Heaven: A Prison Diary (22 page)

Read Heaven: A Prison Diary Online

Authors: Jeffrey Archer

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous

Why would

anyone risk losing so much for a couple of vodkas?

Linda leaves at

midday so I spend four of the next six hours editing

Belmarsh,

volume one of these diaries.

During the

evening I read

Here

is New York

by E. B. White, which Will

gave me for Christmas. One paragraph towards the end of the essay is eerily

prophetic.

The subtlest

change in New York is something people don’t speak much about, but that is in

everyone’s mind. The city, for the first time in its long history, is

destructible. A single flight of planes, no bigger than a wedge of geese, can

quickly end this island fantasy, burn the towers, crumble the bridges, turn the

underground passages into lethal chambers,

cremate

the

millions. The intimation of mortality is part of New York now; in the sound of

jets overhead, in the black headlines of the latest edition.

This was

written in 1949, and the author died in 1985.

11.00 am

Four new

prisoners arrive at the hospital from Nottingham, looking lost and a little

disorientated. I’m surprised that Group 4 has deposited them before lunch as

they don’t usually arrive until around four in the afternoon.

‘It’s New

Year’s Eve,’ explains Linda.

‘They’ll all

want to be home by four.’

Linda checks

her books and tells me that NSC had a turnover of just over a thousand

prisoners during 2001, so after eleven weeks, I’m already something of an old

lag.

Mary and I

usually invite eight

guest

to dinner at the Old

Vicarage on New Year’s Eve.

This year I’ll

have to settle for a KitKat, a glass of Ribena and hope that Doug and Clive are

able to join me.

6.00 am

The camp is

silent, so I begin to go over volume one of these diaries. Reading through

those early days when I was so distressed, I can’t believe how much I have made

myself forget. And this has become even more pronounced since my appointment as

hospital orderly, where I have everything except freedom and the daily company

of my wife, family and friends; a punishment in itself, but not purgatory and

certainly not hell.

Mr New drops

into the hospital to say his farewells. He leaves NSC tonight and will, on 8

January, change his uniform for a suit, when he becomes a governor at Norwich

Prison. He’s taught me a great deal about good and evil during the past three

months.

I miss my wife,

I miss my family and I miss my friends. The biggest enemy I have to contend

with is boredom, and it’s a killer.

For many

prisoners, it’s the time when they first experiment with drugs. To begin with,

drugs are offered by the dealers for nothing, and when they demand more, in

exchange for a phonecard and an ounce of tobacco or cash, and finally, when

they’re hooked, they’ll give anything for a fix – including their life.

Tonight, the

Lincolnshire constabulary informed sister that a former prisoner called Cole,

who left NSC six weeks ago, has been found under a hedge in a quiet country

lane.

He died from an

overdose.

Happy New Year.

6.00 am

I continue to

edit

A Prison Diary Volume One –

Belmarsh: Hell

.

Mr Berlyn drops

in to tell me that he already has plans for my CSV work should my sentence be

reduced, and this even before the date of my appeal is known. He wants me to

work in an old-age pensioners’ home, as it will be out of sight of the press.

He also feels I would benefit from the experience. I had hoped to work in the

Red Cross shop in Boston, but Mr Berlyn has discounted that option after Maria

brought in, without permission, some books for me to sign before Christmas to

raise money for their Afghanistan appeal. The Rev Derek Johnson, the prison

chaplain, has been to see him to plead their case, explaining that he is in the

forgiveness and rehabilitation business. Mr Berlyn’s immediate retort was, ‘I’m

in the punishment and retribution business.’ He must have meant of prisoners; I

can’t believe he wishes to punish a hard-working, decent woman trying to run a

Red Cross shop.

Linda looks

very tired. She’s worked twentyone of the last twenty-four days. She tells me

that she’s going to apply for a job in Boston.

My only selfish

thought is that I hope she doesn’t leave before I do.

Doug turns up

at the hospital for his nightly bath and to watch television. He’s now settled

into his job as a driver, which keeps him out of the prison between the hours

of 8 am and 7 pm. I wonder if, for prisoners like Doug, it wouldn’t be better

to rethink the tagging system, so he could give up his bed for a more worthy

candidate.

7.30 am

Morning surgery

is packed with inmates who want to sign up for acupuncture. You must report to

hospital between 7.30 and 8 am in order to be booked in for an eleven o’clock

appointment. Linda and Gail are both fully qualified, and ‘on the out’

acupuncture could cost up to £40 a session. To an inmate, it’s free of charge,

as are all prescriptions.

The purpose of

acupuncture in prison is twofold: to release stress, and to wean you off

smoking. Linda and Gail have had several worthwhile results in the past. One

inmate has dropped from sixty cigarettes a day to three after only a month on

the course. Other prisoners, who are suffering from stress, rely on it, and any

prisoner who turns up for a second session can be described as serious.

However, back to the present.

Eight inmates suspiciously

arrive in a group, and sign up for the eleven o’clock session. They all by

coincidence reside in the south block and work on the farm, which means that

they’ll miss most of the morning’s work and still be fully paid.

At eight

o’clock Linda calls Mr Donnelly on the farm to let him know that the morning’s

acupuncture session is so oversubscribed (two regular applicants, one from

education and one unemployed) so she’ll take the eight from the farm at four

o’clock this afternoon. This means that they’ll have to complete their day’s

work before reporting to the hospital. It will be interesting to see how many

of them turn up.

Young Ron (both

legs broken) hobbles in to see the doctor. He’s on the paper chase and has to

be cleared as fit and free of any problems before he can be released at 8 am

tomorrow. After the hospital, he still has to visit the gym, stores, SMU,

education, unit office and reception. How will they go about signing out a man

with two broken legs as fit to face the world? Linda comes to the rescue,

phones each department and then signs on their behalf. Problem solved.

When Dr Walling

has finished ministering to his patients, he joins me in the ward. We discuss

the drug problem in Boston, sleepy Boston,

(

population

of around 54,000).

Recently Dr

Walling’s car was broken into.

All the usual

things were stolen – radio, tapes, briefcase – but he was devastated by the

loss of a box of photographic slides that he has built up over a period of thirty

years.

Because he

hadn’t duplicated them, they were irreplaceable, and the theft took place only

days before he was due to deliver a series of lectures in America. Assuming

that it was a drug-related theft (cash needed for a quick fix), Dr Walling visited

the houses of Boston’s three established drug barons. He left a note saying

that he needed the slides urgently and would pay a reward of £100 if they were

returned.

The slides

turned up the following day.

The true

significance of this tale is that a leading doctor knows who the town’s drug

barons are, and yet the police seem powerless to put such men behind bars. Dr

Walling explains that it’s the old problem of ‘Mr Big’ never getting his hands

dirty. He arranges for the drugs to be smuggled into the country before being

sold to a dealer. Mr Big also employs runners to distribute the drugs, free of

charge, mainly to children as they leave school unaccompanied, so that long

before they reach university or take a job, they’re hooked. And that, I repeat,

is in Boston, not Chelsea or Brixton.

What will

Britain be like in ten years’ time, twenty years, thirty, if the police

estimate that 40 per cent of all crime

today

is drug-related?

No one from the

farm turns up for acupuncture.

Carl rushes in,

breathless, to say a prisoner has collapsed on the south block. Linda went home

two hours ago, so I run out of the hospital, to find Mr Belford and Mr Harman a

few yards ahead of me.

When we arrive

at the prisoner’s door, we find the inmate gasping for breath. I recognize him

immediately from his visit to Dr Walling this morning. I feel helpless as he

lies doubled-

up,

clutching his stomach, but

fortunately an ambulance arrives within minutes. A paramedic places a mask over

the inmate’s face, and then asks him some routine questions, all of which I am

able to answer on his behalf – name off doctor, last visit to surgery, nature

of complaint and medication given. I’m also able to tell them his blood

pressure, 145/78. They rush him to the Pilgrim Hospital, and as he failed his

recent risk assessment, Mr Harman has to travel with him.

As Mr Harman is

now off the manifest, we are probably down to five officers on duty tonight, to

watch over 211 prisoners.

I finish

editing

Belmarsh

, and post it back to

my publishers.

I leave the

hospital to carry out my morning rounds. This has three purposes: first, to let

each department head know which inmates are off work, second, in case of a

fire, to identify who is where, and third, if someone fails to show up for

roll-call, to check if they’ve absconded.

En route to the

farm I bump into Blossom, who had one of the pigs named after him.

(See photo page

193.) Blossom is a traveller, or a gipsy as we used to describe them before it

became politically incorrect. Blossom tells me that he’s just dug a lamb out of

the ice. It seems it got its hindquarters stuck in some mud which froze

overnight, so the poor animal couldn’t move.

‘You’ve saved

the animal’s life,’ I tell Blossom.

‘No,’ he says,

‘he’s going to be slaughtered today, so he’ll soon be on the menu as frozen

cutlets.’

I pick up my

post from the south block. Although most of the messages continue along the

same theme, one, sent from a Frank and Lurline in Wynnum, Australia is worthy

of a mention, if only because of the envelope. It was addressed thus:

Lord Jeffrey

Archer Jailed for telling a fib

Somewhere

in England.

It is dated

Christmas Day, and has taken only nine days to reach me in deepest

Lincolnshire.

The main

administration block has been sealed off. Gail tells me that she can’t get into

the building to carry out any paperwork and she doesn’t know why. This is only

interesting because it’s an area that is off-limits to inmates.

Over the past

few months, money and valuables have gone missing. Mr Berlyn is determined to

catch the culprit. It turns out to be a fruitless exercise, because, despite a

thorough search, the £20 that was stolen from someone’s purse doesn’t

materialize.

Mr Hocking, the

security officer in charge of the operation, found the whole exercise

distasteful as it involved investigating his colleagues. I have a feeling he

knows who the guilty party is, but certainly isn’t going to tell me. My deep

throat, a prisoner of long standing, tells me the name of the suspect. For

those readers with the mind of a detective, she doesn’t get a mention in this

diary.

7.30 am

A prisoner from

the south block checks into surgery with a groin injury. Linda is sufficiently

worried about his condition to have him taken to the local hospital without

delay.

Meanwhile she

dresses his wounds and gives him some painkillers. He never once says please or

thank

you. This attitude would be true of over half

the inmates, and nearer 70 per cent of those under thirty. Although it’s a

generalization, I have become aware that those without manners are also the

work shy amongst the prison population.

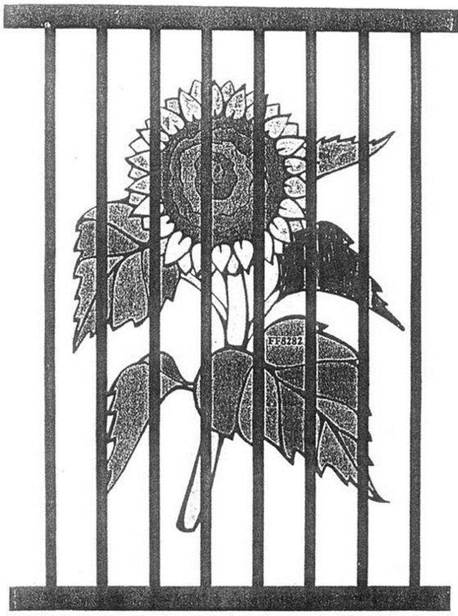

Among the

thousands of letters I’ve received since I’ve been incarcerated, several are from

charities that continue to ask for donations, signed books and memorabilia, and

occasionally for a doodle, drawing, poem or even a painting. Despite my

life-long love of art, the good Lord decided to place a pen in my hand, not a

paintbrush. But I found an alternative when I came across Darren, an education

orderly. Darren has already designed several imaginative posters and signs for

the hospital. The latest charity request is that I should produce a sunflower,

in any medium

. I came up with an idea which

Darren produces. (See overleaf.)