American Tempest (10 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

Flockwork from England

L

ike Hutchinson, Oliver, Clarke, and other scions of Boston's mercantile aristocrats, Hancock had never questioned the rule of God, King, and Country. The third of his line to carry his Christian name, his forebears had arrived from England in 1634, only fourteen years after the

Mayflower

. The first John Hancock graduated from Harvard in 1685 and stepped into the pulpit of the North Precinct Congregational Church of Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1698. After fifteen years, he led a tax revolt in which the North Precinct declared independence and adopted a new nameâLexington. Quickly dubbed “the Bishop of Lexington,” he brooked no opposition to his iron-fisted rule and became the first Hancock to join the ruling class of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. His power, like that of other Congregationalist ministers, stemmed from the determination of early Puritan settlers to found a “Bible Commonwealth” in Massachusetts. They limited free speech and political privileges and imposed in New England the same religious discrimination that Anglicans had imposed on them in old England. They limited voting rights to propertied male members of their church and converted town after town into theocracies, where ministers ruled the spiritual world and deacons and elders the material world.

The first of the bishop's five children also bore the name John Hancock and entered the ministry. And from the moment

his

sonâJohn

Hancock IIIâwas born in 1737, his family had little doubt that he would follow the first and second John Hancocks into the pulpit. In 1744, however, John Hancock III's father became ill and died, and another Hancock appeared at the manse in Lexington in an English-built, gilt-edged coach and four, attended by four liveried servants. A silver and ivory coat of arms emblazoned its doors. Beneath it, heraldic gold script proclaimed,

nul plaisir sans peine

(no pleasure without pain). Thomas Hancock, the bishop's second son, who had left as a fourteen-year-old indentured apprentice, had returned home after twenty-seven years as one of America's richest, most powerful merchants, the owner of Boston's world-renowned House of Hancock.

Like Hutchinson, Oliver, and Boston's other powerful merchants, Hancock's enterprise included retailing, wholesaling, importing, exporting, warehousing, ship and wharf ownership, commercial banking, investment banking, and real estate investments. What made his and the other merchant banks unique was that they had achieved success in what was then the richest city in the New World: Boston. Although no one had a firm idea of all the things that the House of Hancock and the other merchant-banking firms traded, everyone knew that whatever in the world one might want, one could find it at Thomas Hancock's, and if he didn't have it, he could get it for a price. Every bit as overwhelming as his father the bishop, Thomas Hancock could buy anything he wanted, and what he wanted more than anything else in the world when he strode into his dead brother's house in the summer of 1744âand what he intended to buy at any priceâwas a son and heir to the House of Hancock. Married but unable to have children of his own, Thomas Hancock had spent twenty-seven years building his commercial empire, and he was not about to let it fall into the hands of strangers after his death. His older brother's death provided the first opportunity to adopt an acceptable child. Thomas pledged to provide lifelong security in the most generous fashion for his brother's widow Mary and all three childrenâif Mary would allow him to raise the older boy, John, as his own in Boston. He promised to give the boy the finest schooling, culminating at Harvard, where he would follow in his father's and grandfather's educational footsteps. All but penniless, Mary Hancock had little choice but to yield to

the forceful merchant king and watch as her little boy, the third and soon to be the greatest John Hancock, left the manse in Lexington and waved goodbye from his uncle's stately carriage.

Although Thomas Hancock lacked the Harvard credentials of Boston's other merchant-aristocrats, he more than matched them in his bearing and demeanorâfrom his immaculate, carefully powdered wig to his silver shoe buckles. Embroidered ruffled shirt cuffs flared from the ends of his jacket sleeves and embraced his soft, puffy hands. The rest of his costumeâthe magnificent knee-length velvet coat and the shirt frills that peeked discreetly from the front of his jacketâshowed the care he took to compensate for his academic deficiencies with well-displayed evidence of wealth, power, and high standing. A gold chain held a magnificently fashioned watch in his waistcoat pocket.

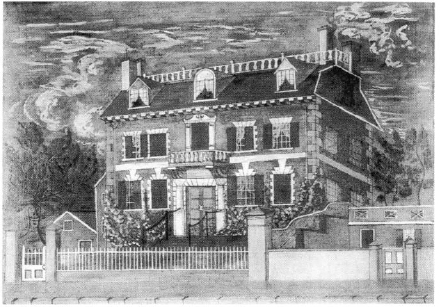

Hancock lived on the edge of the Common at the peak of Beacon Hill in one of Boston's grandest homesâa three-story palace that differed only in its exterior architecture from the homes of Boston's other great mansions. Hancock had acquired the land for next to nothing when it was but a pasture, and he kept on buying property until he owned the entire crest of Beacon Hill and half the town below, including the massive Clarke's Wharf, Boston's second-largest wharf.

“He had raised a great estate with such rapidity,” wrote Thomas Hutch inson, “that it was commonly believed that he had purchased a valuable diamond for a small sum and sold it at its full price.”

1

Built of square-cut granite blocks and trimmed at each corner with brownstone quoins, Hancock House looked out on the Common through four large windows that framed a central entrance. A large balcony above the door commanded a breathtaking, panoramic view that swept across the entire Common, the city, harbor, and sea beyond as well as the surrounding countryside. In all, the house had fifty-three windows, including those in the dormers, lighted by 480 squares of the best crown glass from London.

Outside, a two-acre landscaped green bore a variety of shade trees and elegant gardens. At the far end, a small orchard included mulberry, peach, and apricot trees from Spain. A gardening enthusiast, Hancock ordered many trees and plants from English nurseries and unwittingly enriched

the entire New England landscape with species of trees, shrubs, and flowers that were new to North America. All originated from wind-blown seeds from Thomas Hancock's gardens on Beacon Hill.

He told one horticulturist:

to procure for me two or three dozen yew trees, some hollys and jessamine vines; and if you have any particular curious things . . . [that] will beautify a flower garden, send a sample. . . . Pray send me a catalogue of that fruit you have that are dwarf trees and espaliers. . . . My gardens all lie on the south side of a hill, with the most beautiful assent to the top; and it's allowed on all hands that the kingdom of England don't afford so fine a prospect as I have both of land and water. Neither do I intend to spare any cost or pains in making my gardens beautiful or profitable.

2

Hancock's gardens were the most beautiful and most envied in Boston.

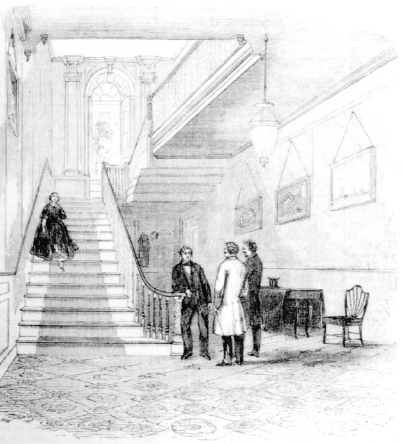

Inside his house, a wide, paneled, central entrance hall reached through to a set of rear doors that looked onto the formal gardens. Delicately carved, spiral balusters bounded a broad staircase that rose along the left wall of the main hall. A ten-foot-tall “chiming clock,” topped with sculpted figures, “gilt with burnished gold,” stood against the opposite wall. Oil portraits of important men in uniform or formal clothes stared out from large gilded frames on the walls in the rooms off the hall, casting silent judgments on all who entered. The great parlor, or drawing room, lay off the hall to the right as one entered the house, and the family sitting room sat opposite. Mahogany furniture filled the parlor, upholstered in luxurious damask that matched the drapes. Imported green-scarlet “flockwork” from Englandâa “very rich and beautiful fine cloth” wall covering ornamented with tufts of wool and cottonâcovered the walls. Elegant brass candlesticks sparkled with reflected light from the marble hearthâone of three downstairs. Servants kept fires burning in every room during the cold Boston winters. Across the hall, English wallpaper in the family room displayed brightly colored “birds, peacocks, macaws, squirrels, fruit and flowers” that Hancock described as “better than paintings done in oil.”

3

Beyond the family room was the dining room and kitchen, which included “a jack of three guineas price, with a wheel-fly and spitt-chain to it.” One of the smaller rooms behind housed Hancock's huge china collection, and the other rooms served as lodgings for servants and slaves. Hancock stocked his cellar with Madeira wines that he bought “without regard to price provided the quality answers to it.” He also bought a docile slave named Cambridge for £160 to help serve his and his wife Lydia's many guests from “6 quart decanters” and “2 dozen handsome, new fashioned wine glasses” made of the finest rock crystal from London.

4

Upstairs, above the parlor, sat the huge guest bedroom, with furnishings and matching draperies in yellow damask. Years later, its canopied four-poster bed would sleep, among others, Sir William Howe, commanding general of the British Army in America during Washington's siege of Boston in the winter of 1775â76. Opposite the guest room stretched the master bedroom, done in crimson. Two other smaller bedrooms lay on the second floor, with storage and servants' quarters scattered above, beneath the roof. “We live pretty comfortable here on Beacon Hill,” Thomas Hancock purred modestly.

5

Within hours of entering his new home on the hill, little John Hancock began a year of intensive training with a private tutor, who transformed the country boy into a city sophisticate, with impeccable manners, speech, and behaviorâa model of mid-eighteenth-century Anglo-Boston society. His doting aunt Lydia, Thomas Hancock's wife, groomed and dressed him in velvet breeches with a satin shirt richly embroidered with lace ruffles at the front and cuffs. His shoes bore the same sparkling silver buckles as those of his uncle. Thomas Hancock was immensely proud of his adopted son's

good looks, and as quickly as the boy's bearing and manners permitted, he made a ceremony of introducing him to the scores of military and government leaders, including the royal governor, who constantly came to pay court to the great merchant and dine at his wife's fine table.

In July 1745 John Hancock was ready to enroll in the prestigious Boston Public Latin School on School Street at the bottom of Beacon Hill behind the Anglican King's Chapel, where he joined the sons of every other merchant-banker in Boston. A two-story wooden building with a neat peaked roof and belfry, Boston Public Latin was the academic gateway to Harvard College and leadership in church, business, and government. It was no place for a rebel. Thirty years earlier, ten-year-old Benjamin Franklin had bridled under the harsh discipline and quit Boston Latin after only two years there.

Headed by Tory martinet John Lovell, the school put John through five years of torturous studies, stretching from seven in the morning to five in the afternoon, four days a week, and from seven to noon on Saturdays. There was no school on Thursdays, Sundays, and fast days, nor on Saturday afternoons. School ran the year around, with only a week's vacation at Thanksgiving and at Christmas and three weeks off in August. In the end, Hancock and other survivors of Lovell's brutal pedagogy learned to venerate the king; to read, write, and speak fluent Latin and Greek; to read and cite the Old and New Testament in both languages; and to read and cite the works of Julius Caesar, Cicero, Virgil, Xenophon, and Homer. He entered Harvard in the autumn of 1750 at the age of thirteen and a halfâthe second youngest in his class of twenty, but ranked fifth because of his uncle's wealth, power, and social standing and John's own heritage as the son and grandson of Harvard alumni. The prospect of a generous legacy from his wealthy uncle did not hurt his ranking. Four years later, he graduated with his degree and the right to be called “Sir Hancock” whenever he set foot on the Harvard campus. No sooner had he graduated than his uncle put him to work in the House of Hancock, learning every aspect of merchant-banking in preparation for his ascendancy to full partnership with his uncle and eventual inheritance of their vast enterprise. Young John rode to work each day with his uncle in the splendid family carriage, dined at the Merchants Club with the city's other great business magnates,

joined the Freemasons, and became close friends with the heirs to other great merchant fortunesâThomas Hutchinson, Jr., Andrew and Peter Oliver, Thomas Cushing, Jr., and James Bowdoin, Jr. All embraced wealth and its accouterments with equal passion, and they dressed and dined accordingly. All were Men of Harvard, and in unison, they sang the praises of the king and country that had blessed them with abundance.