 1992: 10; T. Curtis, “The Origin of AIDS,”

Rolling Stone

625 (1992): 54â106; T. Curtis and P. Manson, “Do Cold, Hard AIDS Facts Lie in Freezer? Researchers Look for Clues in Old Vials of Polio Vaccine,”

Houston Post

, April 16, 1992: Al; C. H. Fox, “Possible Origins of AIDS,”

Science

256 (1992): 1259â60; A. J. Garrett, A. Dunham, and D. J. Wood, “Retroviruses and Poliovaccines,”

Lancet

342 (1993): 932â33; Giunta and Groppa (1987), op. cit.; “In the Beginning,”

The Economist

, March 14, 1992: 99â100; W. S. Kyle, “Simian Retroviruses, Poliovaccine and Origin of AIDS,”

Lancet

339 (1992): 600â1; G. Lecatsas and J. J. Alexander, “Origins of HIV,”

Lancet

339 (1992): 1427; A. McGregor, “Poliovaccine and AIDS Origin Link Very Unlikely,”

Lancet

340 (1992): 1090â91; “Panel Nixes Congo Trials and AIDS Source,”

Science

258 (1992): 304â5; and T. F. Schulz, “Origin of AIDS,”

Lancet

339 (1992): 867.

Rolling Stone

later printed an apologia: “âOrigin of AIDS' Update,” December 9, 1992: 40.

New Scientist

, April 4, 1992: 10; T. Curtis, “The Origin of AIDS,”

Rolling Stone

625 (1992): 54â106; T. Curtis and P. Manson, “Do Cold, Hard AIDS Facts Lie in Freezer? Researchers Look for Clues in Old Vials of Polio Vaccine,”

Houston Post

, April 16, 1992: Al; C. H. Fox, “Possible Origins of AIDS,”

Science

256 (1992): 1259â60; A. J. Garrett, A. Dunham, and D. J. Wood, “Retroviruses and Poliovaccines,”

Lancet

342 (1993): 932â33; Giunta and Groppa (1987), op. cit.; “In the Beginning,”

The Economist

, March 14, 1992: 99â100; W. S. Kyle, “Simian Retroviruses, Poliovaccine and Origin of AIDS,”

Lancet

339 (1992): 600â1; G. Lecatsas and J. J. Alexander, “Origins of HIV,”

Lancet

339 (1992): 1427; A. McGregor, “Poliovaccine and AIDS Origin Link Very Unlikely,”

Lancet

340 (1992): 1090â91; “Panel Nixes Congo Trials and AIDS Source,”

Science

258 (1992): 304â5; and T. F. Schulz, “Origin of AIDS,”

Lancet

339 (1992): 867.

Rolling Stone

later printed an apologia: “âOrigin of AIDS' Update,” December 9, 1992: 40.

203

N. Touchette, “Fact or Fiction? HIV and Polio Vaccines,”

Journal of NIH Research

4 (1992): 40â41.

Journal of NIH Research

4 (1992): 40â41.

204

See J. Rifkin, letter to Dr. James Mason, Director, CDC. undated, 1987; P. M. Boffey, “Cattle Virus Tied to AIDS,”

New York Times

, July 7, 1987: Al; J. Rifkin, letter to Dr. Frank Young, Commissioner, Food and Drug Administration, August 3, 1987; and J. B. Wyngaarden and B. W. Hawkins, letter to Mr. Jeremy Rifkin, Foundation on Economic Trends, September 23, 1987.

New York Times

, July 7, 1987: Al; J. Rifkin, letter to Dr. Frank Young, Commissioner, Food and Drug Administration, August 3, 1987; and J. B. Wyngaarden and B. W. Hawkins, letter to Mr. Jeremy Rifkin, Foundation on Economic Trends, September 23, 1987.

Other books

Out of Aces by Stephanie Guerra

CLAIMED (By the Alpha Billionaire #2) by St. James, Rossi

Running Stupid: (Mystery Series) by James Kipling

His Dakota Bride (Book 5 - Dakota Hearts) by Mondello, Lisa

Two Miserable Presidents by Steve Sheinkin

Voices (Whisper Trilogy Book 3) by Michael Bray

Non-Stop Till Tokyo by KJ Charles

Seducing Her Beast by Sam Crescent

RAGE (Descendants Saga (Crisis Sequence One)) by Somers, James