Heaven: A Prison Diary (25 page)

Read Heaven: A Prison Diary Online

Authors: Jeffrey Archer

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous

2.00 pm

I was hoping to

see Mary, Will and James today, but the authorities have decreed that I’ve used

up all my visits for this month, and therefore can’t see them until the

beginning of February.

This week’s

football match has also been cancelled, so once again I come face to face with

the prisoner’s biggest enemy, boredom.

10.51 am

Mr Hart (an

old-fashioned socialist) visits the hospital to tell me that there’s a

doublepage spread about me in the

News of

the World

. It seems that Eamon (one of the Derby Five) is the latest former

inmate to take his thirty pieces of silver and tell the world what it’s like to

share a room with Jeff.

I am surprised

how many prisoners visit me today to tell me what they think of Eamon. Strange

phrases like ‘broken the code’,

‘

not

the done thing’ come from men who are in for murder and

GBH. After Belmarsh, Fletch, Tony, Del Boy and Billy said nothing, while

Darren, Jimmy, Jules and Sketch from Wayland also kept their counsel. Here at

NSC, I trust Doug, Carl, Jim, Clive and Matthew. And they would have stories to

tell.

I’ve started a

prison tea club as I love to entertain whatever the circumstances. Admittedly

it would have been impossible at Belmarsh or Wayland, but as I now reside in

the hospital, I am even able to send out invitations. Membership is confined to

those over the age of forty.

My guests are

invited to attend ‘Club Hospital’ on Sunday between the hours of 4 pm and 6 pm.

They will be served tea, coffee, biscuits and scones supplied by Linda. The

current membership is around a dozen, and includes David (fraud, schoolmaster),

John (fraud, accountant), John (fraud, businessman), Keith (knowingly in

possession of drugs), Brian (ostrich farm and chapel organist), Doug (importing

cigarettes), the Major (stabbed his wife), the Captain (theft, drummed out of

the regiment), Malcolm (fraud) and Carl (fraud).

The talk is not

of prison life, but what’s going on in the outside world. Whether the IRA

should be given rooms in Parliament, whether Bin Laden is dead or alive, the

state of the NHS and the latest from the Test Match in India. All of my guests

keep to the club rules.

They remove their

shoes and put on slippers as they enter the hospital, and no smoking or

swearing is tolerated. Two of them will be leaving us next week, Keith will

have served five years, and Brian nearly three. We raise a cup to them and wish

them luck. Carl and David stay behind to help me with the washing-up.

730 am

I’m becoming

aware of the hospital regulars: five prisoners who turn up every morning

between 7.30 and 8 am to collect their medication. I couldn’t work out why

these five need the same medication for something most of us would recover from

in a few days.

Sister has her

suspicions, but if a prisoner complains of toothache, muscle sprain or

arthritis, they are entitled to medications that are opiate based – for example

codeine, co-codamol or dextropropoxyphene. These will show up as positive on

any drugs test, and if a prisoner has been on them every day for a month, they

can then claim, ‘It’s my medication, guv.’ However, if an inmate tests positive

for heroin, the hospital will take a blood sample and seek medical advice as to

whether his daily medication would have registered that high. Several prisoners

have discovered that such an element of doubt often works in their favour. Doug

tells me that some addicts return to their rooms, flush the pills down the

lavatory and then take their daily dose of heroin.

A lifer called

Bob (twelve years, murder) is due to appear in front of the parole board next

week. He’s coming to the end of his tariff, and the Home Office usually

recommends that the prisoner serves at least another two years before they will

consider release. This decision has recently been taken out of the hands of the

Home Office and passed to the parole board. Bob received a letter from the

board this morning informing him he will be released next Thursday.

Try to imagine

serving twelve years (think what age you were twelve years ago) and now assume

that you will have to do another two years, but then you’re told you will be

released on Thursday.

The man is walking

around in a daze, not least because he fell off a ladder yesterday and now has

his ankle in a cast. What a way to start your re-entry back to Earth.

11.00 am

Andrew Pierce

of

The Times

has got hold of the

story that Libby Purves will be interview-ing Mary tomorrow. The BBC must have

leaked it, but I can’t complain because the piece reads well, even if Mr Pierce

is under the illusion that NSC is in Cambridgeshire. I only wish it were.

Among my

afternoon post is a Valentine’s card, which is a bit like getting a Christmas

card in November, one proposal of marriage, one offer of a film part (Field

Marshall Haig), a request to front a twelve-part television series and an

invitation to give an after-dinner speech in Sydney next September. Do they

know something I don’t?

An officer

drops in from his night rounds for a coffee. He tells me an alarming story

about an event that took place at his last prison.

It’s

universally accepted among prisoners that if one particular officer has got it

in for you, there’s nothing you can do about it. You can go through the

complaints procedure, but even if you’re in the right, officers will always

back each other up if a colleague is in trouble. I could fill a book with such

instances. I have experienced this myself at such a petty level that I have not

considered the incident worth recording. On that occasion, the governor

personally apologized, but still advised me not to put in a complaint.

However, back

to a prisoner from the north block who did have the temerity to put in a

written complaint about a particular officer. On this occasion, I can only

agree with the prisoner that the officer concerned is a bully. Nevertheless,

after a lengthy enquiry (everything in prison is lengthy) the officer was

cleared of any misdemeanour, but that didn’t stop him seeking revenge.

The inmate in

question was serving a fiveyear sentence, and at the time he entered prison was

having an affair that his wife didn’t know about, and to add to the complication,

the affair was with another man.

The prisoner

would have a visit from one of them each fortnight, while writing to both of

them during the week. The rule in closed prisons is that you leave your letters

unsealed in the unit office, so they can be read by the duty officer to check

if you’re still involved in any criminal activity, or asking for drugs to be

sent in. When the prisoner left his two letters in the unit office, the officer

on duty was the same man he had made a complaint about to the governor. The

officer read both the love letters, and yes, you’ve guessed it, switched them

and sealed the envelopes and with it, the fate of the prisoner.

How do I know

this to be true? Because the officer involved has just told me, and is happy to

tell anyone he considers a threat.

9.00 am

Mary is on

Midweek

with Libby Purves.

I call Mary.

She’s off to lunch with Ken Howard RA and other artistic luminaries.

My visitors

today are Michael Portillo and Alan Jones (Australia’s John Humphreys). I must

first make my position clear on Michael’s leadership bid. I would have wanted

him to follow John Major as leader of the party. I would also have voted for

him to follow William Hague, though I would have been torn if Malcolm Rifkind

had won back his Edinburgh seat.

It is a robust

visit, and it serves to remind me how much I miss the cut and thrust of

Westminster, stuck as I am in the coldest and most remote corner of

Lincolnshire. Michael tells us about one or two changes he would have made had

he been elected leader.

We need our own

‘Clause 4’ he suggests, which Tony Blair so brilliantly turned into an

important issue, despite it being of no real significance. Michael also feels

that the party’s parliamentary candidates should be selected from the centre,

taking power away from the constituencies. It also worries him how few women

and member of minority groups end up on the Conservative benches.

He points out

that at the last election, the party only added one new woman to its ranks, at

a time when the Labour party have over fifty.

‘Not much of an

advertisement for the new, all-inclusive, modern party,’ he adds.

‘But how would

you have handled the European issue?’ ask Alan.

Michael is about

to reply when that redhot socialist (local Labour councillor) Officer Hart

tells us that our time is up.

Politics is not

so overburdened with talent that the Conservatives can survive without

Portillo, Rifkind, Hague, Clarke and Redwood, all playing important roles,

especially while we’re in opposition.

When the two

men left I was buzzing. An hour later I wanted to abscond.

I call Mary.

She has just left the chambers of Julian Malins QC, and is going to dinner with

Leo Rothschild.

8.15 am

I’m called out

of breakfast over the tannoy and instructed to return to the hospital

immediately. Five new prisoners came in last night after Gail had gone home.

She needs all the preliminaries carried out (heart rate, weight, height) before

Dr Walling arrives at nine. One of the new

intake

announces with considerable pride that although this is his fifth offence, it’s

his first visit to NSC.

Once surgery is

over, Dr Walling joins me for a coffee on the ward. ‘One of them was a

nightmare,’ he says, as if I wasn’t ‘one of them’. He doesn’t tell me which of

the twenty patients he was referring to, and I don’t enquire. However, his next

sentence did take me by surprise. ‘I needed to take a blood sample and couldn’t

find a vein in his arms or legs, so I ended up injecting his penis.

He’s not even

half your age, Jeffrey, but you’ll outlive him.’

The new vacuum

cleaner has arrived. This is a big event in my life.

I call Mary at

Grantchester. She has several pieces of news; Brian Mawhinney has received a

reply to his letter to Sir John Stevens, the commissioner of the Metropolitan

Police, asking why I lost my D-cat and was sent to Wayland. A report on the

circumstances surrounding that decision has been requested, and will be

forwarded to Brian as soon as the commissioner receives it.

Mary’s next

piece of news is devastating.

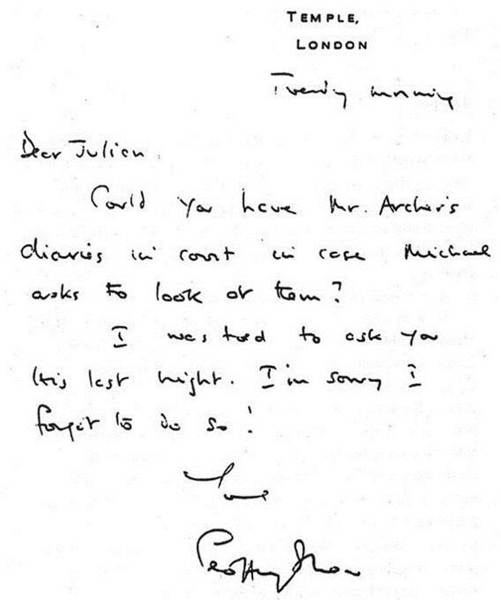

Back in 1999,

Julian Mallins had kindly sent a note he had retained in his files (see

overleaf), sent to him by Geoffrey Shaw, junior to Michael Hill for the defence

in the libel trial. In the note, Shaw asks Julian for my two diaries for 1986

(an A4 diary and an Economist diary) ‘in case Michael asks to look at them’.

Julian passed the diaries to Shaw and Hill for inspection, and told Mary he is

pretty sure that they would have gone through them thoroughly – and clearly

found nothing worthy of comment in them, since they were not an issue in the

libel trial.

Julian added

that it would be ‘absolute rubbish’ to suggest that the Star’s lawyers could

not have examined these two diaries (which Angela Peppiatt had claimed in the

criminal trial were almost entirely blank) in court for other entries.

Later Julian

wrote to Mary: ‘English law in 1986 was not an ass. If it had been Michael

Hill’s suggestion that the alibi evidence was all true, except for the date,

neither Lord Archer in the witness box nor the judge, still less Lord Alexander

nor I, could have objected to Michael Hill going through the rest of the diary

to find the same dinner date with the same companion at the same restaurant but

on another date.’

None of us had

known anything of Peppiatt’s pocket diary for 1986, in which she noted both her

own and my engagements, kept as her own property for over ten years, but

produced in court as my ‘true’ diary for that year.

Mary also tells

me that she has written to Godfrey Barker about his earlier reference to dining

with Mr Justice Potts some time before the trial, when the judge might have

made disparaging remarks about me. She now fears Godfrey will disappear the

moment the date of the appeal is announced.

10.00 am

I weigh myself.

Yuk. I’m fourteen stone two pounds. Yuk. I lost eleven pounds during my three

weeks at Belmarsh, falling to twelve stone seven pounds. At Wayland I put

that

eleven pounds back on in ten weeks, despite being in

the gym every day. At NSC the food is better, but because of my job I don’t

have time to go to the gym (poor excuse). On Monday I must stop eating

chocolate and return to the gym. I am determined to leave the prison, whenever,

around twelve stone eight pounds.