American Tempest (22 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

As the mob retreated and dissolved, other Loyalist merchants took heart from Hutchinson's stand, and Adams and his radicals responded in kind, deeming four such merchants “obstinate and inveterate enemies to their country and subverters of the rights and liberties of this continent.” A second vote condemned six other recalcitrant merchants “to be driven to that obscurity from which they originated and to the hole of the pit from whence they were digged [sic].” And a third vote demanded an end to tea consumption “under any pretense whatever.”

5

But an end to tea consumption rubbed many ladies the wrong way.

“The people take a great deal of tea in the morning,” French Baron Cromot du Bourg reported in his diary,

Journal de mon séjour en Amérique

. “They drink tea with dinner at two in the afternoon,” he said, and “about five o'clock they take more tea, some wine, Madeira, and punch.”

6

Indeed, tea had addicted most American women in the upper social and economic classes, along with those with aspirations of attaining or pretensions to that status. Foreign visitors to America at the time found that tea had become a standard breakfast drink of the wealthy in both New York and Philadelphia. Naturalist Peter Kalm noted that for upper social classes in Albany, New York, “their breakfast is tea, commonly without milk. . . . With the tea was eaten bread and butter or buttered bread toasted over the coals so that the butter penetrated the whole slice of bread. In the afternoon about three o'clock tea was drunk again in the same fashion, except this time the bread and butter was not served with it.”

7

And in Boston, “The ladies here visit, drink tea, and indulge in every little piece of gentility to the height of the mode and neglect the affairs of their families with as good grace as the finest ladies in London.”

8

An end to tea consumption, therefore, represented a considerable sacrifice for many an American ladyâespecially for those who tried substituting the vile “labradore” tea derived from swamp bushes. As one Virginian wrote plaintively to her friend in England, “I have given up the article of tea, but some are not

quite so tractable. However, if we can convince the good souls on your side of the water of their error, we may hope to see happier times.”

9

Patriot newspapers supported the end of tea consumption with lyrical appeals: “Throw aside your Bohea and your Green Hyson Tea,” urged a self-styled poet in the

Boston Post-Boy

,

and all things with a new fashion duty;

Procure a good store of the choice Labradore,

For there'll soon be enough here to suit ye;

These do without fear, and to all you'll appear

Fair, charming, true, lovely, and clever;

Though the times remain darkish, young men may be sparkish,

And love you much stronger than ever.

10

With Hutchinson and Clarke standing tall against the radicals, Molyneux led a mob to the homes of the smaller, less-resilient recalcitrants, shattering the windows of one after another and forcing them to turn over their shipments of tea to the mob. On February 22, 1770, they marched to the shop of Ebenezer Richardson, and as he took refuge inside, a barrage of stones shattered the building's windows. An out-of-work seaman came to his aid, and as the mob broke down the door, Richardson appeared at the window above, a musket barrel poised and protruding. As the rain of rock persisted, he fired a blast of swanshotâsmall pellets that spread as they approached their target. The pellets wounded a nineteen-year-old and killed an eleven-year-old German boy, Christopher Seider. Seider's death inflamed Boston's street mobs. In effect, it proved to be the first death of what evolved into the American Revolution.

Sam Adams turned the Seider funeral into the largest ever held in Americaâan enormous mass mourning of a martyr that began at 5

P.M.

at the Liberty Tree, where Adams had affixed a board bearing the inscriptions

Thou shalt take no satisfaction for the life of a MURDERERâhe shall surely be put to death.

and

Though hand join in hand, the wicked shall not pass unpunish'd.

The procession stretched more than a half-mile, with more than four hundred carefully groomed, angelic schoolboys marching two by two, cloaked in white, leading the coffin. Six youths carried the coffin; two thousand mourners led by the boy's family and friends followed, with thirty chariots and chaises behind them.

“Mine eyes have never beheld such a funeral,” said John Adams. “This shows there are many more lives to spend if wanted in the service of their country. It shows too that the faction is not yet expiringâthat the ardor of people is not to be quelled by the slaughter of one child and the wounding of another.”

11

The radical

Boston Gazette

said Seider's death “crieth for vengeance. . . . Young as he was, he died in his country's cause.”

12

Relations between colonists and British troopsâalready viciousâreached a new low. The air filled with a constant staccato of catcalls and cries of “Lobster; hey lobster!” at red-coated British officers. Fights erupted on the waterfront between “lobsters” and “mohawks”âwith Sam Adams never far away, goading his street toughs to harass, insult, and provoke violence. General Gage recognized his error in ordering troops to Boston:

The people were as lawless and licentious after the troops arrived as they were before. The troops . . . were there contrary to the wishes of the Council, Assembly, magistrates, and people, and seemed only offered to abuse and ruin. And the soldiers were either to suffer ill usage and even assaults upon their persons till their lives were in danger, or by resisting and defending themselves, to run almost a certainty of suffering by the law.

13

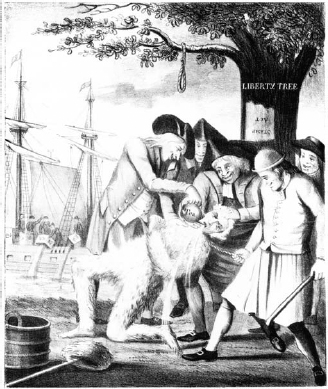

More than soldiers, customs commissioners remained the targets of the mob, with more than one of them overtaken, stripped, and doused with scalding tar, then feathered and carried about the town and subjected to unconscionable humiliations.

At the beginning of March, the king appointed Hutchinson governor, who, in turn, ceded his post as chief justice to his brother-in-law Peter Oliver. As two of Boston's great merchant-bankers, they had the support of Loyalist merchants and moderates in Boston's business community who had tired of the violence that political radicals generated. Most now longed for stability and peace in a tax-free climate that would allow them

to prosper. In elevating Americans to the chief posts in the executive and judiciary, the king hoped also to placate Boston's malcontents by giving them a sense that two of their own now controlled provincial affairs. The king went a step farther by appointing Hutchinson's brother-in-law, Peter Oliver's brother Andrew, lieutenant governor. In effect, three Americans, whose roots stretched to the first settlements in the New World, now held the three most powerful posts in Massachusetts, and Britons were nowhere to be seen in government.

Hutchinson and Oliver could not have assumed their new posts at a worse time, however. “I thought I could support myself well enough at

first,” Hutchinson wrote in dismay to former Governor Pownall in London, “but the spirit of anarchy which prevails in Boston is more than I am able to cope with.”

14

From the moment the Seider boy went to his rest, townsmen seldom let a moment pass without provoking fights with soldiers. On March 2, ropemaker Samuel Gray, one of Mackintosh's most brawl-hardened street toughs, approached a soldier who was seeking part-time work and offered the Redcoat a job cleaning the ropemaker's privy. As onlookers cawed with laughter, the soldier called to his comrades; together, they plunged into a brawl that flashed intermittently for the next three days and nights. Gangs of boys continually provoked conflict by pelting the Redcoats with snowballs, pieces of ice, whole oysters in their shells, stones, glass bottles, and other missiles.

On the evening of March 5, belligerent bands of laborers and boys roamed the streets, provoking fights with British soldiers wherever the opportunity presented itself. A wigmaker's apprentice, of all people, set off a ruckus on King Street, accusing a British officer of not paying his bill. As a small mob surrounded them, another ruckus erupted near the British barracks on Brattle Street, where a mob leader confronted a British officer, demanding, “Why don't you keep your soldiers in their barracks?” As the mob drew closer, a small boyâperhaps seven or eightâemerged screaming, his hands cupping his head, and asserting that the British officer had killed him. And at one end of Boylston's Alley, another mob had surrounded a contingent of junior officers, pelting them with snowballs while screaming accusations: “Cowards! Afraid to fight!” Meanwhile, a fourth mob of about two hundred surged into the market on Dock Square, brandishing wood bats, breaking into market stalls and crying, “Fire! Fire!”

“It is very odd to come to put out a fire,” Scotsman Archibald Wilson remarked, “with sticks and bludgeons.”

15

At 9

P.M.

, as if on signal, the town's bells began pealing, and a young barber's apprentice taunted a sentry at the Customs House on King Street. The sentry slapped the boy, sending him sprawling onto the street. He bounded up and went off screaming for help as the bells continued their mournful peals. A crowd of boys materialized and pelted the sentry with snowballs,

all the while shouting, “Kill him, Kill him. Knock him down.”

16

And the bells continued pealing.

A crowd of men joined the boys in taunting the Redcoats while men everywhere rushed out of their homes thinking a fire had broken out. Mobs surged through the streets in every direction. At Faneuil Hall a man variously described as tall and wearing a red cloak and white wig was haranguing a crowd of men into a frenzy, while another crowd gathered at the Redcoat barracks.

By this time, Captain Thomas Preston, the officer of the day, had heard of the sentry's predicament at the Customs House. He marched six privates and a corporal to the scene, bayonets fixed, intent on escorting the sentry into the Customs House, away from the mob's missiles and taunts. By the time he reached the sentry's post, small gangs swept in from all directions. The mob swelled and made it impossible for Preston to march away. Volleys of ice, oyster shells, and sticks rained on the troops. Ropemaker Samuel Gray, Crispus Attucks (a massive “mulatto fellow,” according to later testimony), ship's mate James Caldwell, and Patrick Carr, “a seasoned Irish rioter,” pushed their way to the front of the crowd with a group of sailors.

17

“The multitude was shouting and huzzaing, and threatening life; the bells were ringing, the mob whistling, screaming and rending Indian yells; the people from all quarters were throwing every species of rubbish they could pick up in the streets”âall the while, daring the soldiers to fire. As the missiles rained on the soldiers, some townsmen lunged at them with sticks held as swords, crying “bloody backs,” “lobsters,” and other epithets.

18

Attucks then hurled his club at one of the soldiers. It found its mark, the soldier fell, then staggered to his feet. The cry of “Damn you! Fire!” resounded across the scene, and he fired into the crowd. A second soldier fired a hole into Gray's skull, and before his body hit the ground, a volley of shots left four others dead. Attucks and Caldwell fell at the feet of the beleaguered soldiers. Eight others lay wounded, including Carr and a seventeen-year-old, both of whom later died of their wounds. The other six recovered.

19

Samuel Adams now had the massacre he had sought to incite a revolution against British rule. He sent messengers into the country to alert farmers to arm themselves but to await ignition of a bonfire on Beacon Hill as a signal to march on Boston.

In the terrifying moments after the shootings, Preston and his men returned to the main guard house and prepared for an assault by the mob, now rumored to have reached five thousand. The British regiment quartered at Town House, already seething from months of insults and assaults, moved toward King Street prepared to crush a rebellion. Governor Hutchinson knew that unless he took control immediately, “the whole town would be up in arms and the most bloody scene would follow that had ever been known in America.”

20

Hutchinson raced to Town House, and as the crowd gathered beneath the second-floor balcony, he called on them to return to their homes. “The law shall have its course,” he promised. “I will live and die by the law.”

21