Resident Readiness General Surgery (42 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

Finally, Lindenaur et al retrospectively correlated cardiovascular events and in-hospital mortality with in-hospital β-blockers—another huge 663, 969-surgical-patient study in which β-blockers clearly benefited high-risk patients. Most low-risk patients were not on a β-blocker on hospital admission. This low-risk group did not receive a β-blocker until subsequent to their cardiovascular event, at which time they were statistically included in the β-blocker group. In fairness, this jaw-dropping experimental design flaw was emphasized in a companion editorial. From the flurry of studies examining perioperative β-blockade, several conclusions are permissible:

•

Perioperative myocardial infarction, and probably death, is reduced by judicious use of low-dose, short-acting β-blockers (target a preoperative heart rate of 70 and a postoperative heart rate of 80).

•

If your patient is on β-blockers on admission, do not stop them perioperatively.

•

If your patient should have been on β-blockers preoperatively (ie, the patient had an indication such as hypertension, vascular disease, diabetes, etc), then start them as soon as possible.

•

Overdosing any drug is bad, and overdosing long-acting β-blockers is associated with bradycardia, hypotension, CVA, and death.

2.

You can figure this out by memorizing a single conversion. Note that both of these are the lowest doses normally used for each of these formulations:

TIPS TO REMEMBER

β-Blocker–naïve patients should be written for low-dose, short-acting β-blockers (ie, metoprolol 5 mg IV q6h with hold parameters).

Continue any preoperative β-blockers (with appropriate conversion to IV as needed).

Start low-dose β-blockers in those patients who should have been on them in the first place.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

Do low-dose β-blockers reduce mortality?

A. No, because they increase the rate of strokes.

B. Unsure, the evidence is contradictory.

C. Yes, because they reduce the risk of myocardial infarction.

2.

What should you write for a patient on metoprolol 25 mg PO BID at home?

A. No β-blockade

B. 5 mg IV q6h

C. 5 mg IV q12h

D. 10 mg IV q6h

E. 10 mg IV q12h

F. 12.5 mg IV q6h

G. 25 mg IV q12h

3.

What should you write for a 65-year-old patient who is not on β-blockers at home and just underwent a right hemicolectomy?

A. No β-blockade

B. Metoprolol 5 mg IV q6h

C. Metoprolol 10 mg IV q6h

D. Metoprolol 10 mg IV q12h

Answers

1.

C

. The evidence suggests that low-dose β-blockers do indeed reduce the rates of MI and consequently of death. While the POISE trial showed an increase in mortality, the investigators in that study used doses of β-blocker that are higher than what is recommended.

2.

D

. Remember 12.5 mg PO BID equals 5 mg IV q6h, so twice that is 10 mg IV q6h.

3.

B

. This β-blocker–naïve patient should be given β-blockade only at the lowest dose, that is, at 5 mg IV q6h, and targeting a HR of less than 80. You should also be careful to write appropriate hold parameters (ie, HOLD for HR <60 or SBP <100).

SUGGESTED READINGS

Lindenaur PK, Pekow P, Wang K, Mamidi DK, Gutierrez B, Benjamin EM. Perioperative beta-blocker therapy and mortality after major noncardiac surgery.

N Engl J Med

. 2005;353:349.

Mangano DT, Layug EL, Wallace A, Tateo I. Effect of atenolol on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity after noncardiac surgery. Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group.

N Engl J Med

. 1996;335:1713.

POISE Study Group, Devereaux PJ, Yang H, et al. Effects of extended-release metoprolol succinate in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery (POISE trial): a randomised controlled trial.

Lancet

. 2008;371:1839.

Poldermans D, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. The effect of bisoprolol on perioperative mortality and myocardial infarction in high-risk patients undergoing vascular surgery. Dutch Echocardio-graphic Cardiac Risk Evaluation Applying Stress Echocardiography Study Group.

N Engl J Med

. 1999;341:1789.

A 65-year-old Man Who Is in Respiratory Distress 3 Days Postoperatively

A 65-year-old Man Who Is in Respiratory Distress 3 Days Postoperatively

Jahan Mohebali, MD

Mr. Jones is a 65-year-old man with a history of smoking, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and poorly controlled hypertension. He underwent an uncomplicated Whipple procedure 3 days ago and was transferred to the floor from the surgical ICU this morning. You are the night-float intern, and shortly after receiving sign-out, the nurse pages you to the patient’s bedside stating that she is concerned about how he is doing. On arrival, you find him sitting up in bed and leaning forward. He states that he feels a bit anxious and is having trouble catching his breath. You ask the nurse to obtain a pulse oximetry reading that demonstrates an O

2

saturation of 88%. He is in obvious respiratory distress. You call for an EKG and CXR and proceed with your physical exam.

1.

What are the two most likely causes of this patient’s acute decompensated heart failure?

2.

Which findings in the patient’s preoperative evaluation might suggest that he would be at increased risk of postoperative CHF?

3.

What are typical physical exam findings seen in acute decompensated heart failure?

4.

What laboratory and radiographic studies would be useful for confirming a diagnosis of heart failure and determining the underlying etiology?

5.

What are the first two steps in managing acute postoperative heart failure?

ACUTE POSTOPERATIVE HEART FAILURE

Answers

1.

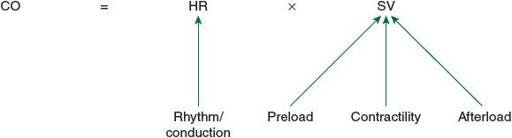

Like many other things in surgery and medicine, one of the best approaches to understanding and managing a clinical condition is to go back to the underlying physiology and basic science. In heart failure, one must think about the pathophysiology of cardiogenic shock that is essentially the result of inadequate cardiac output. Cardiac output is the product of stroke volume and heart rate. While heart rate is essentially dependent on autonomic tone and underlying rhythm, stroke volume is more complex and affected by preload, afterload, and contractility. In certain situations, rhythm may affect preload. Most causes of postoperative heart failure can be attributed to a problem or imbalance in one or more of these factors (see

Figure 34-1

).

Figure 34-1.

The relationship between the various parameters of cardiac output.

Preload

: This should be thought of as the amount of volume in the heart at the end of diastole, right before the heart contracts. In the case of postoperative heart failure, too much preload can overdistend the myocardium and push cardiac function to the far end of the Starling curve (see

Figure 34-2

). The most common cause of this is overly aggressive fluid resuscitation in the immediate postoperative period. Often, patients undergoing large operations will have a postoperative systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) response that will result in third spacing of fluid. This fluid tends to “mobilize” back into the vascular space around postoperative day 3 resulting in sudden intravascular fluid overload. Rhythm can also affect preload. This is discussed separately in the section below.