American Tempest (28 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

Early in March sixty Boston Mohawks reprised the Tea Party by boarding the

Fortune

, forcing the crew below, and dumping nearly thirty chests of tea (about one hundred pounds per chest) into the bay. The second Boston Tea Party combined with the arrival of fine spring weather to infect Americans with Tea Party fever. In town after town, ordinarily law-abiding citizensâ

some dressed as Indians, others as Redcoatsâmarched merrily through the streets, mocking, flaunting, and taunting British authorities and soldiers and, wherever they could, dumping or burning tea. A mob disguised as Indians boarded a tea ship in New York in March and dumped its entire cargo into the water. In April a tea ship tied up in Annapolis with two thousand pounds of tea aboard, only to a have a mob set fire to it and destroy its cargo.

“I think, sir, I went to Annapolis yesterday to see my liberty destroyed,” declared Joseph Galloway, the thoughtful speaker of the Maryland Assembly. Although he sided with protesters who claimed that Parliament had no constitutional right to tax colonists, he believed deeply that Britain had a lawful right to legislate for the American colonies and refused to countenance breaking the law or consider any but peaceful solutions to the conflict over taxation.

A ship attempting to land tea in Greenwich, New Jersey, met the same fate as the one in Annapolis. In June the

Grosvenor

sailed into Portsmouth, New Hampshire, with twenty-seven chests of tea. A mob of less strident

Patriots convinced the owner to order the ship to come about and head for Halifax. But when the same ship owner tried to land another thirty chests in September, the mob lost patience and all but destroyed his house.

Unfortunately, England's leaders continued to miscalculate the depth of colonial resentment toward British attempts to tax themâand the growing unity that the Tea Party was slowly provoking beyond Boston. Misinterpreting the Tea Party as an isolated criminal enterprise, the British ministry focused its efforts on crushing Boston and bringing its rebel chiefs to the gallows. Although formal arrest orders for Hancock and Adams would not reach Massachusetts for several weeks, Adams acted in kind by demanding that the Massachusetts House of Representatives impeach Chief Justice Peter Oliver for accepting his salary from King George instead of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. The House voted overwhelmingly in favor of impeachment, ninety-two to eight, but before the trial could begin, Governor Hutchinson adjourned the General Court. Uncertain how to respond,

the Boston Town Meeting turned to John Hancock, inviting him to address them as Massacre Day orator on March 4.

On the eve of Hancock's speech, Andrew Oliver, the chief justice's older brother and the merchant whom the mob had twice humiliated at the Liberty Tree, diedâa broken man. “The indignities offered him,” his friend Governor Thomas Hutchinson lamented, “sunk his spirits, and he . . . at last left us suddenly. . . . The lieutenant governor is out of the reach of the malice of his enemies. They followed him, however, to the grave; a part of the mob . . . upon the relations coming out of the burying ground, giving three huzzas, and yet few better men have lived.”

13

Mob threats prevented Andrew's brother Peter Oliver from making a

final visit to the death bed of an only living brother. . . . The risk of his life was too great for him . . . and his friends advised him not to pay his fraternal respect to his brother's obsequies. The advice was just, for it afterwards appeared that had he done so, it was not probable that he ever would have returned to his own home. Never did cannibals thirst stronger for human blood than the adherents to this faction. Humanity seemed abhorrent to their nature.

Mourners at the funeral later confirmed that a mob had indeed insulted them and interrupted the solemnity of the services.

14

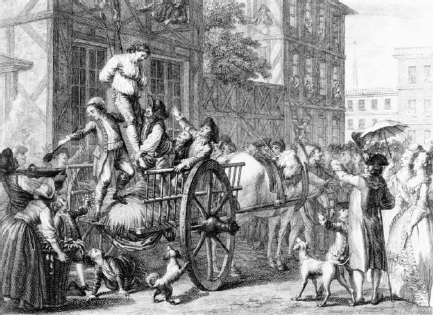

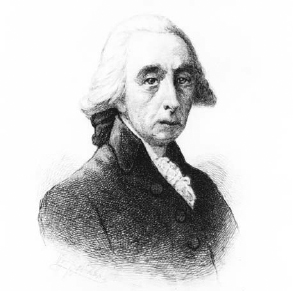

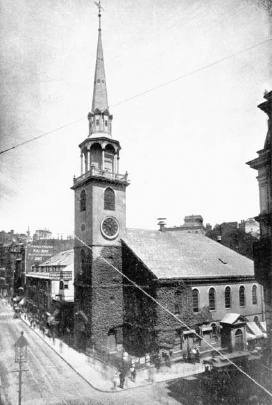

Massacre Day fell on a SaturdayâMarket Dayâand the crowds were larger than expected. For most Americans, oratory was a principal form of entertainment, and the Market Day crowds and the curious joined Patriots from Boston and outlying areas flocking to Faneuil Hall to hear the merchant-king-turned-Patriot. The larger-than-expected crowd forced organizers to move the meeting to Old South Meeting House. Still, they filled every pew, every inch of space along the aisles, in the galleries and stairways, and even the outer hall. Hancock's coach arrived, and dressed, as always, in princely scarlet velvet, he made his way to the great pulpit, climbed the stairs, and waited for silence.

“He looked every inch an aristocrat,” according to one observer, “from his dress and powdered wig to his smart pumps of grained leather . . . sturdily built . . . dashing good looks . . . his dark eyes were penetrating,

his mouth was firm, his chin determined.”

15

Another called Hancock's facial expression “beautiful, manly, expressive.” His delivery could excite audiences to “the highest pitch of frenzy” or “sooth them into tears.”

16

On Massacre Day, 1774, Hancock did both as he delivered the most important speech of his lifeâin effect, seizing leadership of the American Revolution in Massachusetts. He began humbly, almost inaudibly:

Men, brethren, fathers and fellow-countrymen; The attentive gravity, the venerable appearance of this crowded audience; the dignity which I behold

in the countenances of so many in this great assembly; the solemnity of the occasion upon which we have met together . . . fill me with an awe hitherto unknown; and heighten the sense which I have ever had, of my unworthiness to fill this sacred desk. . . . I pray, that my sincere attachment to the interest of my country, and hearty detestation of every design formed against her liberties, may be admired as some form of apology for my appearance in this place.

Hancock raised his voice a bit:

I have always, from my earliest youth . . . considered it as the indispensable duty of every member of society . . . as a faithful subject of the state, to use his utmost endeavors . . . to oppose every traitorous plot which its enemies may devise for its destruction.

His voice grew stronger, reaching a crescendo:

I glory in publicly avowing my eternal enmity to tyranny! Is the present system, which the British administration have adopted for the government of the colonies, a righteous government, or is it tyranny?

“Tyranny!” the audience roared in response.

“Tell me, ye bloody butchers!” Hancock thundered. “Ye dark designing knaves, ye murderers, parricides! How dare you tread upon the earth, which drank the blood of the slaughtered innocents, shed by your wicked hands! How dare you breathe the air which wafted to the ear of heaven, the groans of those who fell a sacrifice to your accursed ambition!”

The crowd was his to command. Referring to the Tea Party, he charged that if Boston had not acted, “We soon should have found our trade in the hands of foreigners, and taxes imposed on every thing which we consumed.” He demanded “total disuse of tea in this country . . . to free ourselves from those unmannerly pillagers who impudently tell us that they are licensed by an act of the British parliament to thrust their dirty hands into the pockets of every American.” He called on all Patriots to arm themselves and prepare to “fight for your houses, lands, wives, children . . . your liberty

and your God” so that “those noxious vermin will be swept forever from the streets of Boston.”

He then sounded the clarion call for national rebellion and independence, urging Americans to organize militias and “be ready to take the field whenever danger calls” and appealing for “a general union among us . . . and our sister colonies.

“Much has been done by committees of correspondence . . . for uniting the inhabitants of the whole continent,” he declared, “but permit me here to suggest a general congress of deputies, from the several houses of assembly, on the continent, as the most effectual method of establishing such a union. . . .

I conjure you by all that is dear, by all that is honorable, by all that is sacred, not only that ye pray, but that you act; that, if necessary, ye fight, and even die, for the prosperity of our Jerusalem. . . . I thank God that America abounds in men who are superior to all temptation, whom nothing can divert from a steady pursuit of the interest of their country. . . . Their revered names, in all succeeding times, shall grace the annals of America. From them, let us, my friends, take example; from them, let us catch the divine enthusiasm and feel, each for himself, the God-like pleasure of . . . delivering the oppressed from the iron grasp of tyranny.

17

He finished with a passage from the Bible that left the immense crowd spellbound. As he descended the pulpit and shook hands with Sam Adams and other Patriot leaders, murmurs grew into applause, then erupted into cheers that swelled into a sustained roar as he made his way back to his coach to return to Hancock House. Old “Bishop” Hancock could not have stirred a congregation more than his grandson had just done. He had captured the hearts and minds of Boston's Patriot movement and become the undeniable leader of Massachusetts. John Adams called the oration “An elegant, a pathetic [in the sense of moving] and a spirited performance. A vast crowd, rainy eyes, etc. The composition, the pronunciation, the actionâall exceeded the expectations of everybody. They exceeded even mine, which were very considerable. Many of the sentiments . . . came from him with a singular dignity and grace.”

18

After a month of debate and deliberations, during which the East India Company tried in vain to recoup its losses from its insurers, the British government agreed on a sweeping new policy “to secure the dependence of the colonies on the Mother Country.” The new policy would punish not only the instigators of and participants in the Tea Party but the entire town of Boston for tolerating an atmosphere of indulgence that fostered the Tea Party. Declaring the Tea Party an act of high treason, the government equated it with “the levying of war against His Majesty” and “an attempt, concerted with much deliberation and made with open force . . . to obstruct the execution of an Act of Parliament.”

19

To punish the town, the British government ordered Boston's port closed to all ships beginning on June 15, until the city repaid the East India Company for its lossesâthe first of several “Coercive Acts” to force Boston to submit unconditionally to Parliament's rule.