Resident Readiness General Surgery (69 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

3.

For the reasons noted in question #1, the relationship between the resident and patient must always be seen in the broader context of the relationship between the attending surgeon and the patient. For the reasons noted in question #2 above, the discussion between resident and attending surgeon about sensitive issues such as what is in the patient’s best interests should be done in private. You must not forget that your ability to effectively function as part of the surgical team and render good patient care is predicated on your ability not only to be proactive in rendering patient care but also to ensure ongoing communication and understanding between you and your attending supervisor, and the other health care professionals on the team.

4.

No one should be expected to carry out what he or she perceives as an immoral or unethical action, no matter what “orders” might have been given. Certainly, in a situation such as described above, a difference of opinion about what a patient “would have wanted” is often so subjective that it would not normally be the sort of major issue for which a resident would withdraw from participating in the patient’s care. However, when faced with a clear and significant breach of ethics (eg, if the resident were to feel that going along with the attending surgeon would lead to significant harm to the patient), then the resident should respectfully withdraw from the patient’s care. Furthermore, if a resident perceives any health care provider is a danger to the patient or himself or herself, the resident should report it to the program director or other trusted individual positioned in an educational leadership role.

TIPS TO REMEMBER

The attending surgeon and patient established a relationship prior to the resident–patient relationship. Therefore, resident concerns or disagreements in patient care should be communicated in private to the attending.

If a resident has a major moral conflict with some aspect of a patient’s care that cannot be resolved even after communicating with an attending, the resident should respectfully withdraw from the patient’s care.

Residents should communicate concerns or ethical conflicts with their program director, a trusted mentor, or other member of the educational leadership team.

A 35-year-old Man Who Is Disruptive on the Floor

A 35-year-old Man Who Is Disruptive on the Floor

Xavier Jimenez, MD and

Shamim H. Nejad, MD

Mr. Downey is a 35-year-old gentleman with a history of heroin dependence, alcohol abuse, and cocaine abuse, transferred from the county jail and admitted for observation after deliberately ingesting a razor blade in order to prevent being transferred to prison. He had a similar episode two months prior to this admission in which the razor blade was removed via EGD in the emergency room. On this presentation, however, he declined an EGD, demanding instead that he be operated upon. As there was no indication of an acute abdomen, he was instead admitted for observation with the plan for him to pass the razor blade on his own, and to surgically intervene only if he developed signs of peritonitis or perforation. In the emergency department, all vitals and laboratory results are unremarkable. The patient’s last use of heroin, alcohol, and cocaine was approximately six months ago, prior to his incarceration.

On admission, the patient is accompanied by two guards and is shackled at all times. On the floor he begins demanding clonazepam for the treatment of his anxiety disorder and hydromorphone intravenously for acute pain complaints. His affect ranges from irritable to angry to bouts of tearfulness. He intermittently swears at nursing staff as well as at you and your senior resident. Whenever his requests are denied or perceived to not be met, he begins to kick his bedside stand, yell, or bang his head on the bed or the floor until he is restrained by his guards and hospital security. On the second hospital day, an abdominal KUB shows the presence of not only the razor blade but also two batteries that the patient apparently ingested from the television remote in his room. When asked why he ingested the batteries, the patient again states his fear of returning to jail and his strong desire to avoid going back to prison “at all costs.” He then blames the surgical team for not treating his pain and anxiety causing him to “act out,” and threatens that if “no one listens” to him, he will do it again.

1.

What diagnoses might this patient have that would explain this behavior?

2.

What communication techniques would you use in approaching this patient?

DIFFICULT PATIENTS

All patients bring aspects of themselves into clinical encounters—and so do you. A distinction can be made between healthy or adaptive traits and dysfunctional or maladaptive traits.

Adaptive traits

include sound judgment, adequate frustration tolerance, delayed gratification, an ability to cooperate, and emotional control, whereas Mr. Downey exhibits a number of

maladaptive traits

. He experiences

emotion dysregulation, moving quickly from irritability to anger to sadness. He also shows low frustration tolerance and an inability to delay gratification, as evidenced by his outbursts when not given what he requests. In addition, he overtly attacks and devalues members of the clinical team, with little, if any, regard for their concerns. His history of polysubstance dependence and requests for numerous medications also suggest generally poor coping mechanisms for managing stress or pain. Globally, Mr. Downey lacks impulse control, sound judgment, and insight into his maladaptive traits.

Clinicians also carry aspects of their own identities and personalities into clinical encounters, and at times they can feel strong emotional reactions to their patients. This is particularly the case in difficult patients, especially those who devalue others or malinger symptoms. As such, Mr. Downey likely inspires negative feelings in clinicians involved with him, including discomfort, fear, anxiety, or anger. This can lead to avoidance or neglect of the patient by the clinician, contributing further to the patient’s emotional and behavioral outbursts, which in turn leads to ever-more clinician resentment. In an effort to break this cycle, it is important to identify these reactions, and to discuss them openly with team members and supervisors.

Psychiatry can be consulted to assist in management with difficult patients. For instance, certain symptoms may be amenable to pharmacological management. Mr. Downey exhibits a labile mood and poor impulse control, suggesting the possible role for a dopamine antagonist if his outbursts cannot be otherwise managed. In the event of severe agitation or violence, patients may benefit from a dopa-mine antagonist as needed for behavioral control. This may reduce the incidence of agitation and violence along with decreasing the need for physical restraints. Benzodiazepines may need to be used in conjunction with dopamine antagonists to control extrapyramidal side effects and to potentiate the antipsychotic’s effect, but must be used with caution in any patient with a history of substance abuse, as Mr. Downey has. Ultimately, very close or constant observation may be necessary in order to prevent further ingestion of items that will prolong his stay. This is particularly important as a patient improves medically and surgically as disposition out of a structured setting, such as a hospital, causes some patients to regress psychologically with resulting behavioral dysregulation. Other indications for consulting psychiatry include instances in which a patient may lack the capacity to accept or refuse treatments based on poor judgment or insight, as well as general breakdowns in communication or cooperation with the treatment team.

Answers

1.

It is important to rule out any conditions (medical and psychiatric) that contribute to maladaptive expressions or behaviors. This includes mood disorders (eg, bipolar illness), anxiety disorders (eg, PTSD), psychotic disorders, delirium, factitious disorder, malingering, or substance-induced states. When traits appear in

the absence of other conditions and are pervasive, fixed, and severely maladaptive, it is important to seriously consider a personality disorder, although generally it requires a longitudinal history of this behavior before labeling a difficult patient with this kind of diagnosis. Personality disorders must be diagnosed with caution, as once a patient is labeled as such, it may make it difficult for the surgical team to treat the patient objectively without their own emotions interfering.

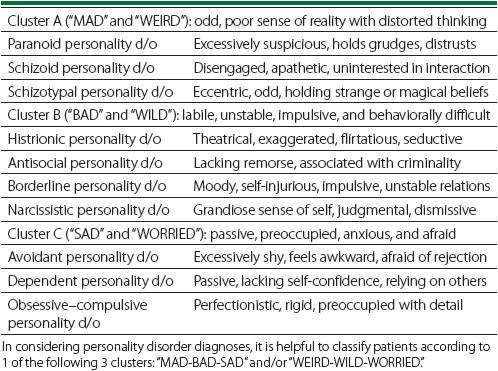

Table 54-1

describes the various personality disorders. Mr. Downey has normal laboratory values and vitals, has not recently used mood-altering substances, is otherwise physically healthy, and has been admitted in the past for similar reasons. He very well might, therefore, have a personality disorder. However, he is clearly attempting to obtain secondary gain (remaining out of prison) by his behavior, and so malingering would be high on the differential list in this case too.

Table 54-1.

Personality Disorder Diagnoses

Given his maladaptive traits (lack of remorse for others, poor impulse control, emotional dysregulation, limited coping, etc), a history of incarceration, and the deliberate creation of medical problems with specific aims, Mr. Downey most likely is demonstrating malingering. He may also fit within Cluster “B” pathology and may fit the diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder.