Hetty Feather (5 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

When they were all gone, he shook his

head at us. 'Such long faces! Are you missing

young Saul?'

'Most dreadfully, Father,' I said.

He blinked at me. 'Why, Hetty, you do surprise

me,' he said. 'You two were always fighting! No

doubt you're full of remorse now?'

I nodded. I wasn't yet sure what remorse meant,

but the cold, sour, sick feeling in my stomach seemed

to sum it up.

'Poor child,' said Father, patting me.

I climbed up onto his great lap and nuzzled my

face against his chest. I could hear his heart going

thump against my cheek.

'Mother won't take me away, will she,

Father?' I said into the rough cotton of his smock.

'Nor Gideon?'

I waited. I felt Father take several deep

breaths.

'Not till next year, my sweetheart, when you are

both much bigger.'

'No! No, not then, not ever!' I shrieked,

pummelling him with my fists.

'Stop that now, missy!' said Father, catching

both my flailing hands in his large one. 'You've

shrieked enough today, I'm told. There's no

point wailing when it can't be helped. Now hush

and listen. Mother and I love you, love Gideon,

love little Eliza just like our own children. We still

love Saul—'

'And Martha,' I said.

'And Martha,' said Father, seeming surprised

I'd remembered her. 'But you're not our children,

you're little waifs from the Foundling Hospital. You

came to us as tiny babies. Mother has a knack with

specially frail babies. She rears you up until you're

fat and rosy-cheeked.' He gently poked me in the

cheeks with his thumb and finger, but I wriggled

free, a new thought having struck me.

I was remembering the pig out in the back yard.

Mother had a piglet every year, pale and puny. She

fed it and fattened it until it could barely sway on its

trotters, and then Father came along, and although

we weren't supposed to watch, we heard

squeal-

squeal-squeal,

and the next day there was fresh

pork on our plates.

'Is she fattening us up to

eat

us?' I said, gazing at

Father as if he was an ogre.

He stared back at me, slack-mouthed, and

then he roared with laughter. 'Oh, Hetty, Hetty,

you're a funny one,' he chortled. 'Of course no

one's going to eat you! Mother will take you back

to the Foundling Hospital when you're big enough,

and you'll live with lots and lots of other girls.

Martha will be there so you'll have one sister. And

you'll be with the boys, Gideon, and Saul will be

your brother.'

'I want to be with Hetty,' said Gideon, but Father

paid him no heed.

'We need to be

with you,

Father. And Mother. And

my Jem,' I said. 'Please can't we stay? I promise I'll

be very, very, very good. I'll never shout or kick or

cry ever again.'

'You're a caution, Hetty,' said Father. 'We would

love you to stay here with us. We'd like to keep

all our dear foster children, but you do not belong

to us. You belong to the hospital. All foundlings

must be returned by their sixth birthday. Don't

look so worried. I'm sure they will be kind to you

as long as you are a sensible girl, Hetty. They will

school you properly and teach you to be a good

Christian child.'

'Will we live there for ever?'

'No, no, they will train you up to be a servant

girl and you will go away into service when you are

fourteen,' said Father.

'Like Bess and Nora?' I said.

'Just like our Bess and Nora,' said Father. 'And

then I dare say you can come home to us once a year

just as they do.'

I pondered. Last Mothering Sunday I had admired

my big sisters in their fancy print dresses and fine

stockings when they'd travelled home on a visit.

But they'd told Mother tales of cross cooks who beat

them over the head with ladles and sly masters who

tried to sneak kisses.

'I do not

want

to be a servant girl,' I said.

'Will I be a servant girl?' asked Gideon.

'Don't be dim-witted, lad!' said Father. 'No, no,

I dare say you will be a sailor or a soldier boy like

our Marcus.'

'I

will be a sailor or a soldier and go adventuring,'

I said.

'You are a very strange pair,' said Father, sighing.

'Now jump down and give me a little peace.'

'But you must tell us about the hospital, Father!'

I demanded.

'Hetty, I don't know anything about the

hospital. I've never even set foot inside it. I just

know it's a good place for little children and you

need never say you're ashamed to come from

there,' said Father. 'Now stop plaguing me, girl. My

head's aching.'

Father might never have been to this Foundling

Hospital – but Mother had.

'Come with me, Gideon,' I whispered as Father

sucked on his pipe and closed his eyes.

I tiptoed up the stairs, tugging Gideon

behind me.

Rosie was guarding the door to Mother's bedroom,

but I was bold.

'Father said we must talk to Mother,' I said.

I heard Gideon gasp at my outright lie. Rosie

hesitated, but I pushed right past her determinedly.

It was dark in Mother's room, the curtains drawn

shut as if it was night-time. I could just make out

the shape of Mother lying on her back. I wondered if

she'd gone to sleep, but when I clambered carefully

up onto the bed, her arm came out and held me

tight. I hauled Gideon up too and he nestled on her

other side.

'My lambs,' she murmured.

'Mother, Father has told us about the hospital. Is

it truly a good place?' I asked.

I felt Mother stiffen. She swallowed hard. 'Of

course it is a good place, Hetty,' she said.

I wondered if Mother could be a liar too. I lay

thinking about it.

'Did Saul cry a lot when you said goodbye?'

I asked.

Mother might be a brave liar, but she wasn't

foolish. 'Yes, he cried,' she said.

'And did Martha cry too?'

'Yes, Martha cried too.'

'I shall cry,' Gideon whispered.

'I shall scream and kick and be so bad they

won't let me stay, and then Mother can take me

home,' I said.

I had loved Martha much more dearly than Saul

but I had mostly forgotten her. However, I could

not get Saul out of my head for months. I thought

of him living in this huge hospital with so many

other boys. I knew most boys weren't gentle and

protective like my dear Jem. The village boys

had often jeered and pointed at Saul, imitating

the lopsided way he walked. One boy had pushed

him hard and then laughed when he toppled over.

I thought of all the foundling boys laughing and

pointing and pushing Saul, and my eyes brimmed

with tears.

Then I thought of all those boys mocking Gideon

in turn. My fists clenched. I resolved to fight anyone

who dared hurt my special brother. I was certain

they would not dare hurt

me.

I was famous for my

temper in the village. I might be the smallest but I

was always the fiercest in any scrap. Mothers came

and told tales to

my

mother about hair-pulling and

kicking and sometimes outright punching. Poor

Mother was mortified. She tried reasoning with me

but I reasoned back.

'They called me names, Mother. Half-pint

and Ginger and Runt. I said my name was

Hetty and they just laughed. So I hit them and

they stopped.'

'Jesus said to turn the other cheek,' said

Mother.

Maybe Jesus wasn't teased the way I was. I

thought hard, trying to remember the Bible stories

I heard at Sunday school.

'God

said, an eye for an eye and a tooth for a

tooth,' I declared, imitating the solemn holy tone of

the Sunday school teacher. I hoped it would make

Mother laugh. I knew I was in danger of yet another

paddling.

This suddenly started up a new fear.

'Do they punish the children at the hospital,

Mother?'

'Not if they're good girls and boys,' Mother said.

This was not reassuring. I thought hard.

'Is that why they're there? Because they're

bad?'

'No, no, no. It's because their own mothers can't

look after them,' said Mother.

'Why can't they?' I asked.

Mother sighed. 'There never was such a girl for

questions. You make my head ache, Hetty.'

'Please tell, Mother!'

'Well, dear, some ladies have babies and they

can't look after them,' said Mother.

'Why can't they?' I persisted.

'Perhaps they're very poorly. Or they haven't

got a dear husband like Father to give them a

proper home. The ladies don't want to go into

the workhouse' – Mother whispered the word

and shuddered – 'so they take their babes to the

Foundling Hospital.'

'Do they cry when they say goodbye?'

'I'm sure they cry a good deal,' said Mother.

'Did my first mother cry?'

'I'm sure it fair broke her heart to part with you,

Hetty,' said Mother.

'Why can't I go and live with that mother now,

Mother, instead of being sent back to this hospital?

I don't need looking after.

I

can earn money. I

could sing and dance so that people throw pennies

at me.'

'You can't carry a tune to save your life, Hetty,

so maybe they'd throw tomatoes,' said Mother. 'No

dear, you don't belong to your mother now. You

belong to the Foundling Hospital.'

I did not want to belong to an institution. I

wanted a mother. I crept off by myself, squeezing

into the tiny space at the back of the pigsty and

the privy. It was private because everyone else

was too small to squeeze through the gooseberry

bushes and brambles to sit there. I wasn't

comfortable because there were nettles and it

smelled bad, but I didn't care. I pulled my skirts

down over my bare legs, put my head on my knees

and wept.

After a long time I heard them shouting for me. I

stayed where I was. Then there were footsteps.

'Hetty? Hetty!' Jem called.

I did not reply to him, but I was sniffing hard.

'Oh, Hetty, I know you're in there,' said Jem.

'Come out. Please!'

I did not budge.

'I'm too big to come in and get you,' said Jem.

I heard the bushes rustling, then Jem swearing.

'That's a bad word!' I said.

'I know it's a bad word. Anyone would say it

if they were scratched all over by brambles,' Jem

panted.

'Do

come out, Hetty.'

I simply wouldn't.

'Then I will have to try to get in,' said Jem,

sighing.

He forced his way forward, thrusting his arm

through the bushes until his hand j-u-s-t reached

my bare foot. He held it tight. I curled my grubby

toes into his palm.

'There now,' Jem whispered.

'Oh, Jem,' I said, sobbing.

'I can't bear you fretting about the hospital,' he

said.

'I'm not going,' I said.

There was a silence as we held hand and foot.

'I think you have to go, Hetty,' said Jem. 'But

perhaps I could go too. We'll pretend

I

am a foundling

boy. Yes, I can take Gideon's place and he can stay

with Mother.'

'Dear Jem! I wish you could. But Mother and

Father wouldn't let you,' I said.

There was another silence.

'I will be so sad,' I said. 'I will have to stay there

soooo long.'

Jem had taught me how to count to ten. I tried to

count on my fingers.

'I will be there one two three . . . lots and lots of

years,' I said dolefully.

'I think it is nine years, Hetty. And then you will

be fourteen and quite grown up. And do you know

what will happen then?'

'I will have to be a servant, and cooks will hit me

and masters will kiss me,' I said.

'Maybe for a short while. But then I will come

to fetch you and look after you, and as soon as you

are old enough I will make you my wife. I know I

am your brother, but not by blood so we can marry!

We will have our own cottage and work on the farm

and you will keep house and look after our babies.

It will be just like our games in the squirrel house,

but

real,

Hetty,' said Jem.

'Really

real?'

'I promise,' said Jem.

I didn't always keep my promises, but Jem

did. I seized his hand, kissed it passionately, and

then crawled out of my hiding place to give him a

proper hug.

Thoughts of the Foundling Hospital still

loomed, but at least I had a wondrous future

ahead of me. I just had to wait one two three

four five six seven eight nine years, endure a

couple more while I dodged blows and kisses as

a servant, and

then

I would be sweet sixteen and

Jem's bride.

I dressed up in Mother's best white Sunday

petticoat, clutching a posy of buttercups and daisies,

and tripped around on Jem's arm, picturing for all

I was worth.

'You are my lovely big handsome husband, dear

Jem,' I said.

'You are my very fine little wife, dear Hetty,'

said Jem.

The others laughed at us, especially Nat,

but we didn't care. Gideon didn't laugh but he

looked wistful.

'I want to be your husband, Hetty,' he said.

'No, Gideon, Jem has to be my husband, but

you may come and live with us and be our big boy,'

I said kindly.

I was out one day in the meadow playing Bride

with my husband and big boy when I heard distant

cheering and hurrahs, as if half the village were

coming to applaud our marriage. I looked over the

grass, squinting in the sunlight. I could see no one.

They must be processing along the other side of the

tall hedgerow.

Then I saw a gigantic grey head poking up above

the hedge – a

huge

head with wrinkled skin and a

tiny eye and the longest nose in all the world. I knew

what it was!

'Oh my stars! E is for

Elephant

!' I gasped. 'There

is an elephant walking along the lane.'

Jem was facing the wrong way. He did not

take me seriously. 'Has it come to our wedding

as a guest?'

'Don't picture T is for Tiger,' said Gideon. 'I don't

like his teeth.'

'I'm not picturing! The elephant is

real,'

I said,

tugging at them. 'Look!'

They turned and saw the head bobbing along

above the hedgerow for themselves. Jem shouted,

Gideon shrieked.

'Come on, let's see it properly,' I said, grabbing

their hands.

'No, no, it will eat us!' Gideon cried.

'Don't be such a

baby.

Come

on,'

I commanded.

Jem and I hauled him along between us. We ran

diagonally across the meadow towards the stile. The

clapping and cheering grew louder, the vast head

more wondrous the nearer we got.

When we reached the stile, Jem lifted me up,

and then Gideon, and then we all jumped out

into the lane. There was the elephant plodding

along the path, a real true elephant with such

wrinkled skin, such huge legs, such an immense

belly! A man in a military coat and great black boots

strode along beside the beast, leading him like a dog

on a chain.

Another man capered about beside them,

the oddest creature I had ever seen, with hair

sticking up on end and a bright red nose, his feet

in great black shoes that flapped comically. He

was banging a drum and dancing. Two big boys

danced along beside him, dressed in the oddest

clothes – sparkly silver shirts and very short

breeches and white

tights.

Jem's mouth hung open

in shocked horror, but Gideon pointed in awe.

These boys paused and suddenly went forward into

a tumble, over and over and up in the air and over

and over again.

'Oh my stars!' said Jem, overcoming his scorn

at their girlish garb. He could go head over

heels and stand on his hands, and frequently did

so to amuse me, but he couldn't possibly caper like

these boys.

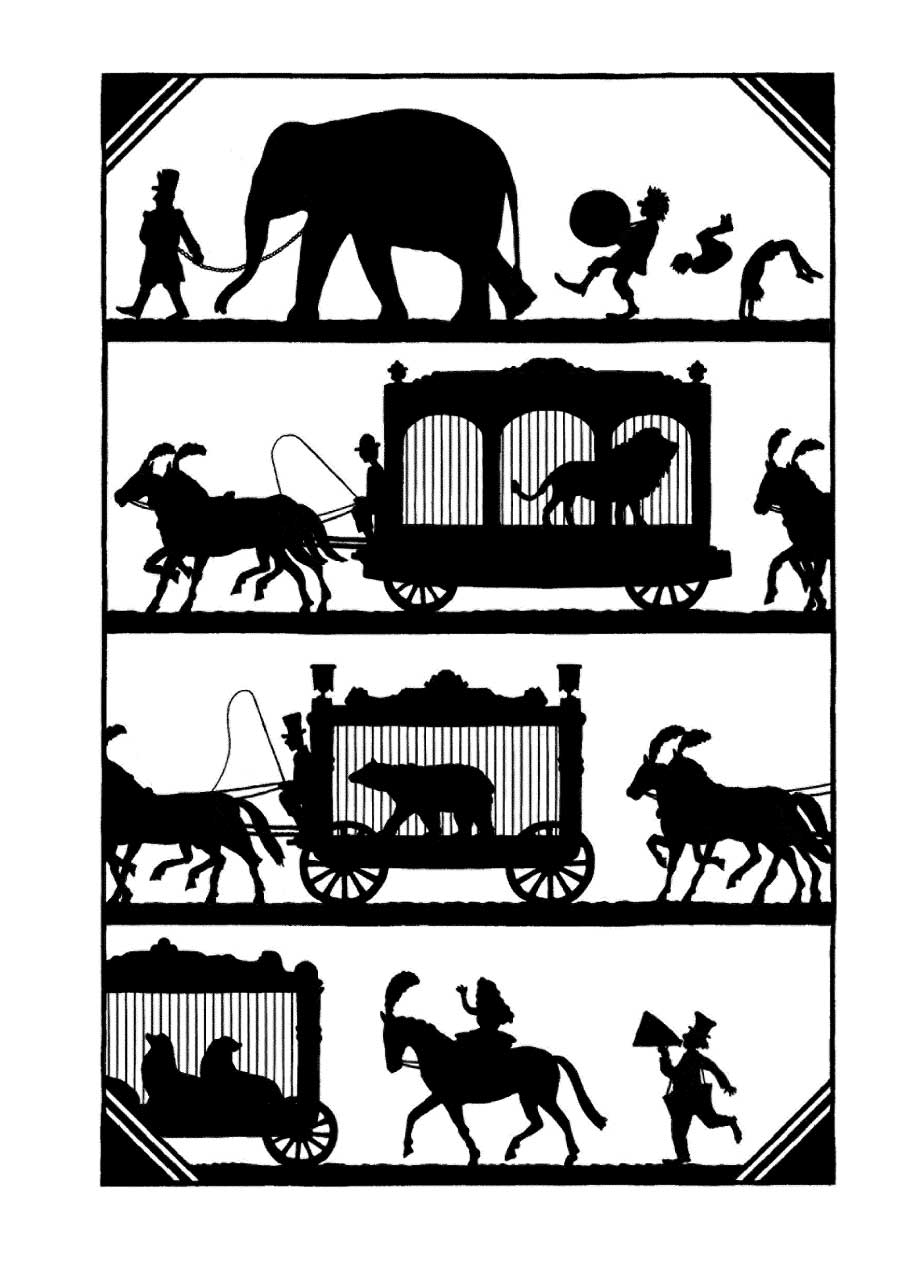

Then came great wagons painted scarlet and

emerald and canary yellow. There was a message

written in curly writing on the sides of each one.

I knew my alphabet but I couldn't figure words

properly yet.

Jem read it for us:

'The Great Tanglefield Travelling Circus.

Observe Elijah, the largest elephant in the entire world.

See the exotic animals in our vast menagerie.

Gasp at Fair Flora dancing on the tightrope for your delight.

Chortle at the antics of Chino the Comic Clown.

Marvel at Madame Adeline and her star troupe of horses.

Hurrah for Tanglefield's Travelling Circus!'

Almost at the end of this magnificent procession

rode a beautiful lady in sparkling pink – wearing

no dress at all, just the merest stiff frill. Her long

flame-red hair tumbled past her bare shoulders.

'Just look at that lady with scarcely any clothes!'

said Jem.

'See her tiny shoes! Oh, I wish

I

had little shoes

like that instead of big ugly boots,' said Gideon.

'Look at her hair!' I said in rapture. 'She has red

hair just like mine! See, see!' I repeated, jumping up

and down.

The wondrous woman raised her hand and waved

to us, and we waved back wildly, honoured to be

noticed.

Another comical man with a red nose and bizarrely

big breeches came capering along at the very end,

speaking into a large horn so that his voice boomed

out above the hubbub.

'Come to Tanglefield's Travelling Circus tonight

at seven, or Saturday at two. The show will be

in Pennyman's Field: adults sixpence, children

threepence – a total bargain, so come and see and

wonder. Come to Tanglefield's Travelling Circus

tonight . . .' He recited it again and again until

the procession was out of sight and his voice a

tinny whisper.

'Oh, Jem, Gideon, we must go to the circus!' I

said, jumping up and down.

'We must, we must, we must!' said Gideon,

jumping too, pink in the face.

'But we haven't got ninepence,' said sensible Jem.

'I have the two pennies that Mrs Blood gave me at

the Otter Inn for collecting up all the tankards, but

that is all.'

'We will ask Mother,' I said.

But Mother shook her head. 'Of course I haven't

any spare pennies for such a senseless thing as a

circus. And even if I had, I wouldn't let you go. Rosie

told me they were near naked in that procession!'

'They were so lovely, Mother, especially the lady

all in pink spangles on a white horse. She had red

hair, just like mine!'

'Yes, pink spangles!' said Mother, shuddering. 'A

grown woman flaunting herself in front of decent

folk, and men capering about foolishly, and a dreaded

beast all set to run amok and trample everyone. It

shouldn't be allowed. Of course I'm not spending

precious money on such a wicked show.'

'Don't spend your money, Mother, spend mine!'

I said.

'What do you mean, Hetty?' said Mother,

frowning. 'You don't have any money, you silly

little girl.'

'I do, I do! The Foundling Hospital gives you

money for me.'

'Don't talk such nonsense, child. That money is

to feed and clothe you, not send you to a heathen

show like a circus.'

'Well, don't give me any food any more, and don't

make me new frocks or buy me boots. I'd much

sooner go to the circus,' I declared.

'I'll certainly send you to bed without any supper,'

said Mother. 'Now hold your tongue, miss.'

I

couldn't

hold my tongue. I wanted to go to

the circus and see Elijah the performing elephant

and all the other animals I'd heard grunting

and growling inside the wagons. Maybe there

were lions or tigers, wild wolves, even a white

unicorn with a silver horn. I wanted to see Flora

dancing on the tightrope, I wanted to see the

comical clown, and oh oh oh, I so wanted to see

Madame Adeline, the flame-haired lady in pink

spangles.

I started to protest bitterly but Jem put his hand

over my mouth. 'Be quiet, Hetty,' he said, tugging

me away from Mother.

'But I don't want to be quiet! I want to go to the

circus!' I persisted.

'Ssh! I might know a way,' said Jem. 'Just keep

your mouth shut and wait till I tell you.'

I clamped my lips together and stomped off after

him. Gideon stayed with Mother, climbing up onto

her lap. He always hated it when I grew stormy. He

was so fearful that I'd get paddled – far more fearful

than me.