American Tempest (12 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

As merchant protests against the Stamp Act grew in intensity, Otis and Adams stepped into the picture, citing the Magna Carta again to argue against taxation without representation. Grenville tried to strike back, reiterating that the vast majority of British taxpayers went unrepresented in Parliament and that representation could actually work to the disadvantage of American taxpayers. For one thing, members of Parliament were unpaid and any parliamentarians from America would incur inordinately

high costs of transportation and living expenses that would add to the burden of American taxpayers. In addition, the number of colonial representatives in Parliament would be too small to exert any legislative influence or quash demands of the majority of British taxpayers that colonists pay their fair share of taxes.

American printers and publishers refused to publish his or any other arguments in favor of the Stamp Act, however, because of its particularly harsh effects on their industry. “The Stamp Act . . . will affect the printers more than anybody,” grumbled Benjamin Franklin, Philadelphia's printer and copublisher of the

Pennsylvania Gazette

. With a stamp required for every newspaper they printed and sold, Franklin and the editors of almost all twenty-six newspapers in America rallied behind merchant protests and gladly featured Otis's diatribes.

The Stamp Act infuriated many lawyers as well, enticing the otherwise retiring thirty-year-old country lawyer John Adams into politics for the first time in his young career. He went before the Braintree Board of Selectmen to demand that they instruct the Massachusetts agent in Parliament to seek repeal of the act. “We can no longer forbear complaining,” Adams barked, “that many of the measures of the late acts of Parliament have a tendency . . . to divest us of our most essential rights and liberties.” Calling the Stamp Act too burdensome, he predicted that it would “drain the country of its cash, strip multitudes of all their property, and reduce them to absolute beggary.

We further apprehend this tax to be unconstitutional.

*

We have always understood it to be a grand and fundamental principle of the constitution that no freeman should be subject to any tax to which he has not

given his own consent, in person or by proxy . . . that no freeman can be separated from his property but by his own act or fault.

Adams went on to demand “explicit assertion and vindication of our rights and liberties . . . that the world may know . . . that we can never be slaves.”

6

With all-but-universal opposition to the Stamp Act among merchants, newspapers, and lawyers, the outrage spread across the nation. In Virginia, Assemblyman Patrick Henry, a lawyer himself, resolved that

the General Assembly of this colony have the only and sole exclusive right and power to lay taxes . . . upon the inhabitants of this colony, and that every attempt to vest such power in any person or persons . . . other than the General Assembly . . . has a manifest tendency to destroy British and American freedom.

7

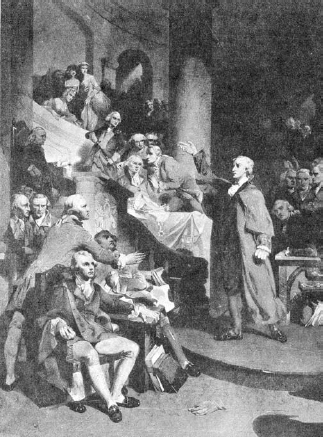

Although the Speaker of the House interrupted Henry with an angry cry of “Treason, sir!,” Henry responded by warning, “Caesar had his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell, and George the Third may profit by their example! If

this

be treason, make the most of it!”

8

The House erupted in a cacophony of angry shouts and jubilant cheers. “Violent debates ensued,” Henry recalled. “Many threats were uttered, and much abuse cast on me. After a long and warm contest, the resolutions passed by a very small majority, perhaps of one or two only.”

9

After hearing Henry's condemnation of the Stamp Act, both Richard Henry Lee and George Washington, the owners of two of Virginia's largest plantations, abandoned the ranks of pro-British planters in the Assembly and voted with Henry. Henry, in fact, had prepared seven resolutions, but presented only five before deciding he had gone far enough. His last two called for outright disobedience of the Stamp Act and rebellion against the motherland.

Outraged by what he considered nothing less than a coup d'état, Virginia's conservative Speaker of the House acted swiftly to reassert his authority, engineering a reassessment and rejection of Henry's resolutionsâbut his action came too late. Henry had already given the editor of the

Virginia

Gazette

all seven resolutions to copy, and under a news-sharing agreement among newspaper printers in most of the colonies, the

Gazette

editor had already sent them across America. “The alarm spread . . . with astonishing quickness,” Henry chuckled. “The great point of resistance to British taxation was universally established in the colonies.”

10

A week later, Henry's resolutions appeared in the Annapolis, Maryland, newspaper; by mid-June they were in the Philadelphia, New York,

and Boston papers, and by early August in the Scottish and British press. Newspaper publishers in Britain were at one with American publishers in despising the Stamp Act, which required them to put a stamp on every copy they sold in Britain. With each publication of Henry's resolutions, collective exaggerations, misinterpretations, and copying errors transformed them into nothing less than a call to revolution. His sixth resolution, according to the

Maryland Gazette

, declared that Virginians were “not bound to yield obedience to any law or ordinance whatsoever, designed to impose taxation upon them, other than the laws or ordinances of the General Assembly,” and his seventh resolution called anyone who supported Parliament's efforts to tax Virginians “AN ENEMY TO THIS HIS MAJESTY'S COLONY.”

11

The

Boston Gazette

, which was published by two vitriolic antiroyalists, Benjamin Edes and John Gill, also printed all seven of what they called Henry's original resolutions and claimed falsely that Virginia had adopted them all intact. Described as “foul-mouthed trumpeters of sedition” by the rival, pro-British

Boston Chronicle

, Edes and Gill had met as apprentice printers and formed a partnership printing books, broadsides, and pamphlets that featured only sermons at first but gradually included better-selling polemics by gifted provocateurs such as Samuel Adams.

Publication of Henry's resolutions fired up colonist antipathy toward British government intrusion in their affairs and Parliament's efforts to tax them. Stamp Act opponents rallied in every city, forming secret societies called Sons of Liberty, which would soon evolve into the Tea Party movement.

“The flame is spread through all the continent,” Virginia's royal governor Francis Fauquier warned his foreign minister in London, “and one colony supports another in their disobedience to superior powers.”

12

Governor Sir Francis Bernard of Massachusetts agreed, warning the ministry that Henry's resolutions had sounded “an alarm bell to the disaffected.”

13

After reading Henry's resolutions in the

Boston Gazette

, the Massachusetts assembly called on all colonies to send delegates to an intercolonial congress to be held in New York City in October, one month before the Stamp Act was to take effect.

On August 8, the British government published the names of colonial distributors who would sell stamps. The distributor for Massachusetts was Andrew Oliver, the wealthy Boston merchant who was also Chief Justice Hutchinson's brother-in-law. The appointment seemed proof positive of James Otis's charges two years earlier that wealthy merchants and the royal government were conspiring to forge “chains and shackles for the country” and “grind the faces of the poor without remorse, eat the bread of oppression without fear, and wax fat upon the spoils of the people.”

14

Andrew Oliver ignored Otis's charges, pointing out that no less a man than Benjamin Franklin had applied to be a stamp distributor. Far from grinding the faces of the poor, Oliver had been one of Boston's most generous philanthropists, using his own money to help pave Boston's streets and to feed and house the poor. A leader in the effort to send Congregationalist missionaries among the Indians, he was a major supporter of Eleazar Wheelock's missionary school for Indians (later Dartmouth College).

Publication of Henry's resolutions, however, aroused too many pent-up emotions. As one, Bostonians seemed to snap. Debts had piled high, there was no work, shops had closedâwith nothing left for rent or food, many tramped off into the wilderness, hoping that something would turn up. Early in the morning on August 14, an effigy of Andrew Oliver dangled from the limb of a huge oak tree on High Street near Hanover Square, drawing the attention of the curious at first. Planted three years before the beheading of King Charles I in 1649, the oak had quickly acquired an appropriate titleâthe Liberty Tree.

As angry faces began crowding around it, Governor Bernard ordered deputies to disperse them, but the deputies refused, saying any effort would put them in “imminent danger of their lives.” Sam Adams appeared with a group of followers that included printer Edes of the radical

Boston Gazette

, and distillers John Avery and Thomas Chase, who wielded an inordinate amount of power in local government by offering political leaders a room in the distillery as a clubhouse and assuring them a steady flow of free “punch, wine, pipes, and tobacco, biscuit and cheese.”

15

After Adams and the others had spoken, the mob dispersed and the men returned to work, but at Adams's invitation, they pledged to return

later in the day. The second, bigger rally drew a rougher crowd of waterfront workers and laborers, who set to drinking free rum offered by the Chase and Speakman distillery. They soon raged out of control, tore down Oliver's effigy, and carried it to the windows of the governor's office at the Town House, or state capitol, where they chanted defiantly, “Liberty, Property, and No Stamps.”

Growing in number, they moved toward a half-finished brick building near the waterfront where Oliver planned to let out shops. Believing it would house the stamp office, the mob tore it down, brick by brick, ripping off and burning the wooden sign that bore Oliver's name. With nothing left to destroy, they rushed off to Oliver's beautiful estateâthe mangled effigy still in tow. Once in front of the Oliver mansion, they beheaded and burned the straw dummy with great ceremony, then set to stoning the windows and uprooting fruit trees and flowers in the beautiful garden. Unsatisfied, they cried for a hangman's rope, smashed the windows and broke down the mansion's doors. When they realized Oliver had fled with his family, they destroyed the magnificent furniture, art, mirrors, china, crystal, and everything else they could lay hands on.

16

Chief Justice Hutchinson and the county sheriff raced to the scene and tried to reason with the mob, but its leaders responded with volleys of epithets and stonesâdriving the two away. Governor Bernard ordered the colonel of the militia to summon his regiment, but the drummers who normally sounded the alarm were part of the mob, as were many of the employees of the Hutchinson, Hancock, and Oliver merchant-banking houses.

“Everyone agrees,” the governor wrote to the Board of Trade in London, “that this riot had exceeded all others known here, both in the vehemence of action and mischievousness of intention.”

17

The teapots of Boston had come to a boil and threatened to explode into a tempest.

Â

______________

*

Britain did not have (nor does it now have) a constitution in the form of a single, American-style documentâonly a “customary” or conceptual constitution made up of documents (letters, opinions, declarations, decisions from the bench, etc.), written statutes, and common law, often based on old, established, and widely practiced customs. Under the British “constitution,” Parliament, as primary law giver and center of power in eighteenth-century England, could do anything it wanted, thus refuting arguments that the Stamp Act was unconstitutional and leaving opponents of such acts to choose between either obeying or declaring independence.