Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (4 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

After five o’clock that afternoon, with the luggage loaded aboard the Cherbourg tenders, passengers began making their way toward their gangways. As Frank approached the

Nomadic

, his weary mood may have lifted. He could look forward to dining with Archie on the

Titanic

that evening and hearing his droll observations of the other passengers, all delivered in Archie’s characteristic Georgia drawl. Millet had often said that he was not a fan of maiden voyages—he preferred liners where the officers and crew were more familiar with the ship. But his meetings in America wouldn’t wait. And if White Star’s new liner lived up to its billing, there would be a comfortable room and a good dinner for him at the end of this very long day.

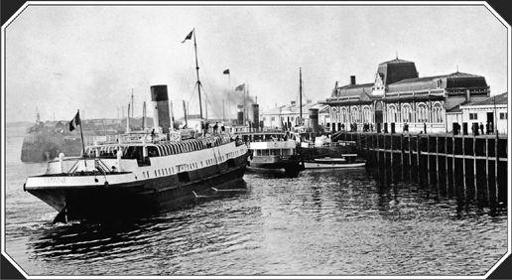

Among those boarding the tender

Nomadic

(top, at left) were John Jacob Astor, his young wife, Madeleine, and their Airedale, Kitty.

(photo credit 1.12)

A

s Nicholas Martin had promised, the tender

Nomadic

was ready for

departure at 5:30. Although the

Titanic

had still not been sighted, Martin had decided to board the passengers and have the tender wait in the harbor. With a late-afternoon chill now in the air, most of the

Nomadic

’s 172 first- and second-class passengers made their way down to the lounge, where roll-backed slatted benches provided plenty of seating. The room was paneled in white and decorated with carved ribbon garlands that gave a hint of the elegance awaiting on the

Titanic

. By contrast, the

Traffic

, now loaded with mailbags and the wicker cases and satchels of steerage travelers, had clean but spartan interiors, in the style of White Star’s third-class accommodations.

Soon the floor of the

Nomadic

’s lounge began to vibrate and smoke belched from its single stack as the tender started to move toward the breakwater. It wasn’t long, however, before the young American R. Norris Williams began to wonder why they had been sent out on the tender so soon. “

Riding the waves in the outer harbor is interesting for a little while,” he noted, “but then you get bored; the saloon is stuffy so you wander the decks again, just waiting. Innumerable false alarms as to the sighting of the

Titanic

—more waiting—slight and passing interest in a fishing boat—more waiting.” Williams had spotted one of his idols, the U.S. tennis star Karl H. Behr, among the Cherbourg passengers. Behr, aged twenty-six, had been ranked as the number 3 player in the United States and had competed for the Davis Cup and at Wimbledon. Norris Williams was a talented player himself who had won championships in Switzerland and France and was planning to play on the U.S. tennis circuit that summer before entering Harvard in the fall. He was traveling with his father, Charles Williams, who was originally from Philadelphia and was, in fact, a great-great-grandson of the most famous of all Philadelphians, Benjamin Franklin. Williams Senior had practiced law in Philadelphia before moving to Geneva with his wife in the late 1880s. Norris had been born and educated there and was fluent in three languages as a result. At twenty-one, he was tall and lanky, with prominent ears and a winning smile seen above the broad collar of his fur coat. Father and son were both wearing large fur coats, which would have caught the eye of Frank Millet as he scanned the room for people he knew.

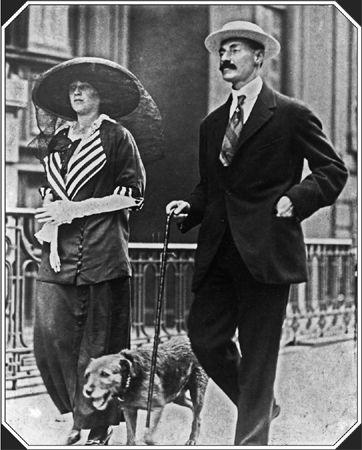

R. Norris Williams and his father, Charles Williams

(photo credit 1.25)

The Astors with their entourage and Airedale terrier stood out as well. Even their Airedale, named Kitty, had become famous, from the many photographs of the couple with the dog that had been splashed in the newspapers the summer before. Everything the Astors did was news, but the fact that forty-seven-year-old John Jacob Astor IV, whom the gossip sheets preferred to call Jack Astor, or even Jack-Ass (tor), was engaged to a teenaged girl almost thirty years his junior had provided the year’s juiciest story. Every detail of the romance had fueled daily headlines. When they would wed and where was a subject of heated speculation. Astor had confessed to adultery in late 1909 in order to grant his first wife the divorce she so ardently desired. This had eased the case through the courts but had greatly lowered his chances for church-sanctioned second nuptials.

Jack Astor’s first marriage, to the Philadelphia society beauty Ava Lowle Willing, had been a disaster from the start. The night before the lavish wedding in February of 1891, the tearful bride-to-be had purportedly begged her parents to call it off. Marrying into America’s richest family was clearly not enough to overcome the fact that at twenty-six, Jack Astor was already earning his jackass sobriquet. Within his circle he had a reputation for “

pawing every girl in sight,” and in 1888 a gossip column had gleefully described him brawling with another young preppy—using both fists and walking sticks—in the cloakroom of Sherry’s Restaurant. The fight, unsurprisingly, had been over a girl.

Tall and awkward, with a large head atop a skinny frame, Astor had grown up being cosseted by a domineering mother and four older sisters and ignored by a distant and dissipated father. Boarding school at St. Paul’s in New Hampshire was followed by three years of studying science at Harvard, where he left without finishing his degree. “

It is very questionable, whether, were he put to it, he could ever earn his bread by his brains,” was the observation of the Manhattan gossip sheet

Town Topics

. But Jack was clever with machines and spent many hours tinkering in his home laboratory dreaming up new inventions. Many of these were highly impractical, but a “

pneumatic road improver” that could suck up dirt and horse droppings from city streets had won him a prize at the 1893 Chicago Exposition. The next year, he had published a Jules Verne–ish novel,

A Journey in Other Worlds

, which envisioned electric cars and space travel in the year 2000.

Within a year of their wedding, the beautiful Ava (pronounced

Ah-vah

) had dutifully produced a son, William Vincent Astor, but from then on she ignored her husband as much as she could, devoting herself to parties, bridge, and flirtations. (A daughter, Alice, born in 1902, was rumored not to be Astor’s child.) Divorce was out of the question as long as Jack’s mother, Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, was alive. The Schermerhorns had been early Dutch settlers in the Hudson Valley, and it was this lineage, coupled with her husband’s vast fortune, that allowed Caroline Astor to appoint herself queen of New York society. Her annual ball was the city’s most exclusive affair, and a divorce could cause exclusion from its gilded guest list. The name “the Four Hundred,” for the city’s social elite, was believed to refer to the capacity of Mrs. Astor’s ballroom, but it was, in fact, Mrs. Astor’s chief courtier, a drawling socialite named Ward McAllister, who had coined the term when asked by a reporter how many people he thought comprised New York society. McAllister had realized that greater status than his means allowed could come from organizing the society of a city awash in new money. And he soon saw that Caroline Astor, whom he dubbed the “Mystic Rose” after the heavenly being in Dante’s

Paradiso

, around whom all others revolve, was in need of a court chamberlain.

When the Mystic Rose gave a ball, her Fifth Avenue mansion was decorated with hundreds of American Beauty roses and she appeared festooned in so many diamonds that her court jester, the outrageous Harry Lehr, called her “

a walking chandelier.” Yet by the early years of the new century the New York/Newport social set was growing tired of Mrs. Astor’s stiffly elegant gatherings. When a stroke diminished her faculties in 1905, Caroline Astor became a recluse, inspiring a depiction in the Edith Wharton story “After Holbein” in which “

the poor old lady who was gently dying of softening of the brain … still came down every evening to her great shrouded drawing-rooms with her tiara askew on her purple wig, to receive a stream of imaginary guests.”

The death of

the

Mrs. Astor in 1908 marked the end of an era in New York society, but it also provided an opportunity for her son and his wife to end their moribund union. The next year, after the most discreet divorce that money could buy became final, Ava boarded the

Lusitania

for England, where she was well known in society. She eventually married an English baron, Lord Ribblesdale, and although the marriage did not last, Ava remained Lady Ribblesdale for life.

Freed from the shadow of two overbearing women, Jack soon demonstrated an uncharacteristic bonhomie. Formerly glum and awkward at social gatherings, he now accepted invitations readily and hosted parties at Beechwood, the thirty-nine-room family “cottage” in Newport, and at the Fifth Avenue Astor mansion. While visiting Bar Harbor in the summer of 1910, he met a seventeen-year-old girl named Madeleine Talmage Force and became instantly smitten. Madeleine and her formidable mother (known in society as “

La Force Majeure

”) were soon regular guests on Astor’s yacht

Noma

, in his box at the opera, at Beechwood in Newport, at Ferncliff, his Hudson Valley estate, as well as at the Manhattan mansion. All of which must have dazzled a teenager just out of Miss Spence’s School for Girls.

Early in 1911,

Town Topics

noted that “

Mother Force has let no grass grow in getting her hook on the Colonel [Astor].” By August 2, the

New York Times

had reported that the couple were engaged and described how this had come about. Madeleine’s father, apparently concerned about “

continued rumors of the attachment between Colonel Astor and his daughter,” had called Astor on the telephone to discuss the matter and it had been agreed that Father Force should announce the engagement.

Force majeure

, indeed.

Over the next five weeks, the newspapers feasted on wedding details, particularly as one minister after another refused to officiate. In the end, a Congregationalist pastor presided over a rather short service held in the ballroom at Beechwood in Newport on September 9, 1911. Criticism from the pastor’s congregation would soon cause his resignation from the ministry. The newlyweds, too, received a very cool reception from Astor’s social set, which may have contributed to their decision to leave in January for a ten-week Mediterranean tour highlighted by a trip down the Nile.