American Tempest (13 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

A Diabolical Scene

A

fter the destruction of Andrew Oliver's beautiful home, Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson tried to make sense of what seemed an unimaginable spasm in an edenic land that had harbored and nurtured generations of their families for 150 years.

Americans were convinced in their own minds that they were very miserableâand those who think so are so. There is nothing so easy as to persuade people that they are badly governed. Take happy and comfortable people and talk to them with the art of the Evil One, and they can soon be made discontented with their government, their rulers, with everything around them, and even with themselves. This is one of the weaknesses of human nature of which factious orators make use of to serve their purposes.

1

Although Samuel Adams was a familiar figure in Boston's taverns and had certainly harangued the mob at the Liberty Tree, there is no evidence he personally took part in the Oliver attack. He took full advantage of the excitement it generated, however, to organize a Boston branch of the Sons of Liberty. Its membership, which would remain known only to him and the group's other leaders, would later gain national and international fame as Boston's Tea Party Patriots.

The next morning, an unidentified “group of gentlemen” approached Andrew Oliver, threatening to destroy what was left of his property and menacing him and his family unless he resigned as stamp distributor.

“He was carried to the Tree of Liberty by the mob,” his younger brother Peter Oliver recalled, “and there he was obliged on pain of death to take an oath and resign his office.”

2

Although Sam Adams said the night's events and those of the following day “ought to be forever remembered . . . [as] the happy day, on which liberty rose from a long slumber,”

3

merchant John Hancock was appalled at the mob attack on one of his friends. Thirty years older than Hancock, Oliver was also a Harvard graduate, son of a great merchant, grandson of a prominent surgeon and ruling elder of the Boston churchâthe third generation in a distinguished Massachusetts family whose roots reached back to 1632, twelve years after the landing at Plymouth. John Hancock knew that a large number of near-bankrupt smaller merchants and shopkeepers had been in the mob that attacked Oliver. Hancock suddenly felt isolated in an increasingly polarized city. As a wholesaler, he had strong ties to the small merchants and shopkeepers whom he supplied, but his wealth, his international merchant-banking enterprise, and his fleet of ships made him an intimate member of the plutocracy of large merchants like Hutchinson, Oliver, and others with deep loyalties to Mother England.

Thinking he could influence events in England and douse the embers of rebellion in America, Hancock again wrote to his London agent of the “general dissatisfaction here on account of the Stamp Act, which I pray may never be carried into execution. . . . It is a cruel hardship upon us and unless we are redressed we must be ruined. . . . Do exert yourselves for us and promote our interest. We are worth saving but unless speedily relieved we shall be past remedy.”

4

Hancock's warnings proved all too accurate. The epidemic of mob violence spread to Newport, where a mob plundered the homes of a wealthy lawyer and an eminent physician for defending the Stamp Act. Similar assaults ravaged homes in towns along the Hudson River Valley, in New York City, Philadelphia, Charleston . . . rioting erupted again in Boston on August 26, when rumors swept through the city that the “whole body of Boston merchants had been represented as smugglers” in depositions by

the royal governor seeking their arrest. Although Governor Bernard denied making any such charges, merchants “descended from the top to the bottom of the town” to Town House. A mob gathered, lit a bonfire, and began drinking and shouting “Liberty and Property”âwhich Governor Bernard described as “the usual notice of their intention to plunder and pull down a house.”

5

The mob eventually marched to the home of the marshal of the vice-admiralty court, who saved his home by leading them to a tavern and buying a barrel of punch. Now drunker than before, they staggered to the home of another court official, broke down the doors, and burned all court records before wrecking the house and its contents. A second mob smashed into the elegant new home of the comptroller of the customs, who had just arrived from England. After the mob had sacked the houseâand finished drinking all the wines in its cellarâEbenezer Mackintosh, a leatherworker/shoemaker and fire brigade commander, led both mobs to Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson's home.

Peter Oliver later charged Samuel Adams, James Otis, and other antiâ Stamp Act activists with hiring Mackintosh to do “their dirty jobs for them.” Oliver said Mackintosh

dressed genteely . . . to convince the public of that power with which he was invested. . . . He paraded the town with a mob of 2,000 men in two files, and past by the Stadthouse when the General Assembly was sitting, to display his power. If a whisper was heard among his followers, holding up his finger hushed it in a moment, and when he had fully displayed his authority, he marched his men to the first rendezvous and ordered them to retire peaceably . . . and was punctually obeyed.

6

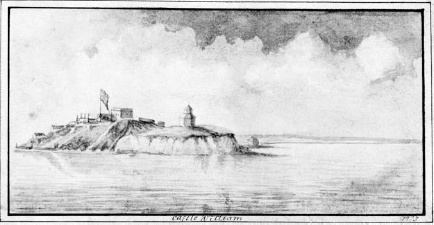

Lieutenant Governor Hutchinson's home had stood as one of North America's architectural jewels: a palatial Inigo Jonesâstyle residence with Ionic pilasters framing its facades, crowned by a delicate cupola on its roof. Warned of the mob's approach, Hutchinson ordered his family to leave while he and Governor Bernard confronted the mob. His daughter refused to leave without him, however, and they fled with Bernard to the protection of British troops on Castle William, the island fortress in Boston Harbor (see

map 2

,

page 82

). The mob broke down the massive doors and,

room by room, destroyed everything they could lay their hands on, including Hutchinson's legendary collection of manuscriptsâmany of them significant public papers documenting the history of Massachusetts. “One of the rioters declared that the first places which they looked into were the beds, in order to murder the children,” according to Peter Oliver. “All this was joy to Mr. Otis, as also to some of the considerable merchants who were smugglers and personally active in the diabolical scene.”

7

It took the mob three hours to dislodge the cupola from the roof, and only fatigue and the rising sun put an end to the systematic destruction they wreaked on the Hutchinson home. “If the Devil had been here last night,” one Bostonian commented the next day, “he would have gone back to his own regions ashamed of being outdone and never more have set foot upon the earth.”

8

In the course of the following day, rumors swirled through Boston that the mob had a list of fifteen “prominent gentlemen” and contemplated “a war of plunder, of general leveling and taking away the distinction of rich and poor.”

9

Fearful that his name might be on the list, Hancock joined other Boston selectmen in refusing to bring the looters to justice. The Governor convened the Council, the upper house of the state legislature, in the safety of outlying Cambridge. They agreed that the previous night's rioting

“had given such a turn to the town that all gentlemen in the place were ready to support the government in detecting and publishing the actors in the last horrid scene.”

10

Although the Council issued a warrant to arrest Mackintosh, Sam Adams led a group that demanded and won his release. After others were jailed, a mob broke into the jailer's house, seized his keys, and released the prisoners before they could be tried. They never were.

By the end of September, events continued isolating John Hancock. Only the wealthiest merchants and men of great propertyâa tiny eliteâremained united behind the royal governor. The base of those in opposition had broadened to include a sizableâand most respectableâmajority that included almost all of Boston's small merchants and shopkeepers; its printers, tavern owners, land speculators, and smugglers; a few of its ship owners; and many ordinary citizens who worked for the merchants, shopkeepers, printers, and so forth. All would have to pay stamp taxes on everything from playing cards to wills. For most, it would have been the first direct tax they had ever had to pay, although all paid indirect, hidden taxes such as customs duties, which merchants tacked onto wholesale and retail prices.

Publicly, Hancock sided with no one, and when a vacancy occurred in the House of Representatives, voters rejected him brusquely. He finished last on the list of candidates with a mere forty votes. Instead, they elected the outspoken James Otis and his friend Sam Adamsâdespite the prison term hanging over Adams's head for embezzling public monies. As titular leaders of the radical majority, Otis and Adams used veiled threats of mob retaliation to gain control of every important committee in the House of Representatives. As Governor Bernard noted with dismay, the “faction in perpetual opposition to Government” took complete control. “What with inflammatory speeches within doors and the parades of the mob without,” the Otis-Adams radicals “entirely triumphed over the little remains of government.”

11

Hancock thus remained in a precarious position on the fence around his hilltop mansion. Rather than put his property and personal safety at risk, he spent more time within sight of his home at the nearby Merchants Club and at the Green Dragon Tavern, where his fellow Freemasons assembled. Although most of the Green Dragon Freemasons were wealthy Har vard alumni, they did not exclude less-schooled applicants or skilled

craftsmen such as Paul Revere. The son of a silversmith of Huguenot descent, the younger Revere had eschewed higher education in favor of an apprenticeship in his father's shop and eventual ownership of their prosperous enterprise. Sam Adams was not a Freemason, but he stopped at the Green Dragon Tavern on the daily rounds he made of Boston taverns, coaxing and cajoling imbibers to support his quest for political power. Step by step, tavern by tavern, he assumed leadership over the disparate elements of Boston's malcontentsâthe small merchants facing bankruptcy, the skilled artisans struggling to keep their shops open, and those out-of-work laborers who were too poor to feed their children or heat their hovels. Nor did he overlook any Green Dragon Utopiansâthe rich sons of Harvard who had studied and believed in the principles set forth in the works of John Locke, Voltaire, Rousseau, and others.

According to his cousin John Adams, Sam Adams had the most thorough understanding of “the temper and character of the people” along with a gift for intellectual seduction.

Although erudite, he spoke the common tongue and dressed in the common clothânot miserable, but as a working artisan, say, after a day's work. Everywhere he went, in every tavern, on the streets, he recruited ceaselessly for his rebellion against royal rule and those who had destroyed his father. He made it his constant rule to watch the rise of every brilliant genius, to seek his acquaintance, to court his friendship, to cultivate his natural feelings in favor of his native country, to warn him against the hostile designs of Great Britain.

12

His tactics varied with each recruitâflattery for one, cajolery for another, pledges and promises for another. From the moment he stepped into the General Court, he began organizing a group of powerful allies from rural districts to expand his political power beyond Boston to the rest of the province.

Although he could count on a broad-based throng of rebels and wealthy young malcontents, Sam Adams had failed to recruit anyone from the merchant elite, and he knew he would never overturn the royal governor without the political and financial support of at least a few merchant-aristocrats

to buy arms, ammunition, and rum for the mobs. His cousin John Adams called Sam a “designing person” who, in public, “affects to despise riches, and not to dread poverty, but no man is more ambitious.”

13