Hetty Feather (14 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

All the girls looked up expectantly, Sheila clearly

anxious. I wanted to get her into trouble with Nurse

Winterson. But I still did not want it made plain

to all that she had got the better of me. I held my

tongue a second time.

'I tripped and Matron took me off to put this

purple stinging stuff on my chin,' I said.

'It is gentian violet, Hetty. I dare say it hurt a

great deal. You have been very brave, dear.'

I thought the girls might groan to see me singled

out so favourably, but they nodded at me, almost in

a friendly fashion. I did not know then that I had

avoided the worst sin of all at the Foundling Hospital.

No matter how a child is teased or tortured, they

must never ever ever tell a nurse or matron. If they

do, the others will torment them until their last day

at the hospital.

I had unwittingly kept to this rule and won

everyone's respect. I sat and stitched demurely, while

Nurse Winterson read us a story. I loved stories, and

this was a splendid fairy tale – but for once I could

not concentrate.

My mind was whirling. I knew how to reach the

boys' wing, but I would be spotted immediately if I

went back there, unless . . . Unless I could find some

way of disguising myself.

I did not see how this was possible, until later in

the day, when Harriet sought me out.

'Poor Hetty! Look at your sore chin. Oh dear, oh

dear,' she said, making a great fuss of me.

I rather enjoyed this, and even managed to

squeeze out a few tears so she could pet me. She

took me to the big girls' room and sat me close by

her side while she started sewing. She took a pair

of boys' trousers from the big basket and started

patching a knee. I stared at the trousers on her

lap – and smiled. I knew how to obtain the perfect

disguise!

I waited until Harriet had to go to a cupboard

for more thread, peered round quickly, then seized

another pair of trousers from the brimming basket. I

could not be seen carrying them so I thrust them up

my skirts, wedging them in a bunch as best I could.

I positively waddled on my way back to my

dormitory, but I managed to deposit the trousers

safely in my mattress.

The next day I purloined a jacket – and I was

ready! I decided my best chance of reaching the

boys' wing undetected was during the playtime after

dinner. There were fewer nurses on duty, many of

them dining themselves. I stood in the playground

awaiting my opportunity. The other girls took no

notice of me. Sheila seemed disconcerted that I had

not told tales on her, and left me alone.

I hesitated, standing near the girls' entrance,

suddenly in a funk, frightened of being caught and

whipped. I made myself think hard of Gideon. I

pictured him so clearly that he seemed to be standing

before me, white and trembling, tears running

down his face, his mouth opening and shutting

soundlessly. It was such a sad image, it galvanized

me into action.

I gave one last glance to check I was unobserved,

and then I ran into the entrance and up the stairs,

all the way to the dormitory. I tore off my cap and

tippet and apron. I struggled out of my scratchy

brown dress. Then I pulled my stolen jacket and

trousers out of my mattress and put them on. The

trousers were too large and much too long, but I

rolled each leg up at the hem until they rested on

my boots. The jacket was too big too, but it was easy

enough to shrug it up on my shoulders. My shorn

hair suited my purpose well. I had no mirror, but

looking down I could see I appeared a convincing

boy, though I was on the short side. I clenched my

fists and tapped myself on the chest.

'Courage, Hetty,' I whispered.

I hastened out of the dormitory, hating the

heaviness of the jacket on my shoulders, the chafing

of the trousers on my skinny legs. I sped along the

corridor, but then heard the squeak of a nurse's

boots marching along the polished floor.

If she caught me in boys' apparel, all would be

lost. I darted into the girls' washrooms and hid

behind the door, trembling.

Squeak squeak squeak

came the boots, louder now. They paused at the door

of the washrooms. A head poked in and peered, but

I was crammed right back into the corner and she

didn't see me. She went marching on her way, while

I breathed out at last. Once she was out of earshot

I peeped anxiously out of the doorway, and then

resumed my journey.

I turned to the right until I found the boys'

washrooms, and then I carried on down the corridor

until I reached the stairs. I ran down them, but

there at the bottom, right by the door, stood a nurse

watching the boys playing outside. I stopped still,

pressing back into the shadows. I could not bear

to be thwarted now, when I was so nearly there.

I waited, willing her to move, and eventually she

yawned and stretched and sauntered off.

I hurtled out into the playground, blinking at the

sight of so many small boys in brown. They were

so lively too. We girls wandered aimlessly up and

down, or talked in tiny groups, or played decorous

clapping games. These boys were all running and

capering and kicking stones and shouting – all but

one. A spindly boy with a stark haircut stood all

by himself, his head bowed, his hands weirdly splayed as

if he were searching for something that wasn't there.

'Gideon!'

I called.

He looked up and I ran over to him. He cowered

away as if I was going to hit him.

'It's me, Gideon! It's Hetty, your own sister!' I

cried.

He peered at my shorn hair and breeches, looking

doubtful.

'It's really me. Oh, Gideon, I've missed you so!'

I embraced him, my arms tight around his neck.

I felt him crumple, his head on my shoulders, and

then he started sobbing.

'Oh, Gid, it's so hateful hateful hateful, isn't it? If

only we could be together it wouldn't be too bad.'

He straightened up and looked at me imploringly.

'I can't stay, Gideon. The nurses would see I'm

not a real boy – especially when I went to the privy!' I

giggled – and Gideon smiled through his tears. 'How

has it been for you, Gid? Have they been horrid to

you, the other boys?'

Gideon hung his head.

'What about Saul? He's here, isn't he? Does he

look out for you, stand up for you?'

Gideon hunched up further. Saul was clearly not

a protector.

'Well, you must fight back. If you cry, it will only

make them worse. The other girls are hateful to me,

but I punch them and pull their hair and stamp on

their feet until they scream,' I said, exaggerating

fiercely. 'You must do the same.'

Gideon stared at me. We both knew this was a

ridiculous suggestion.

'Try,

Gideon. And you must

say

things. They will

think you are stupid if you won't talk. They will call

you bad names like Idiot Boy.'

Gideon flinched.

'But you're not an idiot, you're clever, just like

me. You can talk perfectly, you just

won't.

Please

say something to me now, Gid.'

Gideon shook his head helplessly.

'For my sake – because you stopped talking when

you got lost in the woods that night I went to the

circus, remember?'

It was clear from Gideon's eyes that he did.

'I've felt so bad since, knowing it was all my fault.

It would make me feel

so

much better if you said

something. Anything. You can call me names if you

like. You can say, "Hetty Feather is a mean, nasty,

pigface, smellybottom sister!" Go on, say it!'

Gideon resisted, but he smiled again.

'Well, say it in your head if you won't say it out

loud. Talk to yourself every day. Talk about

home.

We mustn't forget, Gideon. It's the most important

thing of all. Martha can barely remember anything,

not even me! But if we talk to ourselves and picture

home again and again and again, it will stay true in

our heads. We must picture Mother—'

Gideon moaned softly.

'Yes, remember Mother, her dear red face,

her lovely warm smell, her big chest, our mother.

And great Father, remember him galloping around

with you on his shoulders. And Nat with his jokes

and his whittling. Did they take your wooden

elephant, Gid? They took my dear rag baby. But I've

still got Jem's sixpence safe. Oh, Gideon, picture

Jem, remember our dearest brother, and listen to

me, listen hard: Jem is going to come for me when

I'm older, and he'll come for you too, and we'll

all live together and be happy again – and you

will be free to dance, Gid. You can even wear a silver

suit if you like. Remember the tumbling boys and

their dance?'

Gideon's face suddenly lit up. He pointed his foot

in its clumsy boot and then twirled round, while I

clapped. But the other boys were watching. They

started pointing and jeering.

'See the idiot boy dancing!'

'He is

not

an idiot,' I said, clenching my fists. 'I

will punch any boy who calls him that.'

They laughed harder, because they all towered

over me.

'Who

is

this little red-haired runty lad?'

'Is he new? I've never seen him before.'

They were gathering round us, which made me

nervous.

'He's a rum little fellow! Where's his waistcoat

and cap? He's only half dressed!'

'What's your name, boy?'

'I'll tell you his name – it's Hetty Feather!'

someone said.

I spun round – and there was Saul, grown thinner

and taller, his face pinched. His bad leg bent sideways

and he clutched a cane for support.

The other boys roared at my name. 'The cripple's

talking such rot! Hetty Feather! That's a girl's name.'

'She

is

a girl. She is my foster sister,' said Saul.

He looked at me, his cheeks flushed. 'Remember,

remember, remember, Hetty Feather. You tell Gideon

to remember – but you forgot

me

!'

'He's a

girl

?' said the biggest boy. He seized

hold of me and thrust his hand down my breeches,

though I struggled and shrieked. 'He

is

a girl!' he

yelled triumphantly.

'There's a girl over here!'

'A girl, a girl, a girl in breeches!'

'Come and see the girl, the red-haired girl!'

They were all running towards me. I saw a nurse

in the distance raise her head and stare over at the

hubbub.

'I have to go, Gid, or I shall be in terrible trouble.

But you remember, promise? Remember everyone

at home. Remember

me,

your Hetty.'

I gave him a quick kiss on his cheek. I might have

tried to kiss Saul too, but he spat at me. So I spat

back, then dodged round him and ran.

The boys shouted after me, some of them running

in pursuit. I heard a wail. I turned. Gideon was

waving wildly at me. His mouth was open.

'My Hetty!' he called, his voice cracking.

There was uproar as they all heard him speak,

but I could not stay to congratulate or comfort

him. I shot inside the entrance and ran like a rat,

desperate for cover. I heard bells clanging and knew

it was the end of playtime. I made it undetected all

the way back to the girls' dormitory. I tore off the

jacket and breeches, tugged on my dress and apron

and tippet and thrust my cap upon my head. I was a

girl again. I had got away with it!

Each day was so alike: up in the morning as the

bell rang; dressing, washing, eating, even going

to the lavatory at the allotted hour. We learned the

same lessons every day, reading and writing and

singing and scripture, then the wretched darning

every afternoon. We ate the same meals – porridge

for breakfast, boiled beef or mutton for dinner,

bread and cheese for supper every Monday, Tuesday,

Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday, all

identical – so

Sundays

came as a total surprise.

We were handed special snowy-white Sunday

tippets and aprons, and given a severe warning by

Matron Pigface Peters to keep them spotless. Woe

betide any girl who dribbled her porridge down her

front at breakfast! Then we all trooped off to chapel,

marching in a crocodile. I still did not have a friend

in my own class so I had to trudge along beside

Matron Pigface herself, while Sheila and Monica

walked directly behind and kept kicking the backs

of my legs and treading on my boot-heels.

I turned to try to kick them back, but Matron

Pigface tugged my arm and glared at me.

'Behave yourself, Hetty Feather! Pray to the Lord

above to make you a good meek little maid, not the

total varmint that you are.'

I wasn't sure what a varmint was, but I decided I

wanted to stay one if I possibly could. I didn't want to

be good or meek. I certainly didn't want to stay little so

that all the others could squash me flat. I didn't much

care to be a maid either. If I had to be a foundling, then

the boys seemed to have far more fun.

The Sunday service in the chapel wasn't fun

for any of us, girls or boys. We had to sit as still as

statues on the hard pews. If we so much as swung

our legs, Matron frowned and tapped us. If any

small foundling fidgeted or fell asleep during the

long, long sermon, a big girl would poke her hard

in the back – and doubtless the little boys over on

the other side of the chapel were being subjected to

similar nips and knocks.

The foundlings who formed the choir were the only

children who could mingle, girls and boys together. I

was surprised to see my own sister, Martha, up there

at the front, the smallest child in the whole choir,

looking especially earnest with her spectacles on the

end of her snub nose. She had a very short solo and

sang like an angel, hands folded, head high, mouth

wide open. I felt true sisterly pride, goose pimples on

my arms at the sweetness of her voice. If only Mother

could have been present to hear her!

I blotted out my pew of foundling girls sitting hip

to hip in their ugly brown frocks. I pictured my entire

family, Jem beside me, whispering loyally that he

was sure I could sing every bit as sweetly as Martha,

Nat surreptitiously whittling a piece of wood, Rosie

and Eliza in their Sunday print frocks with their

hair specially curled, Father large and lumbering,

holding his neck awkwardly because the collar of

his starched Sunday shirt was rubbing, and Mother

rocking the sleeping baby, her eyes shining to see

us all together. Gideon would be with us of course,

sitting bolt upright, dancing his toes in time to the

music. I suppose Saul would have to be here too – but

right at the other end of the pew, away from me.

I peered round to see if I could possibly spot the

real Gideon and Saul in the distant sea of brown boys

– and got poked hard in the back for my trouble. I had

to sit still, and pray and sing and listen while the vicar

preached endlessly about miserable sinners. I was

very

miserable and I knew I was a sinner, so I decided I had

better pray hard inside my head so that I wouldn't

tumble straight down to the fiery flames of Hell.

'Dear Lord, please make me a better girl,' I prayed

earnestly, over and over – but as the sermon droned

on and on, I switched the prayer to 'Please God, let

this service finish

soon.'

When it was finally over, I had pins and needles

from the tips of my toes right up to my bottom and I

stumbled when I stood up. We filed out of the chapel,

row after row, while the rest of the congregation

gawped at us. I wondered who all these strange

ladies and gentlemen were. They certainly weren't

hospital staff. I had a sudden wild fancy that they

were parents come to seek out their lost children.

Perhaps my real mother was there, looking for her

lost babe. Perhaps she really

was

Madame Adeline.

I peered at all the ladies, trying to spot a flame

of red hair under all the Sunday bonnets, a flare

of pink lace at the throat of a stark Sunday dress.

'Stop staring, Hetty Feather!' Matron Pigface

snapped.

'But they're staring at me!' I muttered, but not

quite loudly enough for her to hear.

Harriet was one of the big girls supervising our

privy visit when we got back.

'Who

are

all the ladies and gentlemen?' I asked her.

'They are the Sunday visitors,' said Harriet.

'Why are they here?'

'They like to look at us,' said Harriet. 'They will

watch us at our Sunday dinner too. So mind your

manners, little Hetty!'

I was not sure whether she was serious or not,

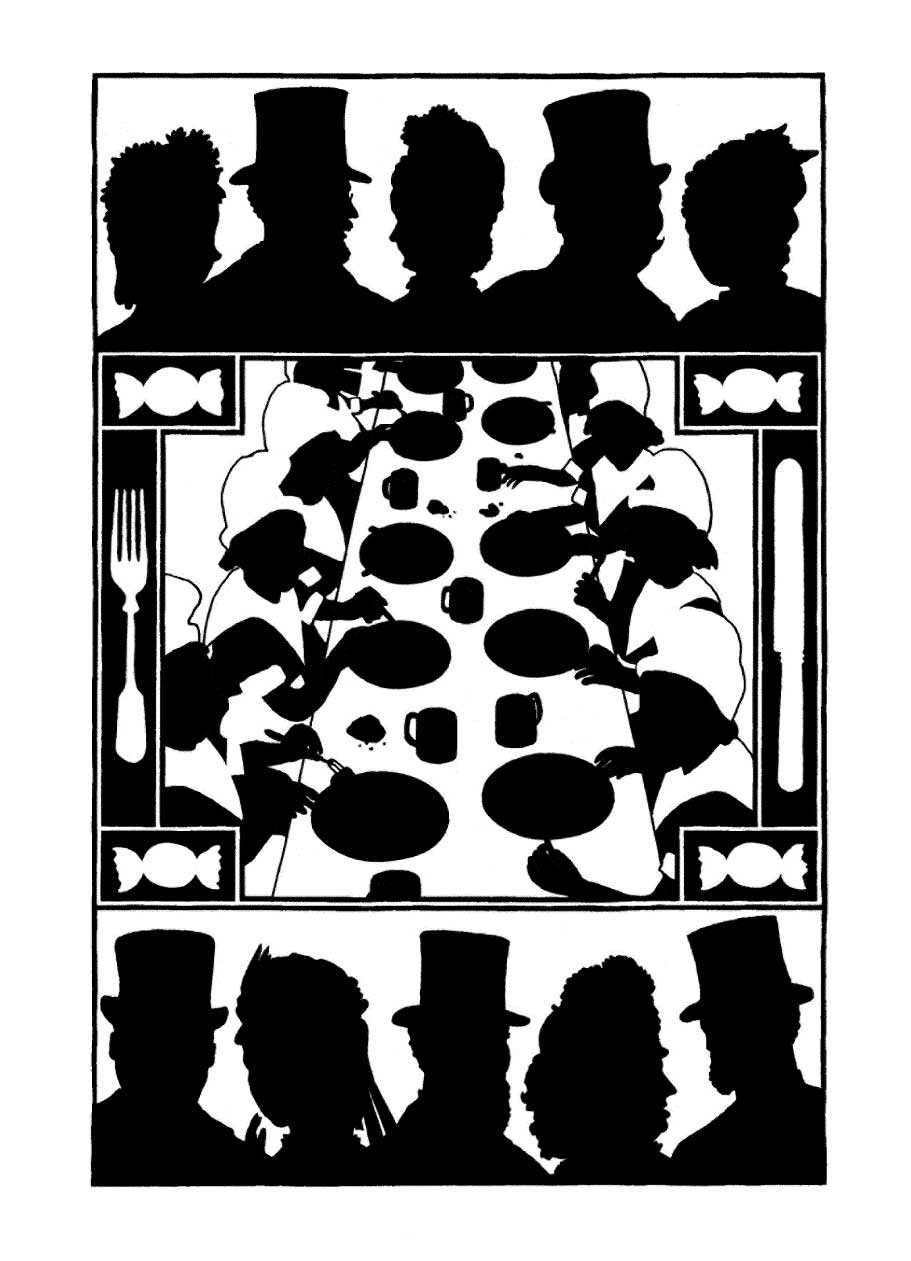

but when we marched into the dining room, one

two, one two, there they were, the ladies and

gentlemen all lined up expectantly. We stood behind

our benches while a big girl said grace in a very loud

sing-song, making her voice extra holy because it

was Sunday, and everyone was staring at her. Then

we clambered onto our benches and the kitchen

maids started serving.

It was roast beef, one slice each, with roast potatoes

and carrots and cabbage from the garden. My special

kind maid pushed her way quickly down to my table

and gave me the biggest slice of beef and the largest,

crispiest potato. She winked at me as she did so.

The ladies and gentlemen surrounding us were

making such a noise I dared to speak myself.

'Thank you!' I whispered, smiling at her. 'You're

very kind to me. What is your name?'

'I'm Ida Battersea.'

'Do I call you Matron or Miss?'

'You can call me Ida. What is your name, dear?'

'I'm Hetty Feather.' I wrinkled my nose. 'It's a

silly name.'

'I think it is a very distinctive name,' she said.

'Oh, I do

like

you, Ida!' I said. I forgot to whisper,

and a nurse came bustling up, glaring at me.

'Were you

talking,

child?' she demanded.

'Oh no, ma'am, it was me. I'm very sorry, ma'am,'

said Ida.

'You must learn to hold your tongue,' said the

nurse, as if Ida was one of us girls.

She flushed and bowed her head, but when the

nurse moved away, Ida pulled a comical face at her

back. I laughed and choked on my hot potato.

Ida had to serve the next table, and as soon as

she was gone, three fine ladies stepped right up to

our table and watched us eat.

'My, they're so neat and dainty! See how they

spoon their gravy so carefully!' said one.

Of course we were neat and dainty. We knew that

if we spilled anything down our Sunday tippets we'd

get our knuckles rapped.

'Aren't the little ones sweet! Do you see that

one with the high forehead? That's a clear sign of

intelligence,' said another, singling out Sheila, who

smirked at her in sickening fashion.

'I'm rather taken with the very little one. She's

not much more than a baby,' said the third. 'Poor

little scrap, I doubt she'll survive the winter.'

I scowled at her, which was a mistake.

'Oh dear, look at that expression! She's a surly

little thing. No, no,

my

one's smiling prettily,' said

the second lady, fumbling in her purse. 'Here, my

dear, a little treat for you.'

She put a wrapped sweet beside Sheila's plate.

Sheila popped the sweet down the front of her tippet

before anyone else could see. Aha! So

that

was why

she'd smiled so.

I knew how to play this game now. The three

ladies trotted further down the dining hall, and

their place was taken by a gentleman and a lady,

arm in arm.

'Oh, I do like the little ones,' said the lady.

I sat up, opened my eyes wide, and smiled.

'That's a dear little love, the one at the end. Look,

she's smiling!'

'Bless the child, she's taken a shine to us!'

I grinned and gurned deliberately while they

oohed and cooed – but they sauntered off without

giving me anything. Sheila saw my face and laughed

at me. She patted the tiny bulge in her tippet where

her sweet was and licked her lips.

But then another lady and gentleman came

nearer, both so fat that his waistcoat buttons were

a-popping and her corsets were strained to bursting

point. They were exclaiming over the meagreness of

our portions, though this Sunday fare was practically

a feast to us.

'I'm sure the children are half starving!'

I sucked in my cheeks and looked mournful.

'See the little one at the end! What a shame, she

needs feeding up. Here, my dear, this is for you.'

The gentleman pressed a slab of toffee in my hand.

I gave him the greatest grin of my life and tucked it

into my tippet immediately, with a triumphant little

nod at Sheila.

Dear Ida came back with a second course for us, a

milk pudding with a splash of red jam. Ida served out

the pudding

and

the preserve, so I got a whole spoonful

of raspberry jam. My spirits lifted considerably. I hoped

Gideon was faring equally well in the boys' dining

room. Ladies often made a pet of him so I thought he

might get singled out and given sweetmeats.

I collected four more boiled sweets myself, so

that I was growing quite a chest under my tippet. I

planned to eat my feast in bed, but as soon as we got

outside after our Sunday meal, the big girls pounced

on us little ones.

'Come on, give us your sweets, fair dos!' they

said, feeling up our cuffs and down our tippets,

practically turning us upside down and shaking us

in their search for our sweets.

One girl snatched my precious slab of toffee, another

gathered up my boiled sweets. I cried and tried to fight

them off but there were too many of them.

'Poor little Hetty! Leave her alone, she's my

baby!' Harriet shrieked, rushing to my rescue.

She managed to save one last sweet, a barley

sugar. 'There you are, my pet. Eat it up quickly before

someone grabs it. Shame on you, girls, descending

on the babes like a swarm of locusts!'

She swept me off with her. I cuddled up close and

sucked my barley sugar while she petted me.

I learned to be more wily the next Sunday,

stowing my sweets under my cap. They made

my shorn hair a little sticky but I didn't care. It

had a good scrubbing on bath night. Meanwhile

sucking my sweets helped the long nights seem less

lonely.

I dreamed of home when I eventually fell asleep.

It was so sad to wake and find myself imprisoned in

the bleak hospital dormitory. I wondered how they

were managing at home without me – especially

Jem. I knew he would be fretting, frantic to know

if I was all right. It gave me an added incentive in

my writing class with Miss Newman. As soon as we

could master our pens sufficiently, we were allowed

to write home.

It was a long letter and it made my hand ache

terribly. Miss Newman wrote it on a board and we

copied it out laboriously:

Dear Mother

I now have the greatest pleasure in writing these

few lines to you, hoping to find you quite well and

happy, as it leaves me at present. Please give my

love to all the family.

I remain

Your affectionate girl

Hetty

We were told to copy it exactly, neither adding nor

deleting anything. Older girls who were fluent

enough occasionally tried to add a few more personal

lines, but Miss Newman had to approve them before

they could be sent.

I was exhausted by the time I reached 'affectionate'

and didn't concentrate hard enough. If I didn't

insert enough

f

s and

t

s

,

or got my

i

and

o

the wrong

way round, Miss Newman put a line through it and

I had to start all over again. I longed to add my own

personal message:

I detest it here and I miss you so and Sheila is mean

and I hate Matron Peters and she stole my rag baby

and I don't wear drawers nowadays.

However, I'd seen other girls have their letters

confiscated if they so much as commented on the

monotonous food or complained about being stared

at on Sundays. I simply inserted two words after

Please give my love to all the family – especially Jem.

After I'd signed my name, I filled the rest of the

page with kisses.

Now that I could write, more or less, I tried hard to

copy some of my picturings down on paper so that my

stories were preserved. It was very hard to

find

any

paper. I dared to steal a sheet from Miss Newman's

special supply in the stationery cupboard, but it

was mostly kept under lock and key. Harriet once

obligingly tore a couple of pages from her exercise

book, but my steadiest supplier was dear Ida. She

slipped me paper bags and greaseproof paper from

the kitchen. I stuffed them down my tippet and went

around crackling all day until I could hide them in

my mattress.

It was hard to find a place to write privately.

Sometimes I sat up in the middle of the night and

scribbled in the dark with a stolen stick of charcoal,

though in the morning I saw my lines of writing

wobbled up and down and sometimes crossed right

over each other.

It wasn't enough to write

my

stories. I wanted to

read new stories too. I had the Bible, and some of the

stories were exciting, but the words were very hard

to decipher. Miss Winterson lent me her book of fairy

tales, and I read them over and over again. I went

to the ball with Cinderella in my glass slippers, I let

down my long hair like Rapunzel, I swam in and out

of underwater coral palaces with the little mermaid.