American Tempest (23 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

Enough of the mob went home to restore a semblance of peace, and Hutchinson decided to implement his pledge immediately. The sheriff brought in Captain Preston at 2

A.M

. Although he insisted he had never given the order to fire, witnesses claimed he did, and a justice sent Preston to prison at 3

A.M

. The next morning, more than three thousand people gathered at Town House as the eight soldiers under Preston's command surrendered, were indicted for murder and imprisoned to await trial.

For a while, Boston awaited an even greater massacre. Merchants tried as best they could to protect their shops from looters. Appalled by the violence, Hancock remained cloistered in his mansion on Beacon Hill. Messengers from townâhis clerks, various followers, and othersâbounded up and down Beacon Street with breathless reports of the goings-on below. He was trapped in a war of madmenâeach set on destroying the other. He realized his own survival might depend on his taking personal control of the Patriots, unseating Sam Adams and the fanatics who controlled the mobs, and restoring calm to the streets of Boston. Regardless of the outcome of the conflict with Britain, reason would have to prevail. Hancock, like other moderate Boston merchantsâLoyalist and Patriot alikeânow sought peace in the streets and a return to normal life. Unfortunately, the radical merchants had encouraged their waterfront workers to march with the mob and allowed a hitherto docile, obedient underclass to experience independence, individual liberties, and the orgiastic satisfaction of successfully defying authority. In effect, the merchants had set loose beasts unable to distinguish between liberty and licenseâand would never be able to encage them again.

“Endeavors had been systematically pursued for months by certain busy characters,” John Adams noted, “to excite quarrels, encounters, and combats . . . in the night between the inhabitants of the lower class and the soldiers . . . to enkindle a mortal hatred between them. I suspected this was the explosion which had been intentionally wrought up by designing men who knew what they were aiming at better than the instruments employed.”

22

The court postponed the trial of Captain Preston and his troops until autumn to allow a return to calm and improve the chances of finding an impartial jury. Adams, Cushing, Hancock, and another assemblyman met with Hutchinson, Oliver, and British military commander Colonel Dalrymple at Town House to try to end the violence. With House Speaker Cushing acting as moderator, Hancock warned Oliver that “there were upwards of 4,000 men ready to take arms . . . and many of them of the first property, character and distinction in the province.”

23

Ten thousand more, he said, stood poised, muskets in hand, on the outskirts of Boston, their eyes fixed on Beacon Hill for the signal to march into Boston if British troops did not withdraw from the city.

Hancock was bluffing, of course, and both Dalrymple and Hutchinson knew he was bluffing, but all agreed that the violence had gone on too long and reached unnecessarily tragic proportions. Dalrymple agreed to withdraw his troops, and a few days later the Redcoats retreated to Castle William. A few weeks later Dalrymple eased tensions further, sending one of the two regiments at Castle William to New Jersey, thus cutting his troop strength in half.

Sam Adams, of course, could not reveal his role in provoking the Boston Massacre without incurring merchant outrageânot to mention charges of treason from the governor. Fearful of losing control, he rallied the Sons of Liberty, elevated the dead hooligans to near sainthood, and staged a grandiose procession with more than ten thousand mourners to carry them to their graves. Adams encouraged James Bowdoin, a friend from Harvard days, to write (anonymously) an inflammatory pamphlet. Entitled

A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre of Boston

, it called the shootings part of a conspiracy between the British army and customs commissioners to silence their critics. Although born to mercantile wealth,

Bowdoin was a radical who seldom let facts stand in the way of his conclusions. He sent his pamphlet to newspapers across the colonies and in Britain, where it received widespread circulation. The

Boston Gazette

of March 12 displayed Bowdoin's words edged in black mourning, charging that British soldiers had provoked the massacre by “parading the streets with drawn cutlasses and bayonets, abusing and wounding numbers of the

inhabitants.”

24

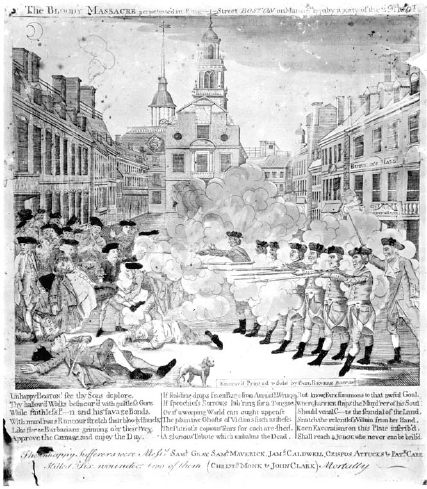

The issue included a provocative and grossly inaccurate drawing by Henry Pelham, the half-brother of portrait artist John Singleton Copley. Entitled “Fruits of Arbitrary Power, or The Bloody Massacre in King Street,” Pelham's drawing showed soldiers slaughtering helpless townsmen. Paul Revere made an engraving and sold prints of it, without permission or attribution.

25

In the days after the massacre, Sam Adams, Cushing, and Josiah Quincy, a lawyer who was the youngest son of Colonel Josiah Quincy of Braintree, wrote influential friends in London, including former Massachusetts Governor Pownall, “acquainting them with the circumstances and facts relative to the late horrid massacre and asking the continuance of their good services in behalf of this town and province.” The letter was designed “to prevent any ill impressions from being made upon the minds of his Majesty's ministers and others of the Town of Boston.”

26

Although Governor Hutchinson tried to restore calm by appealing to the General Court for help, Sam Adams and his followers would have none of it. They packed meetings with three and four thousand people to shout, hoot, cheer, sing, and do whatever else they could to disrupt proceedings. On March 15, Hutchinson followed the example of his predecessor Governor Bernard and ordered the General Court to meet in mob-free Cambridge across the water from Boston. The Court met there intermittently over the next six months, in an increasingly frustrating debate over whether the governor had the constitutional right to tell the House where to meet. In a surprise split with Samuel Adams, Hancock supported the governor. He sensed a growing alienation of rural representatives toward Adams and the Boston radicals for forcing delegates from across the state to travel into the dirty streets of Boston every time the Assembly convened. They welcomed the opportunity to meet in Cambridge, and Hancock joined them. After weeks of inaction, however, the governor finally ordered the Court adjourned until the following year.

Despite Sam Adams's efforts to rekindle the embers of violence, calmer voices began to prevail. Members of the Suffolk County Bar Association took the lead by organizing a force of three hundred lawyers, merchants, and other moderate townsmen to stand armed watch and patrol the town

to prevent further mob violence. Equipped with a musket, bayonet, broadsword, and cartridge box, the short, round, thirty-five-year-old attorney John Adams volunteered for and took his regular turn on sentry duty outside Town House. Recalling the Boston Massacre, he later concluded, “On that night the foundation of American independence was laid.”

27

“Let Every Man

Do What Is Right!”

N

ews of the repeal of the Townshend Acts cheered Boston's rational citizens and calmed the irrationalâexcept for the redoubtable James Otis, who continued acting so irrationally his family confined him to his home. At the end of May, he erupted in uncontrollable rage and began firing guns from his window over the heads of a large, frightened crowd. Friends subdued him and moved him to a safe haven in the country.

As with Stamp Act repeal, the official announcement of Townshend Acts repeal arrived on one of Hancock's shipsâagain confusing the Town Meeting as to whether Hancock had been a facilitator or simply a messenger. He did nothing to discourage their cheers, however, and, indeed, displayed numerous letters he had sent to men of influence in England that may or may not have affected repeal. Boston's eligible voters cast a resounding 511 of the possible 513 votes for Hancock in the May elections for the Massachusetts House of Representatives.

With the end of the Townshend Acts, trade between England and the colonies returned to normal. Renewed prosperity created jobs for the unemployed and weakened popular support for Sam Adams and the Sons of Liberty. The city also lost its appetite for vengeance against the

British soldiers who had languished in prison since the Boston Massacre. Moreover, two outstanding Patriot lawyersâJohn Adams and Josiah Quincyâhad agreed to represent the soldiers. Sam Adams tried to renew public hysteria, but to his dismay, the court allowed his cousin John to select a jury of men from outside Boston. None had ever lived under Redcoat occupation or harbored any animosities toward British troops. Several even had business ties to the British army, and five jurors later became Loyalist exiles. Using their challenges expertly, Adams and Quincy prevented the seating of even a single Son of Liberty or Bostonian on the jury. The first trial,

Rex v. Preston,

began on October 24, with Robert Treat Paine appointed prosecutor, with no option to refuse. Although a brilliant lawyer who, like all his colleagues and Boston friends, had graduated from Boston Latin and Harvard, he inherited a case that was laughably weak.

The first prosecution “witness” admitted he had not been on King Street the night of the tragedy. Other prosecution witnesses agreed that the crowd, not Preston, had shouted, “Fire!” John Adams and young Quincy quickly dismantled the prosecution's case, presenting thirty-eight witnesses to testify that civilians had plotted to attack the soldiers. In addition, they had the deathbed confession of Patrick Carr that the townspeople had been the aggressors and that the soldiers had not fired until attacked by “a motley rabble of saucy boys, Negroes and mulattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tars.”

1

At the end of the six-day trial, Chief Justice Peter Oliver presented the case to the jury and all but assured victory for the defense: “I feel myself deeply affected that this affair turns out so much to the disgrace of every person concerned against him [Preston], and so much to the town in general.”

2

The jury immediately acquitted Preston, but with Sam Adams's ruffians still calling for Preston's neck, the officer sought refuge at Castle William and returned to England, where the crown awarded him a handsome life pension of £200 a yearâtwice the average annual income of a skilled craftsman. Dr. Charles Chauncy, the longtime head of Boston's First Congregational Church and a leading member of Adams's “Black Regiment,” declared that if he had been a member of the jury, “I would bring him in guilty, evidence or no evidence.”

3

The trial of the eight soldiers began a month later on November 17, and on December 5, the jury acquitted six of them and found two guilty of manslaughter,

with mitigating circumstances. They were punished in the courtroom by being branded on their thumbs and released. On December 12, the jury, without leaving their seats to deliberate privately, dismissed charges that four customs officials had fired on the mob from the Customs House windows. Adams and Quincy proved that the boy who had been the star Patriot witness was a perjurer, coached and bribed by “divers high Whigs.”

4

With his power to control events in Boston slipping away, Sam Adams tried to incite resentment against the court and its verdicts in a series of anonymous articles in the

Boston Gazette

signed “Vindix.”

5

Although he portrayed the massacre as a slaughter of innocents by evil tyrants and their bloodthirsty mercenaries, his articles had little effect. The testimony at the soldiers' trials had unmasked Sam Adams as a sinister, power-hungry plotter willing to sacrifice innocent lives and destroy the city, if necessary, to further his designs. As the trial progressed, Adams's carefully constructed coalition of street toughs, laborers, artisans, merchants, lawyers, and Harvard intellectuals fell apart. The mob violence that Adams had generated the night of the massacre had turned even those merchants who opposed British rule against Adams and the radicals. Given a choice of tyranny by street toughs or tyranny by tariffs, all preferred the latter. The British not only maintained peace, their merchants paid in sterling. With all its faults, royal government, at least, represented stability. Governor Hutchinson reported to Lord Hillsborough that Massachusetts was displaying more “general appearance of contentment” than at any time since passage of the Stamp Act and that he hoped to build a Loyalist party as a political sanctuary for merchants and farmers.

6