Resident Readiness General Surgery (48 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

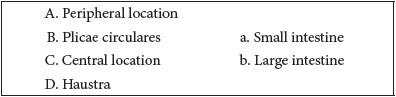

Figure 37-2.

The same supine film as presented in the case. Note the dilated loops of small bowel as well as what appears to be fluid between the small bowel walls. (Reproduced, with permission, from Doherty GM.

Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery

. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010.)

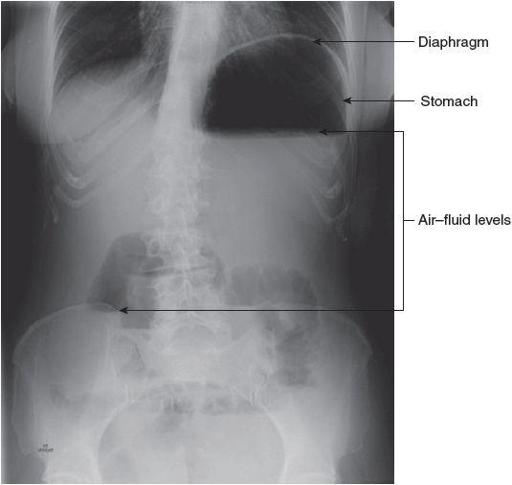

Figure 37-3

, in contrast, is an upright film that shows air–fluid levels. You should note the very large gastric air bubble and the paucity of colonic air (normally seen deep in the pelvis, below the pelvic brim). Both of these elements suggest an obstruction. If you know approximately where the small and large bowels lie within the abdomen, the pattern of air–fluid levels can also suggest the location of the obstruction. For example, in the case of a small bowel obstruction, multiple air–fluid levels may be seen involving the small intestine only, whereas a large bowel obstruction may present with air–fluid levels within both the small and large intestines.

Figure 37-3.

Upright film shows a distended stomach with a large gastric bubble. It also shows slightly dilated loops of small bowel with air–fluid levels and a paucity of colonic gas, both consistent with a small bowel obstruction. (Courtesy of Deborah Levine, MD.)

2.

On a KUB, the small and large intestines are most easily distinguished from each other on the basis of position, diameter, mucosal markings, and gas patterns. As previously mentioned, the small intestine tends to lie within the midabdomen and has a normal diameter of less than 3 cm, whereas the colon usually courses along the periphery and is normally less than 6 cm in diameter. In terms of bowel markings, the circular mucosal folds (plicae circulares or valvulae conniventes) of the small bowel span the entire circumference of the wall. They are also closer in proximity to each other than are the haustra of the large intestine, which appear to cross only part of the large intestinal lumen (see

Figure 37-2

).

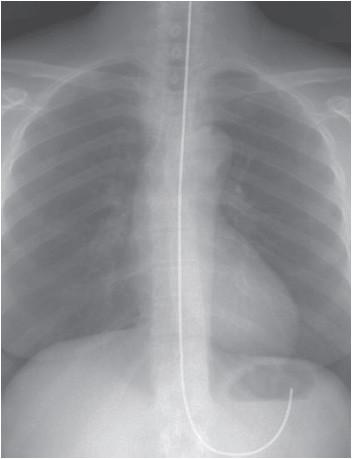

3.

Using a KUB, one can follow the entire gastrointestinal course of an NGT and ensure its proper positioning beneath the left hemidiaphragm and well within the lumen of the stomach (see

Figure 37-4

).

Figure 37-4.

A feeding tube located below the diaphragm—note that in this image the tube is postpyloric. (Reproduced, with permission, from McKean SC, Ross JJ, Dressler DD, Brotman DJ, Ginsberg JS, eds.

Principles and Practice of Hospital Medicine

. Figure 119-4.)

Postplacement imaging with a KUB can ensure that the tube is not erroneously placed within the patient’s airway or that it ends too proximally within the esophagus.

4.

The presence of extraluminal intraperitoneal gas or a pneumoperitoneum is a worrisome finding on a KUB and usually warrants emergent surgical intervention. Note that some extraluminal gas is to be expected after open and laparoscopic surgery, although it typically resolves over a period of 3 to 6 days and is not accompanied by concerning physical exam findings. The most common place to look for extraluminal gas is underneath the diaphragm. Because air is less dense than the intra-abdominal contents, it tends to rise, so extraluminal gas is most easily visualized on an erect or upright film. Note that it’s best to look for air underneath the right hemidiaphragm as it may be difficult to distinguish

the extraluminal air due to a perforation from the gastric air bubble on the left. Other potential locations for extraluminal gas include the bowel wall (pneumatosis intestinalis, which creates a “bubble wrap” appearance), the portal venous system (usually as a result of severe bowel ischemia), and within the biliary tree (usually following instrumentation or as a result of a biliary-enteric fistula).

TIPS TO REMEMBER

Always take a systematic approach when interpreting a KUB.

Dilated loops of bowel, a prominent gastric bubble or dilated stomach, air–fluid levels, and a paucity of colonic gas all suggest an obstructive process (either ileus or a mechanical obstruction).

When trying to determine if bowel is dilated or not, remember the “3/6/9 rule” (small bowel, colon, cecum).

The small and large intestines can be discriminated from each other by position (small intestine—central, large intestine—peripheral) and bowel markings (small intestine—markings span the

entire

wall circumference, large intestine—markings span only

part

of the wall circumference).

Except in the acute postoperative period, the presence of free extraluminal intraperitoneal air usually warrants emergent intervention.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

Which radiographic finding would most likely require emergent abdominal exploration?

A. Cecum dilated to 8 cm

B. Air–fluid levels within the small intestine

C. Air underneath the right hemidiaphragm

D. Radiopaque densities in the RUQ

2.

Match each term with its radiographic characteristic:

Answers

1.

C

. Air underneath the right hemidiaphragm is an abnormal radiographic finding that suggests an intra-abdominal perforation, warranting emergent abdominal exploration. The upper limit of normal for cecal diameter is 9 cm, air–fluid levels within the small intestine suggest a bowel obstruction (which can often be treated nonoperatively), and radiopaque densities in the RUQ likely represent gallstones.

2.

A and D—b

. The colon tends to lie in a peripheral location within the abdomen and has haustra (bowel markings that cross only part of the intestinal lumen).

B and C—a

. The small bowel is identified radiographically by its central position in the abdomen and by the plicae circulares that span the entire circumference of the small intestinal wall.

A 30-year-old Woman With Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

A 30-year-old Woman With Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting