Hetty Feather (18 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

It wasn't cake. It wasn't anything to eat at all. It

was a tiny book, bound in red, with gilt lettering:

The

Story of Thumbelina.

I opened it up with trembling

fingers. The story was about a very, very small

girl called Thumbelina, and there were

coloured

illustrations

! I saw Thumbelina with pink cheeks

and very yellow hair, tucked up neatly in a brown

walnut-shell bed. I stroked her hair and patted her

tiny quilt and then read the first few pages, though I

had to squint in the candlelight and it was fearfully

cold in the dank washroom.

Dear Ida! She had chosen the smallest book she

could find so I could hide it easily about my person.

Thumbelina was even smaller than me, yet she was

the heroine of her fairy tale, and when I peeked at

the ending I saw she lived happily ever after.

I was frozen solid when I eventually stole back

to bed, but glowing inside, warmed by Ida's loving

generosity. At breakfast I waited until she came to

serve us our porridge and then I grabbed hold of her

hand tightly.

'Thank you, Ida!' I said passionately. 'I do love

you so.'

The other girls giggled, thinking I was simply

thanking Ida for my porridge. But Ida understood.

She gave my bowlful an extra sprinkling of brown

sugar and patted my shoulder, smiling all the

while.

I marched off to chapel feeling very happy. For

once I sat through the long, long service without

fidgeting, because I had the wondrous Nativity

tableau vivant

to gaze at. The participating children

kept still as statues. Even the newborn babe in the

cardboard manger slept peacefully throughout.

Mary was one of the big girls in Harriet's class, thin

and dark and a little gawky, but strangely graceful

now. She knelt before the baby, hands clasped in awe,

her beautiful bright-blue dress draped decorously

about her.

Joseph was one of the big lads, tall as a man,

splendid in his orange striped robe. The shepherds

were arranged artistically on the left, some standing,

some kneeling. There was even a stuffed sheep,

and the smallest shepherd clutched a toy lamb.

The three wise men paraded on the right, wearing

large gold crowns studded with glass jewels. Each

boy sported a long false beard to show they were

very old and very wise. Oh, how I longed to have a

beard too!

Best of all, there were the angels, an entire flock

of them, standing aloft upon the stable roof, in gauzy

white with great feathery wings, Monica amongst

them, pink and pious, her eyes raised upwards.

There was one angel who seemed to be truly

flying, dangling on a rope from the chapel rafters,

his bare feet on the points of a silver star; the

most wondrous angel, with a halo illuminating his

dark curls. You will never guess who it was! My

own little brother, suspended in mid-air, his arms

gesturing gracefully, his toes pointed, dancing down

from Heaven.

'It's Gideon!' I whispered proudly to Polly. 'My

brother Gideon.'

I felt I could sit there in the chapel for ever. I

was so happy for Gideon, and so relieved that he

was well and making such a grand job of this angel

acting. I glowed with pride when I heard the ladies

and gentlemen talking as we ate our Christmas

dinner afterwards.

'Bless the children, they looked so splendid in

the

tableau vivant

.'

'They kept so still, even the tiny ones.'

'The little boy angel was by far the best.'

'Oh, I agree! A true little angel up there

in mid-air!'

I nudged Polly, and happily munched my way

through my roast goose and my plum pudding. We

each had an orange too. Some of us little ones were

inexperienced orange eaters and tried to bite into

the bright dimpled skin. I might have done the same

because we never had oranges at the cottage, but I

watched Polly and copied her as she peeled the skin

away and divided her orange into segments.

We had no official presents as such, but when

we lifted our mugs to take a drink, we discovered

a brand-new polished penny. I hid mine later on top

of Jem's silver sixpence. I went to sleep that night

with Polly's pen under my pillow, Harriet's doll

tucked in beside me, and my tiny book clutched to

my chest.

We were given an orange and a new penny the

next Christmas – and the next and the next

and the next. That was the worst thing of all about

the hospital: the sheer sameness of every single day.

If things

did

change, it always seemed to be

for the worse. Harriet left the hospital to go into

service as a nursery maid. She cried when she said

goodbye, telling me she'd never care for any of her

new nursery charges the way she cared for me. I

missed her dreadfully. She had been so kind to me,

and I'd loved sitting on her lap and being babied.

Thank goodness I still had Polly!

We moved into the upper school, into a different

dormitory. Of course I remembered to transfer Jem's

sixpence to my new bedpost. I had to say farewell

to dear Nurse Winnie and Miss Newman. Thank

goodness Ida could still serve me every day in the

dining room, giving me illicit gifts of raisins and jam

and knobs of butter when no one was watching.

'How are you doing, Hetty?' she'd always ask.

'I'm doing very well, Ida,' I mostly said.

I wasn't doing well, I was doing very badly. I

didn't care for my new teacher, Miss Morley, and she

certainly didn't care for me – or Polly either. Miss

Newman had been strict but she liked both of us.

When we answered correctly or asked an interesting

question, her eyes lit up behind her spectacles and

she seemed delighted to teach us.

Miss Morley stopped asking us to answer

questions, because she knew we'd get them right,

and this seemed to irritate her.

'Don't sit there with that smug expression on

your face, Hetty Feather. We all know

you

know the

answer,' she'd say, and she'd give a false yawn and

encourage all the others to laugh at me.

I couldn't

help

knowing the answers because our

lessons didn't progress. We could mostly all read

and write by now, and do the simplest sums – and

there we stuck, not working our way forward at all,

going over the same dull facts again and again.

There were maps all round our classroom wall

and I'd stare at all the different countries and picture

a flea-sized Hetty sailing across the blue sea and

landing on each pink and yellow and green land.

'Stop daydreaming, Hetty Feather, and attend to

your dictation,' Miss Morley snapped.

'Can't you tell us a little about the countries on

the map, Miss Morley? I wonder what it is like in

great big Africa or India or Japan? Do the children

do dictation there? Do they wear long dresses and

caps, or do they wear short clothes – or maybe if it's

very very hot, no clothes at all?'

The others sniggered and Miss Morley flushed,

though I hadn't meant to be impertinent.

'Stop these ridiculous questions, Hetty Feather.

You don't need to know the answers. It's not as if

you're

ever going to voyage to foreign parts. You're

going to be a servant like all the other girls. You

only need to write a decent hand, read a recipe and

add up your groceries correctly.'

I felt I needed to do so much more! I still hated

the idea of being a servant. I feared I would be a very

bad one. We were taught how to wash clothes and

scrub floors now, helping out with all the household

chores in the hospital. I hated getting hot and

wet. I was so bored I distracted myself by telling

stories in my head, not concentrating on the tedious

housework.

'Use some more elbow-grease, Hetty Feather!'

they'd scream at me. 'Watch what you're doing!'

they'd yell when I started and knocked over my pail

of water.

Polly was as bored as I was, particularly in

lessons. She could not bear our arithmetic sessions

because Miss Morley frequently made mistakes.

Polly pointed out a simple subtraction error on

the blackboard early on, waving her arm earnestly.

'What

is

it, Polly Renfrew? I haven't finished the

sum yet.'

'I know, Miss Morley, and I'm sorry to interrupt,

but I don't think you've noticed that you've

subtracted an eight from a three and put the

answer as five, and yet you haven't borrowed

ten from the next line so that nine is incorrect,' she

said helpfully.

She wasn't being impertinent. At this stage she

didn't realize that Miss Morley's grasp of arithmetic

was extremely shaky. She thought she'd simply made

a silly slip and would be grateful for her intervention.

Grateful! Miss Morley flushed an ugly scarlet

and rubbed the entire sum from the blackboard.

'How

dare

you admonish me, Polly Renfrew! Come

out here.'

Polly stepped forward uncertainly.

'Hold out your hand.'

Polly held it out politely, as if Miss Morley was

going to shake it. But she seized her long ruler

instead and went

whack whack whack

across Polly's

soft white hands.

We all jumped. Our eyes stung. We'd been

threatened with whippings and beatings many

times in the infant school, but the only actual

physical punishment any of us had received was an

impatient tug on the ear or a light tap on the backs

of our legs. This was a cruel assault. We could see

the painful red weals on Polly's palms. Polly's face

crumpled and she started crying.

I was beside myself. 'How dare you hit her when

she's done nothing wrong at all, you cruel, wicked

woman!' I cried, and I seized her ruler and hurled

it into a corner of the classroom. The whole class

gasped. I was a little shocked myself. I hadn't quite

meant to say those words, they just spurted out of

my mouth in a torrent.

'Come here, Hetty Feather!' Miss Morley said. 'I

will not stand for this behaviour!'

I thought she would retrieve her ruler and beat

me to within an inch of my life. I decided I would

not cry like poor Polly. I would hold my head up high

and be a brave, unflinching martyr. She could beat

me three times, six times, even a dozen; she could

beat my hands into a bloody pulp but I would not

murmur or shed a tear. I would stare back at her

like a basilisk, wishing her dead.

But she didn't beat me even once. She seized hold

of me by the wrist, digging her nails in hard, and

tugged me right out of the classroom. I thought she

was simply standing me in the corridor and decided

I didn't mind in the least. I could just stand and

picture the past in my own private daydream. But

Miss Morley marched me right along the corridor. I

realized she was taking me to Matron.

My heart started thudding then. The senior

school matron made Pigface Peters seem sweet as

sugar. Matron Bottomly was thin and pinched, with

a permanent pucker in her forehead. She had a big

hooked nose like a beak and always looked as if

she'd like to peck you very hard. Matron Bottomly

had already told me off several times for talking

in corridors, she had chastised me for tearing my

dress when I fell over playing tag, she had made me

scrub a whole floor twice over because I'd left one or

two slimy soap smears. (Oh, how I wished Matron

Bottomly had slipped on them and landed on her

bony stinking bottom!) What might she do when

she knew I'd shouted at a teacher, taken her ruler

and thrown it away?

I felt I

might

cry now, but I stared hard, scarcely

daring to blink in case the tears started spilling. I was

pushed unceremoniously into Matron Bottomly's

room and forced to stand there in front of her while

Miss Morley gave a highly exaggerated account of

my rebellion.

'It was total insubordination, actual physical

violence!' Miss Morley declared dramatically, drops

of spittle on her chapped lips.

Matron Bottomly rose from her desk and looked

me up and down. I started trembling but I

looked her up and down back, my fists clenched.

I

will not cry,

I said inside my head.

I will not cry,

no matter what they do to me. I can bear it, whatever

it is. They cannot

kill

me. I will be brave.

'You are a child of Satan, Hetty Feather,' said

Matron Bottomly. 'You have his Hell-red hair and

his flaming temper. We must quench this devilish

fire. You must be taught a severe lesson.'

I was so crazed with fear I thought she meant a

literal lesson. I dared to breathe out, because I knew

I was always quick to learn. But this punishment

had nothing to do with books.

'Take hold of her, Miss Morley,' said Matron

Bottomly.

They each seized a wrist and pulled me to the door.

They dragged me down the corridor. I thought they

were taking me to the boys' wing. We'd heard fearful

rumours that the baddest big boys were beaten with

a cat-o'-nine-tails. Perhaps they were now going to

whip me with this dreadful instrument! I gritted my

teeth, though they were chattering now.

But when we reached the grand staircase, they

dragged me up one flight of stairs and then another,

right to the very top of the building, to a little attic

room in the tower.

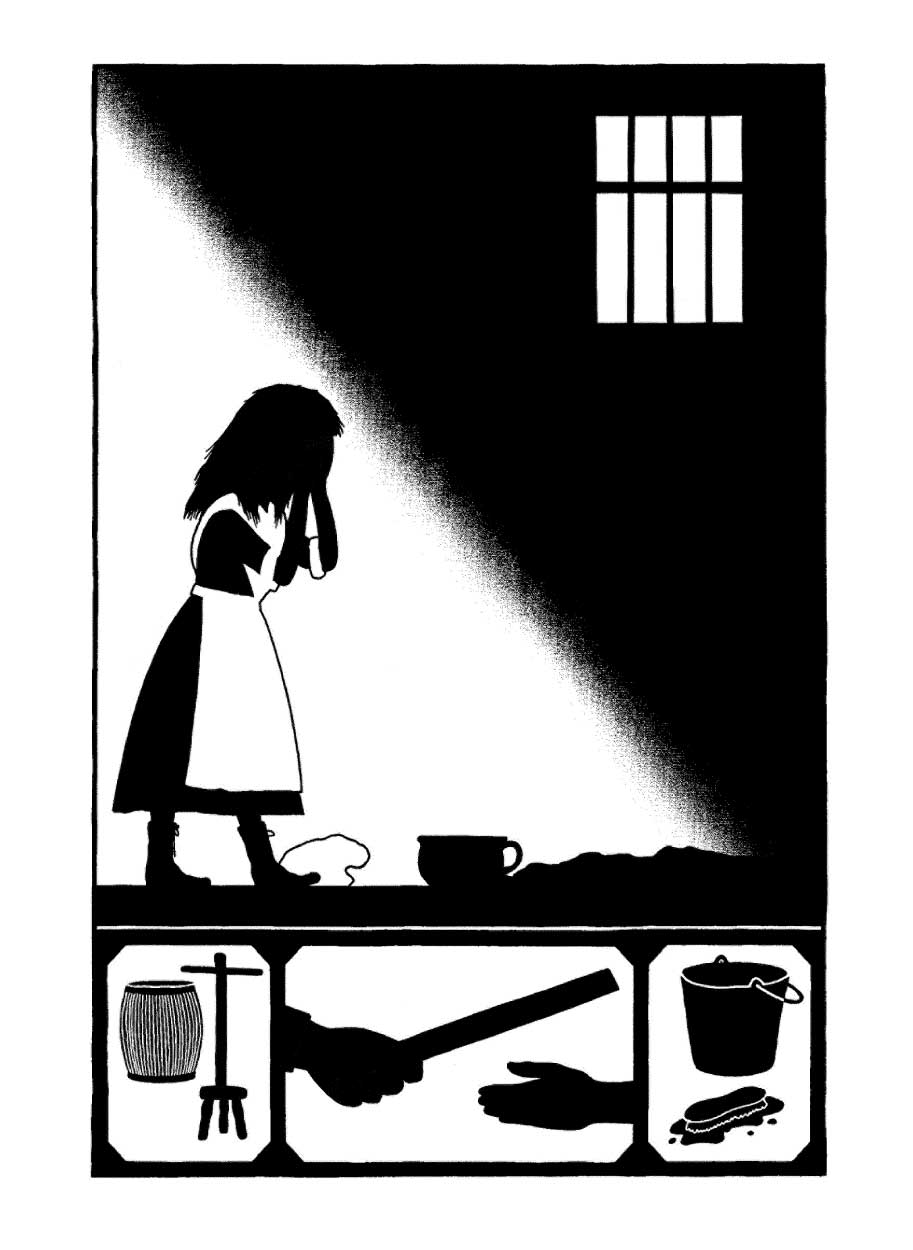

They opened a door at the end. It was empty

apart from an old blanket and a chamber pot.

'No!' I cried. 'No, please – you can't put me

in there!'

'Oh yes we can, Hetty Feather. You stay here and

pray to be a better girl,' said Matron, and she thrust

me inside. The door slammed shut and I heard the

sound of a key turning. I was locked in! I heard their

footsteps retreating. Perhaps they were simply

trying to frighten me. They would come back any

minute. They couldn't leave me locked in here!

There was only one very small window, set high

up in the wall. It had bars across, as if this was truly

a prison. I tried jumping up but could only catch a

glimpse of sky. I was very small, but there was no

way I could ever wriggle through those bars – and it

was a sheer drop anyway.

I tried hurling myself against the door, knocking

all the breath out of my body. It held fast. I was truly

a prisoner.

'Well, what do I care?' I said aloud. 'I will show

them. It is not so very dreadful to be locked in for

an hour or two. They will have to come back soon

because it is nearly dinner time. Meanwhile I shall

amuse myself. I shall pretend I am a princess locked

up by two evil wicked witches in a tall tower.'

I pictured this determinedly, inventing a

magnificent Prince Jem who climbed the tower

and rescued me. We lived happily ever after in his

wondrous kingdom – while the two witches were

locked up in their own tower for ever.

I amused myself with this story for quite a while,

but my stomach started rumbling. I could not hear

the clock chiming from my isolated prison but I was

certain it was long past dinner time now. So they

intended to starve me, did they? Were they going to

keep me locked up right until supper time?

I kept staring at the chamber pot. It was clearly

there to be used, so perhaps I truly was to be left

for hours yet. I decided I would not sit on the

pot, no matter what. It would be too humiliating

for the contents to be inspected by Matron and

Miss Morley.

The hours went by, and I fidgeted on my blanket,

trying to divert myself. In the end I simply had to

squat on the pot in an undignified fashion or have

an accident. I waited further hours, and after a

long, long while all my picturing skills faded. I could

think of nothing to divert myself. Surely it would be

supper time soon?

They

had

to let me out for supper. They couldn't

leave me locked up in this tiny room until I starved

to death. I listened desperately for the sound of

approaching footsteps, but there was just endless

silence. I tried singing to make a sound in the room,

but my voice sounded too high, too weird, as if I was

a crazy girl.

I tried to lie down on the blanket, but the

floorboards were hard and the blanket smelled

stale and musty when I nuzzled into it for comfort.

I remembered my long-ago rag baby, and started

weeping. Once I'd started I couldn't stop. I sobbed

frantically, but still no one came.

'I'm sorry!' I shouted. 'Please come back, Matron!

I've learned my lesson now!'

But she didn't come. It seemed to be getting darker

in the small room. Oh my Lord, was it evening now?

Were they going to keep me locked up all night long?

I shouted until my voice cracked, but still nobody

came. I threw myself about the attic, kicking and

screaming. I tore off my stupid cap and pulled my

own hair. It was long again now, in two tight plaits,

but I undid them and shook my head in despair, my

hair wild about my shoulders.

I was so thirsty from crying I could barely

swallow. How could they leave me without even

a few sips of water? They

had

to come back soon

or I would surely die. Was that what they really

wanted

? Oh dear Lord, what if they never came

back? What if I mouldered up here in my dark prison

for ever? What if they waited until I was a grisly

skeleton in scraps of brown, crumbling to dust?

Then, at long, long last, when it was getting really

dark, I heard footsteps coming along the corridor,

and the sound of a key in the lock.

'Oh, at last!' I said. 'I'm so sorry. You will let me

out now, won't you?'

It was Nurse Macclesfield, one of the senior

school staff. She was carrying a bucket and a plate

and a mug. 'Of course you are sorry, Hetty Feather

– and you'll be sorrier still by morning!'

'What! You're not going to keep me locked up

here all night!' I said in horror.

'You must learn the error of your ways, you

wicked girl.' She seized my pot, pulling a face of

disgust, and emptied it into her bucket. Then she

put the plate and mug down on the floor and went

to close the door on me again.

'No! Oh, Nurse Macclesfield, have pity on me!

Let me out!'

I tried to cling to her, but she pushed me away.

'Don't you dare try to attack me the way you

attacked poor Miss Morley. She said you were like a

wild beast. It's time you were tamed!'