Heaven: A Prison Diary (19 page)

Read Heaven: A Prison Diary Online

Authors: Jeffrey Archer

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous

Incidentally,

the other gym orderly Bell is also the NSC goalkeeper. He used to be at Spring

Hill, but asked for a transfer to be nearer his wife. NSC needed a goalkeeper,

so the transfer only took four days. Thanks to this little piece of subterfuge

we’re now on a winning streak. However, I have to report that the goalkeeper’s

wife has run off with his best friend, which may account for Bell being sent

off last week. We lost 5-0.

7.30 am

I now have to

work seven days a week, as there’s a surgery on Saturday and Sunday.

It’s a small price

to pay for all the other privileges of being hospital orderly.

Not many

patients today, eleven in all, but then there’s no work to skive off on a

Saturday morning. Sister leaves at ten-thirty and I have the rest of the day to

myself, unless there’s an emergency.

Spend a couple

of hours editing

Sons of Fortune

, and

only take breaks for lunch, and later to watch the prison football match.

The football

manager and coach is a senior officer called Mr Masters. He’s proud of his

team, but when it comes to abusing the referee, he’s as bad as any other

football fan.

Today he’s

linesman, and should be supporting the ref, not to mention the other linesman.

But both receive a tirade of abuse, as Mr Masters feels able to give his

opinion on an offside decision even though he’s a hundred yards away from the

offence, and the linesman on the other side of the pitch is standing opposite

the offending player. To be fair, his enthusiasm rubs off on the rest of the

team, and we win a scrappy game 2-0.

7.30 am

Only five

inmates turn up for early morning surgery. Linda explains that although the

prison has a photographic club, woodwork shop, library, gym and chapel, a lot

of the prisoners spend the weekend in bed, rising only to eat or watch a

football match on TV.

It seems such a

waste of their lives.

My visitors

today are Malcolm and Edith Rifkind. Malcolm and I entered the House around the

same time, and have remained friends ever since. Malcolm is one of those rare animals

in politics who has few enemies.

He was

Secretary of State for Defence and Foreign Secretary under John Major, and I

can’t help reflecting how no profession other than politics happily divests

itself of its most able people when they are at their peak. It’s the equivalent

of dropping Beckham or Wilkinson at the age of twenty-five. Still, that’s the

prerogative of the electorate, and one of the few disadvantages of living in a

democracy.

Malcolm and his

wife Edith want to know all about prison life, while I wish to hear all the

latest gossip from Westminster. Malcolm makes one political comment that will

remain fixed in my memory: ‘If in 1979 the electorate had offered us a contract

for eighteen years, we would have happily signed it, so we can’t complain if we

now have to spend a few years in the wilderness.’ He and Edith have travelled

up from London to see me, and they will now drive on to Edinburgh. I cannot

emphasize often enough how much I appreciate the kindness of friends.

Mr Baker drops

in for coffee and a chat. The officers’ mess is closed over the weekend, so the

hospital is the natural pit stop. He tells me that one prisoner has absconded,

while another, on returning from his town visit, was so drunk that he had to be

helped out of his wife’s car. That will be his last town visit for several

months. And here’s the rub, it was his first day out of prison for six years.

8.50 am

‘Papa to Hotel,

Papa to Hotel, how do you read me?’

This is PO

New’s call sign to Linda, and I’m bound to say that the hospital is the nearest

I’m going to get to a hotel while I remain incarcerated in one of Her Majesty’s

establishments.

It’s a freezing

morning in this flat, open part of Lincolnshire, so there’s a long queue for

the doctor. First in line are those on the paper chase, due for release

tomorrow. The second group comprises those facing adjudication – one caught

injecting heroin, a second in possession of money (£20) and finally the inmate

who came back drunk last night. The doctor declares all three fit, and can see

no medical reason that might be used as mitigating circumstances in their

defence.

The heroin

addict is subsequently transferred back to Lincoln. The prisoner found with £20

in his room claims that he just forgot to hand it in when he returned from a

town visit, so ends up with seven days added.

The drunk gets

twenty-one days added to his sentence, and no further town visits until further

notice. He is also warned that next time,

it’s

back to

a B-cat.

Those in the

third group – by far the largest – are either genuinely ill or don’t feel like

working on the farm at below-zero temperatures. Most are told to return to work

immediately or they will be put on report and come up in front of the governor.

I phone Mary,

who has some interesting news. I feel I should point out that Mr Justice Potts

claimed at the end of my trial that this is, ‘

As

serious an offence of perjury as I have had experience of and as I have been

able to find in the books’.

A Reader in Law

at the University of Buckingham has been checking sentencing for those

convicted of perjury. She has discovered that, in the period 1991–2000,

1,024 people

were charged with this offence in the United Kingdom. Of the 830 convicted,

just

under

400 received no custodial sentence at all,

while in the case of 410, the sentence was eighteen months or less. Only four

people were given a four-year sentence upheld on appeal. One of these framed an

innocent man, who served thirty-one months of a seventeen year sentence for a

crime he did not commit; the second stood trial twice for a murder of which he

was acquitted, but was later convicted of perjury during those trials. The

other two were for false declarations related to marriage as part of a largescale

immigration racket.

There’s a knock

on my door, and as the hospital is out of bounds after six o’clock unless it’s

an emergency, I assume it’s an officer. It isn’t. It’s a jolly West Indian

called Wright.

He’s always

cheerful, and never complains about anything except the weather.

‘Hi, Jeff, I

think I’ve broken my finger.’

I study his

hand as if I had more than a first-aid badge from my days as a Boy Scout in the

1950s. I suggest we visit his unit officer. Mr Cole is unsympathetic, but

finally agrees Wright should be taken to the Pilgrim Hospital. Wright reports

back an hour later with his finger in a splint.

‘By the way,’ I

ask, ‘how did you break your finger?’

‘Slammed it in

a door, didn’t I.’

‘Strange,’ I

say, ‘because I think I’ve just seen the door walking around, and it’s got a

black eye.’

10.00 am

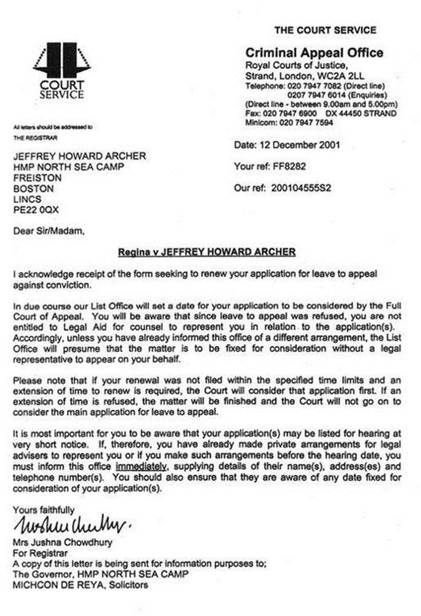

In my mailbag

is a registered letter from the court of appeal. I print it in full. (See

overleaf.) The prison authorities or the courts seem to have been dilatory, as

my appeal may be put off until February, rather than held in December. The

experts on the subject of appeals, and by that I mean my fellow

inmates,

tell me that the usual period of time between

receiving the above letter and learning the date of one’s appeal is around

three weeks. It’s then another ten days before the appeal itself.

Among my other

letters is one from Dame Edna, enquiring about the dress code when she visits

NSC.

Brian (attempt

to defraud an ostrich company) thanks me for a box of new paperbacks that have

arrived at the Red Cross office in Boston, sent by my publisher.

My new job as

hospital orderly means I’ve had to adjust my writing regime. I now write

between the hours of 6 and 7 am, 1 and 3 pm, and 5 and 7 pm. During the weekends,

I can fit in an extra hour each day, which means I’m currently managing about

thirty-seven hours of writing a week.

I visit the

canteen to purchase soap, razor blades, chocolate, Evian and phonecards,

otherwise I’ll be dirty, unshaven, unfed and unwatered over Christmas, not to

mention uncontactable. The officer on duty checks my balance, and finds I’m

only £1.20 in credit.

Help!

9.00 am

‘Archer to report to reception immediately, Archer to report to reception

immediately.’

Now Mr Daff has

retired, I’m not allowed the same amount of latitude as in the past.

I’ve received

five parcels today. The first is a book by Iris Murdoch,

The Sea,

The

Sea,

kindly sent in by a lady

from Dumfries. As I read it some years ago when Ms Murdoch won the Booker

Prize, I donate it to the library. The second is a silver bottle opener – not

much use to an inmate as we’re not allowed to drink – but a kind gesture

nevertheless. I ask if I can give it to Linda. No, but it can be put in the

old-age pensioners’ raffle.

The third is a

Parker pen. Can I give it to Linda? No, but it can be put in the old-age

pensioners’ raffle. The fourth is a teddy bear from Dorset. I don’t bother to

ask, I just agree to donate it to the old-age pensioners’ raffle. The fifth is

a large tube, which, when opened, reveals fifteen posters from the Chris

Beetles Gallery, which I’ve been eagerly awaiting for over a week. I explain

that it’s a gift to the hospital, so there’s no point in putting it in store

for me because the hospital will get it just as soon as I am released. This

time

they

agree to let me take it

away. Result: one out of five.

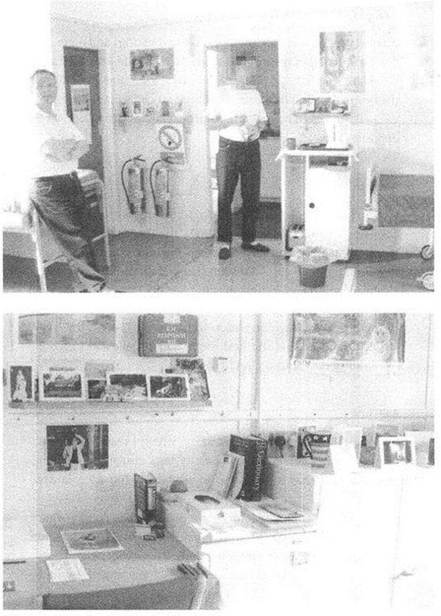

I happily spend

a couple of hours, assisted by Carl and a box of Blu-Tack, fixing prints by

Albert Goodwin, Ronald Searle, Heath Robinson, Emmett, Geraldine Girvan, Paul

Riley and Ray Ellis to the hospital walls.

With over 900

Christmas cards littered around the beds, the ward has been transformed into an

art gallery. (See opposite.)

I return to the

canteen. I’m only £2.50 in credit, whereas I calculate I should have around

£18. It’s the nearest I get to losing my temper, and it’s only when the officer

in charge says he’s been trying to get the system changed for the past year

that I calm down, remembering that it’s not his fault. He makes a note of the

discrepancy on the computer. I thank him and return to the hospital.

I have no

reason to complain; I’ve got the best job in the prison and the best room, and

am allowed to write five hours a day.

Shut up, Archer.

I attend the

carol service at six-thirty, where I read one of the lessons. Luke 2, verses

eight to twenty. As I dislike the modern text, the vicar has allowed me to read

from the King James

version

.

The chapel is

packed long before the service is due to begin and the organ is played with

great verve and considerable improvisation by Brian (ostrich fraud). The

vicar’s wife, three officers and four inmates read the lessons. I follow Mr

New, and Mr Hughes follows me. We all enjoy a relaxed service of carols and

lessons, and afterwards there is the added bonus of mince pies and coffee,

which might explain the large turnout.

After the

service, Brian introduces me to Maria, who’s in charge of the Red Cross shop in

Boston. She has brought along my box of paperbacks and asks if I would be

willing to sign them. I happily agree.

7.30 am

Record numbers

report sick with near freezing conditions outside.