Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (10 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

If indeed Millet noted other gay men among the travelers on the

Titanic

, who might they have been? One passenger often thought to be gay was a good-looking, thirty-five-year-old rubber merchant from Liverpool named Joseph Fynney. He was active in youth work at his local church, and the late-night visits of adolescent boys to his home raised the suspicions of neighbors that he was “

a Nancy boy.” Fynney visited his widowed mother in Montreal yearly and usually brought along a teenaged boy for the trip. This time his companion was a dark-haired, sixteen-year-old barrel maker’s apprentice named Alfred Gaskell. Both Fynney and Gaskell, however, were traveling in second class and so would not likely have been seen by Millet during the brief time he had been on the ship.

During the long wait on the tender, however, Frank Millet would probably have noticed a handsome Egyptian manservant who was traveling with Henry and Myra Harper (and their Pekingese). Millet may have been acquainted with Henry Harper, since he was a good friend of his more dynamic cousin, Harry Harper, and had done work for the family’s magazines in New York City. Henry Sleeper Harper would later write that the Egyptian manservant was “

an old dragoman [guide] of mine who had come with me from Alexandria because he wanted ‘to see the country all the crazy Americans came from.’ ” But Hammad Hassab was actually a young, unmarried dragoman of striking good looks, and despite the fashion for having exotic servants, his presence with the Harpers had a whiff of impropriety to it.

A trio of Canadian bachelors who were known as “the Three Musketeers” could also possibly have drawn Millet’s attention, although he would have spotted only two of them, Thomson Beattie and Thomas McCaffry, since their traveling companion, John Hugo Ross, was ill and confined to his cabin. Ross and Beattie were both successful real estate agents in Winnipeg, Manitoba, then a boomtown with Canada’s largest per capita population of millionaires. To escape the fierce prairie winters, Beattie and his close friend McCaffry, a Vancouver banker, were in the habit of boarding liners for destinations like North Africa or the Aegean. This year, they had been joined by Ross, another dapper, witty bachelor, and the three men had departed from New York in January bound for Trieste and a three-month tour of Italy, Egypt, France, and England. After two months of travel, Ross had fallen ill with dysentery in Egypt and his travel-weary companions had become anxious to get home. Beattie had written from Paris to his mother in Fergus, Ontario: “

We are changing ships and coming home in a new, unsinkable boat.” The usually energetic Ross was so frail he had to be carried aboard the

Titanic

in Southampton and spent the rest of the voyage in his cabin. Beattie and McCaffry, whom the

Winnipeg Free Press

would describe as “

almost inseparable,” shared cabin C-6, a room with a large window that looked out on the forward well deck.

Though bachelorhood, it must be noted, is not necessarily an indicator of homosexuality, it took considerable resilience to remain single in an era when marriage bestowed manhood. For lesbians the social pressure was less intense since “maiden ladies” living together drew little scrutiny. In America, these alliances between women were sometimes known as “Boston marriages,” a term coined from Henry James’s 1886 novel

The Bostonians

, which described two “new women” living together in a marriage-like relationship. If Frank had observed the portly and mannish Ella White gesturing with her walking stick to her soft-spoken younger companion, Marie Young, on the

Nomadic

, he may have suspected that the two women had such a relationship. Some “Boston marriages” were platonic, however, and it is not known if there was a sexual component to Ella White’s relationship with Marie Young. But the two women lived and traveled together for thirty years, and when Ella White died in 1942, the bulk of her estate was left to Marie Young.

We also cannot know whether Frank’s closeness to Archie Butt ever extended beyond the bounds of mere friendship. Archie was far too careful to ever pen anything as indiscreet as Millet’s correspondence with Stoddard. Yet within Archie’s letters there are enough clues to picture him as a Ragtime-era gay man hiding in plain sight. Archie had the same gift for observation and waspish wit found in gay diarists from Horace Walpole and Henry “Chips” Channon to Cecil Beaton and Andy Warhol. He also had a remarkable eye for the details of women’s clothes and jewelry and could, for example, describe from memory a selection of First Lady Edith Roosevelt’s gowns and include such details as “

black velvet with

passementerie

down the front.”

Archie also remarks often on the “

pulchritude of the male element” he sees at social gatherings, employing expressions like “

as handsome as a young Greek athlete.” And although Archie was often named as one of Washington’s most eligible bachelors, he was unable to sustain a relationship with any woman other than his mother. To modern eyes, Archie’s attachment to Pamela Boggs Butt seems extreme. During his three-year posting in the Philippines, he had pined so much for her that he had arranged to bring her halfway across the world—into a war zone—for an extended visit. Pamela then lived with him when he returned to Washington as depot quartermaster and joined him in Cuba when he was posted there in 1905. Even years after her death Archie thought of his mother daily, surrounded by photographs and mementoes of her.

On the first day of May 1911, Archie wrote that a certain woman “

has been camping on my trail for many months now” but then notes that he will not marry her because he is sure he could not love her and “I don’t think that my mother would have liked her at all.” He then describes the only two women he ever really loved. The first was a girl who had been fond of him when he was in his early twenties but her “cat of a mother” was determined that she should marry a rich man. The second was Mathilde Townsend, the now-married daughter of one of Washington’s leading hostesses, who, as he notes, “never really cared for me, not in the way of love.” Yet when Mathilde had told Archie in early April of 1910 that she was engaged to someone else, he wrote to Clara that it was “

a terrific blow to me … and [I] woke this morning as if someone had died in the night.”

Archie’s distress over losing Mathilde seems a trifle overdramatized given that she had done nothing to encourage his interest. After sitting out a ball with her several weeks before, Archie had recorded that “

it was the same old story at the end. An evening wasted in beating my hands against an iceberg.” Mathilde, aged twenty-four, had clearly found it awkward that dear old Archie (he was twenty years her senior) was suddenly trying to woo her. Archie also knew that Mathilde’s redoubtable mother, Mary Scott Townsend, widow to a railroad baron, had set her eye on “a coronet” [a British dukedom] for her daughter, and that an army quartermaster, his current lofty post notwithstanding, was not in the running. He sympathized with Mathilde’s resistance to becoming yet another “dollar princess”—yet his own social ambition is evident when he writes: “

I shall not mention her again, save only as one who has passed out of my life into that world of New York and Newport

into which I have peeped but will never enjoy

” [italics mine].

He does mention Mathilde again, however, since on May 26, 1910, he attended her wedding at the vast Townsend mansion on Massachusetts Avenue to see the lovely bride pass down an aisle of lilies in a white satin Worth gown with a three-yard train. By December, Archie is reporting that he had recently had “

such fun doing the shops” with Mathilde, now Mrs. Peter Gerry, followed by lunch at the Plaza. Men who are fun to go shopping with are rarely the marrying kind, yet if Archie was indeed homosexual he was likely not effeminate, since no one with any less-than-manly traits could have succeeded in the testosterone-fueled atmosphere that surrounded Theodore Roosevelt. Archie had kept up with Roosevelt in all his physical stunts, from rock climbing and fording icy streams in Rock Cliff Park to making

a strenuous one-day, ninety-eight-mile gallop to Warrenton, Virginia, and back through sleet and snow. Roosevelt was quite sensitive regarding effeminacy—he had been dubbed “

Oscar Wilde” as a young New York State assemblyman after wearing a purple suit and delivering a speech in a high-pitched voice. As president, he would never allow himself to be photographed in tennis whites—even though his inner circle was dubbed his “tennis cabinet”—preferring to release pictures in which he was posed in buckskin or on horseback.

At the end of March 1910, just before Archie received the news of Mathilde’s engagement, he wrote that Frank Millet had taken up residence at his home and that “

he is such a good housekeeper that I think I will turn the housekeeping over to him.” Frank gave English lessons to the Filipino houseboys before breakfast and, in Archie’s absence, wallpapered the second floor with rose-patterned paper that Archie claimed made him feel like Heliogabalus, the Roman emperor who smothered his guests in roses. Despite these hints of domesticity, there is no evidence that the relationship extended beyond companionship. A young naval lieutenant who roomed for a time with the two men would only remember their unusual sympathy of mind and that “

on the older man [i.e., Millet] Major Butt leaned for advice and took it.”

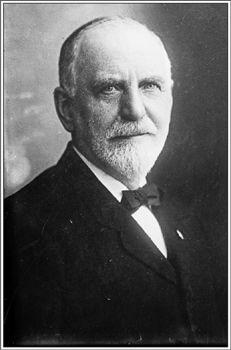

W. T. Stead

(photo credit 1.35)

AS MILLET WAS

writing about the “queer lot of people” on the

Titanic

, the man who had spurred an act of Parliament that outlawed homosexuality in Great Britain was also dashing off final notes to family and friends in his C-deck cabin. William Thomas Stead was a trailblazing investigative journalist, known to all as W. T. Stead and often hailed as “the Napoleon of newsmen.” Over the past thirty years, Stead had tackled issues that had both outraged and mobilized people in Britain and abroad. In 1890, the

New York Sun

claimed that Stead, “

between the years 1884 and 1888 came closer to governing England than any other man in the kingdom.” Over the last fifteen years, the veteran journalistic crusader had made world peace one of his causes and this had earned him a nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1903. He was now on his way to New York to give a talk on “Universal Peace” at the Men and Religion Forward Movement Congress in Carnegie Hall on April 21.

At sixty-two, Stead was three years younger than Frank Millet but looked older due to his furrowed brow and snowy Old Testament beard. The prophetic look was appropriate to another of Stead’s pursuits—communing with the spirit world. He had become the medium for a spirit named Julia, who communicated through automatic writing and séances. Stead had compiled Julia’s messages in a book entitled

After Death

and had also set up a psychic institute called Julia’s Bureau. Julia had not communicated any

Titanic

forewarnings to Stead, however, and in a letter sent at Queenstown to his daughter Estelle he enthuses about the size and magnificence of the ship and his “

love of a cabin … with a window about 4 ft. by 2 ft. looking out over the sunlit sea.” He also describes the

Titanic

as “a splendid, monstrous, floating Babylon.” The “Babylon” metaphor significantly invokes Stead’s most famous—and most notorious—journalistic campaign, a series of articles he wrote in 1885 entitled “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon.” As the editor of the London daily newspaper, the

Pall Mall Gazette

, Stead had been approached in May of 1885 by a prominent anti-vice campaigner to help rouse public opinion in support of a bill that was stalled in Parliament. The Criminal Law Amendment Act, which proposed measures to combat child prostitution and white slavery, had gone down to defeat three times in the House of Commons. The anti-vice advocate’s stirring stories of exploited children fired Stead’s reformist zeal and he plunged into an investigation of London’s seamy underworld, interviewing everyone from procurers and pimps to rescue workers and jail chaplains. He even arranged for one of his female staffers and a Salvation Army lass to pose as prostitutes and penetrate brothels, with the assumption that they could make an escape before service was required.

When the first installment of “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon” appeared on July 6, 1885, it caused a sensation. Victorian London had never seen such frank sexual content in print. Headlines like

THE VIOLATION OF VIRGINS

,

THE CONFESSIONS OF A BROTHEL-KEEPER

, and

HOW GIRLS WERE BOUGHT AND RUINED

both titillated and outraged. When W.H. Smith & Son, London’s largest distributor to newsstands, refused to sell the papers, volunteers, including members of the Salvation Army, stepped in to help. Even George Bernard Shaw telephoned with an offer of assistance. Over the next four days the

Gazette

’s offices were mobbed as crowds fought to obtain sheets still wet from the press and the police had to be called in to maintain order. Secondhand copies sold at twelve times the normal cost. Soon public meetings and angry demonstrations in support of the Criminal Law Amendment Act took place all over Britain. The Salvation Army amassed 393,000 signatures on a petition a mile and a half long and marched with it in a giant roll to Westminster under a banner saying,

[WE] DEMAND THAT INIQUITY SHALL CEASE

. Parliamentarians quickly bowed to public pressure and the CLA Act (informally dubbed “Stead’s Law”) received royal approval on August 14, with Queen Victoria noting that she “

had pleasure in giving my assent.”