Resident Readiness General Surgery (47 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

When using pharmacotherapy, labetalol and nitroglycerin are good choices for patients with underlying CAD.

Be careful using nitroglycerin in patients who are preload dependent (ie, hypovolemia, aortic stenosis).

As a general guideline, aim to reduce the blood pressure by approximately 15% in the first hour of therapy. Aim to reduce the blood pressure by no more than 25% over several hours.

Hydralazine—while used frequently by interns/residents—can be injurious to patients with CAD, and the onset and duration of its effects are hard to predict.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

Which of the following comorbidities (one or more) would concern you most about a patient’s ability to tolerate acute postoperative HTN?

A. Emphysema/COPD

B. CAD

C. Systolic heart failure

D. Hypothyroidism

2.

Of the following, which is the most important to assess in a patient with acute postoperative HTN?

A. Neurologic symptoms

B. Home medication list

C. Urinary retention

D. Pain control

3.

Which medication would be appropriate to use in a hypertensive patient who you think is hypovolemic and has a known history of CAD?

A. Labetalol

B. Nitroglycerin

C. Hydralazine

Answers

1.

B and C

. A patient with CAD is at risk of demand ischemia due to the increased afterload. A patient with heart failure may not be able to maintain his/her already tenuous cardiac output with increased afterload.

2.

A

. While it is important to assess for treatable/reversible factors prior to pharmacotherapy, you must always first assess a patient’s vital signs and whether he/she is experiencing symptoms of end-organ damage (ie, neurologic, cardiac, etc).

3.

A

. Labetalol is good for CAD and does not decrease preload, which is already low in a hypovolemic patient.

A 65-year-old Female Who Is 4 Days Postoperative With Nausea, Vomiting, and a Distended Abdomen

A 65-year-old Female Who Is 4 Days Postoperative With Nausea, Vomiting, and a Distended Abdomen

Ashley Hardy, MD and Marie Crandall, MD, MPH

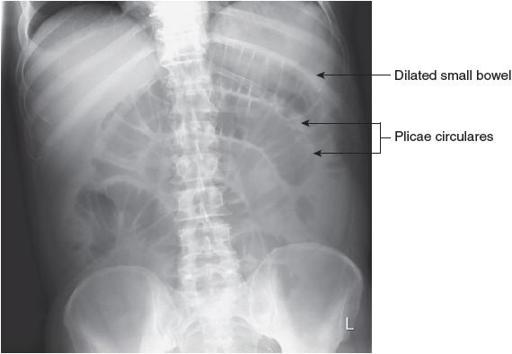

You are called to the surgical floor to evaluate a 65-year-old female who underwent a right hemicolectomy for colon cancer four days prior. For the last few hours the patient has had multiple episodes of nausea with vomiting and has yet to have flatus or a bowel movement since her procedure. Her vital signs are normal, her abdominal exam is notable only for distension, and labs obtained earlier that morning are unremarkable. Of note, the patient is still requiring use of her morphine PCA for postoperative analgesia. You order a KUB, as seen in

Figure 37-1

.

Figure 37-1.

Small bowel obstruction. Supine film showing dilated loops of small bowel and no gas in the colon. (Reproduced, with permission, from Doherty GM.

Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery

. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010. Figure 29-5.)

1.

For this patient, name two key findings you should be looking for on the KUB.

2.

How can you distinguish the small intestine from the colon on a KUB?

3.

Given the patient’s nausea and vomiting, you elect to place a nasogastric tube (NGT). What radiographic landmarks would you use to ensure the tube is properly positioned?

4.

What findings on a KUB would warrant emergent surgical intervention?

READING AND USING A KUB

Answers

1.

Although they stand for kidneys, ureters, and bladder, KUBs are more commonly utilized to assess for abnormal conditions of the gastrointestinal tract and to determine the position of various indwelling devices, including NGTs, Dobhoff (feeding) tubes, and ureteral stents. In a patient such as this one, with a history of recent abdominal surgery and several bouts of nausea and vomiting, it is important to assess for the presence of obstruction or evidence of anastomotic breakdown (as indicated by the presence of free intraperitoneal air). A KUB is quick, relatively inexpensive, and has a lower radiation dose than CT, making it a common initial diagnostic study.

When encountering any type of film, including a KUB, it is important to take a systematic approach to interpretation. Doing so ensures that key findings pertinent to making appropriate decisions regarding a patient’s care are not missed. If previous films are available, it is helpful to compare the findings with those of the current study. After ensuring that you’re viewing the film for the correct patient, determine the orientation (right vs left as indicated by a marker or using the gastric air bubble in the LUQ as a guide). Also determine

if you’re looking at a film that was obtained while the patient was supine versus erect as this will influence whether or not you’re able to visualize the presence of air–fluid levels and free air under the diaphragm. Keep in mind that on plain radiographs high-density structures (generally those that contain calcium such as bone, gallstones, and kidney stones) are white. Similarly, soft tissue and fluid are light gray, while gas is black.

After orienting yourself to the image, be sure to look for the presence of extraluminal air. Then, turn your focus to the hollow organs. First try to locate the stomach within the LUQ. Note that its visibility is influenced by the presence or absence of gastric air and whether or not the film is erect versus supine—in a supine film the meniscus between the gas bubble and gastric contents will not be visible.

Next, locate the small intestine and the colon. You should assess the entire bowel for evidence of intestinal dilation, keeping in mind the “3/6/9 rule”: the accepted upper limit of normal for the diameter of small bowel is 3 cm, for the colon 6 cm, and for the cecum 9 cm. Dilation of the small or large bowel usually represents either a functional obstruction (ileus) or a mechanical obstruction. The image in the case (

Figure 37-2

, copied from

Figure 37-1

again here, with labels) is an excellent example of a KUB that demonstrates the uniform dilation of the small bowel often seen with either type of obstruction. Note there are no cutoff points or “coffee bean”–shaped loops of bowel that could represent a closed loop obstruction, something that would require immediate operative

intervention. Furthermore, note that because it is supine, there are no air–fluid levels, although the boundaries between the loops of bowel are prominent and likely represent intra-abdominal fluid.