Zeely (5 page)

Authors: Virginia Hamilton

“Zeely!” Geeder shouted. “Aren’t you going to move the animals today?” Her voice surprised her. It was quite loud in the quiet field.

Geeder never found out what Zeely answered. Zeely had turned toward her when an unearthly squeal came from Uncle Ross’ barn. Zeely walked over to the broken fence and weighted it down with heavy rocks so that the smaller pigs couldn’t root under it. Then she made her way from the field, swinging the gate closed behind her. She headed down Leadback Road, passed Uncle Ross’ house and did not look to the left or to the right. Geeder watched her go out of sight, wondering about her, hoping she would turn around. Zeely didn’t do anything more than walk away down the road.

When Toeboy and Geeder reached the barn, they found Uncle Ross filling in a hole he had dug.

“What’s that hole for?” Toeboy asked.

“Entrails of the sow,” Uncle Ross said. Seeing Geeder’s questioning face, he motioned her and Toeboy toward the barn door. “You’ll find her in there,” he said.

Inside the barn, they found the sow. “Why, they’ve butchered her!” Geeder said. The sow was already skinned and hanging high overhead on an oak crossbeam. The carcass was bloody red. Geeder had to turn her face away.

“I hope I don’t have to eat any of that,” Toeboy said. He gulped hard, for the sight of the raw meat made him sick.

“Oh, I couldn’t eat it, I just couldn’t!” Geeder said.

“You two get away, now,” Uncle Ross said, coming up behind them. “Go to the shed where there’s something for you to do.”

“But I want to see Mr. Tayber move his hogs,” Geeder said.

“Well, he won’t be moving them today,” said Uncle Ross. “Too much time lost because of the sow. He’ll have to move them tomorrow. You go on to the shed. There’s plenty for you to do there.”

The day before, Uncle Ross had told them what he wanted them to do in the shed. They were to stack magazines and catalogs in neat bundles and tie them so they could be carted away. Geeder and Toeboy were more than glad to leave the barn. They rushed out into the sunlight, leaving the sad carcass of the sow and the memory of it behind.

Geeder had an odd feeling whenever she entered the shed. It was cool and shadowy, always. Both she and Toeboy were barefoot and the earthen floor of the shed felt clean and fresh. The whole place made whispering seem quite natural. The roof was louvered boards, over which a large tarpaulin was fastened in bad weather. Today, the tarpaulin was folded away and long stripes of sunlight slanted to the floor. The sun got tangled in dust and cobwebs and glowed in dark corners. All was still. What little noise Geeder and Toeboy made was muffled, fading quickly. They took a good look around before settling down to work.

They sat close together. Toeboy stacked the catalogs, and Geeder had the magazines.

“I love going through old pictures,” Geeder said. “It’s the best fun of anything.”

“It’s not fair,” Toeboy said. “You could let me have some of the magazines.”

“Well, you can’t have any,” Geeder said. “Just do what you’re supposed to and be quiet about it.”

Toeboy was mad enough at Geeder to hit her. But he knew she would start a fight if he did and she would probably win, too. He contented himself with the catalogs. He had two bundles of fifty stacked and tied before Geeder had stacked any magazines.

“You’re not supposed to read them,” he told her. “That’s not fair at all.”

“I’m just looking at the pictures before I stack them,” she said.

“You’d better not let Uncle Ross catch you.”

“You worry so much about nothing!” Geeder said.

“I believe I’ll just go tell Uncle Ross,” Toeboy said. He got up, heading for the door. Geeder smiled after him and continued turning the glossy pages of a magazine.

Toeboy stood at the corner of the shed. He waited for Geeder to come after him but she didn’t. He stood, fidgeting and trying hard to be quiet. Finally, he came back inside. He knew instantly that something was wrong.

Geeder bent low over a magazine. On her lap were two more magazines that slowly slid to the floor. She pressed her hand against the page, as if to hold on to what she saw there. Then, she sat very still and her breath came in a long, low sigh.

“Geeder?” Toeboy whispered. “I’m not going to tell. I was only teasing you.”

She didn’t hear him. He crept up beside her and tried taking the magazine from her, but she wouldn’t let it go. He looked over her shoulder. What he saw caused him to leap away, as though he had seen a ghost.

“I knew it all the time! I knew it!” Geeder said to him.

Geeder had found something extraordinary, a photograph of an African woman of royal birth. She was a Mututsi. She belonged to the Batutsi tribe. The magazine Geeder held said that the Batutsis were so tall they were almost giants. They were known all over the world as Watutsis, the word for them in the Swahili language. Except for the tribal gown the girl wore and the royal headband wound tightly around her head, she could have been Zeely Tayber standing tall and serene in Uncle Ross’ west field.

Toeboy carefully read what was written under the photograph of the African girl. “Maybe Zeely Tayber is a queen,” he said at last.

Geeder stared at Toeboy. It took her a few seconds to compose herself enough to say, “Well, of course, Toeboy—what do you think? I never doubted for a minute that Miss Zeely Tayber was anything else!”

She was quiet a long while then, staring at the photograph. It was as if her mind had left her. She simply sat with her mouth open, holding the picture; not one whisper passed her lips.

Uncle Ross happened by the shed. He didn’t see Geeder and Toeboy at first, they sat so still in the shadows. But soon, his eyes grew accustomed to the darkness of the shed as he peeked in and he smiled and entered. Geeder aroused herself, getting up to meet Uncle Ross. She handed him the magazine without a word. Uncle Ross carried it to the doorway; there, in the light, he stood gazing at the photograph. His face grew puzzled. Geeder was to remember all day and all night what he said at that moment.

“The same nose,” he muttered, “those slanted eyes . . . black, too, black as night.” He looked from the photograph to Geeder, then to Toeboy and back to Geeder again. “So you believe Zeely Tayber to be some kind of royalty,” he said, finally.

“There isn’t any doubt that Zeely’s a queen,” Geeder said. Her voice was calm. “The picture is proof.”

“You may have discovered the people Zeely is descended from,” Uncle Ross said, “but I can’t see that that’s going to make her a queen.” He was about to say more when he noticed Geeder’s stubborn expression. He knew then that anything he might say would make no difference. He left the shed without saying anything else. And when he had gone, Geeder danced around with the photograph clutched in her arms. Toeboy hopped on one foot the length of the shed.

“Oh, it’s just grand,” Geeder said. “Everything was left to me and I took care of it all by myself!”

THAT AFTERNOON, GEEDER STAYED

in her room gazing at the photograph of the Watutsi woman. Toeboy disappeared right after lunch and Uncle Ross had business in the village. Geeder studied the picture from a distance, from up close and from every angle. She sat stiffly in one of the cherry-wood chairs in her room, running her hands slowly over its arms. Her heart beat so fast she felt she would faint.

Soon, she tried standing as straight and tall as the woman in the photograph stood. But she didn’t feel right standing that way.

“My neck isn’t long enough,” she said. “My arms are too short.”

Geeder stretched out on her bed and looked out through the luster and glitter of her beads. She saw herself, tall and very thin, walking with Zeely Tayber. They were sisters. They looked so much alike that people sometimes called her Zeely. Zeely Tayber was queen but she liked having Geeder always at her side. Anytime people wanted to talk with Zeely, they first had to speak with Geeder. She would listen and then she would give Zeely a sign and Zeely would understand. Zeely could not talk to anyone but Geeder, that was the law of the land. One night Zeely was very sick. Everyone thought she surely would die. It was Geeder who got her well again in just one week. And then, Zeely was so happy, she made Geeder queen.

“Queen,” Geeder said, out loud. She turned on her side so she could see the photograph of the Watutsi woman.

“It’s a pretty picture,” she said. “It’s about the nicest picture I’ve ever seen.”

By suppertime, Toeboy had returned to the farm. Uncle Ross had come home, too, and he prepared a wonderful dinner for them. There was baked chicken allowed to cool, sweet potatoes, beans from the pantry and a salad of fresh vegetables from the garden. By suppertime, also, Geeder had made up her mind about something. She had never gone to any of the bonfires the children were fond of having. They loved nothing better than dried weeds and corncobs smoking high and burning bright. They danced and sang around the flames until they were too tired even to sleep.

There was to be a bonfire tonight. This time, she would go. She ate quickly and spoke little, saying just enough to let Uncle Ross know that the sweet potatoes were fine. She just couldn’t get enough sweet potatoes, she told him.

“Can Geeder and I go to Bennie Green’s house this evening?” Toeboy asked right after they had finished eating. Beyond Bennie’s back yard was an empty lot where the bonfire would be. Nearly all the children of the farms and the town were going to be there.

“I’ll let you go,” Uncle Ross said, “but you must be home by eleven o’clock.”

“Oh, Uncle Ross!” Toeboy pleaded. “The sky doesn’t even turn dark until after nine—that’s no time at all!”

“No good bonfire can blaze good if the sky isn’t black,” Geeder said.

Uncle Ross thought a minute. “Twelve o’clock, then,” he said, “but no later. And be careful of the flames. Don’t get smoke in your eyes!”

He knew they would come home with their clothing singed; their skin and hair would smell of smoke for days to come. But Archibald Green, Bennie’s father, would keep a sharp eye out so that none of the children would harm themselves.

NINE FIFTEEN, AND THE

sky was deepest black with a moon full and red above the fields.

“Look what’s walking along with us,” Toeboy said. The moon was so clear that Geeder and Toeboy cast shadows as they hurried along Leadback Road.

“I can hear the kids at the bonfire,” Geeder said, “and we still have a long way to go.”

They could see the bonfire. It lit up all the houses and trees in that part of town where Bennie Green lived. Soon, they left Leadback Road to shortcut through back yards, following fence lines directly to the bonfire.

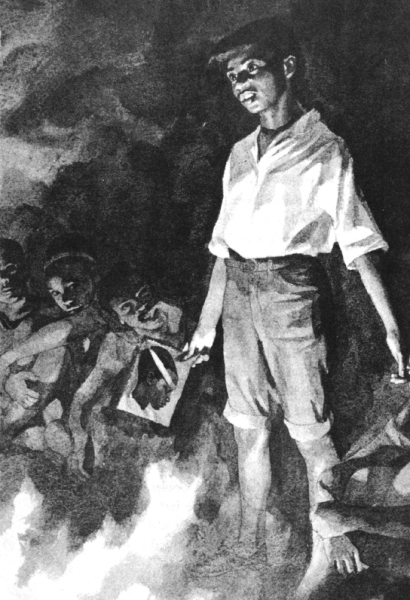

The children ranged around the fire. They were bright Indians; some had feathers in their hair. Here, a face was weirdly lighted, and there, a whole figure emerged only to become lost in shadow as though it had never been. As Geeder and Toeboy climbed the last fence, a green and gold stream of sparks rose high above the flames.

“Isn’t that pretty!” Geeder whispered. “Why, everything is just beautiful for Zeely and me!”

Bennie Green came over to greet Geeder and Toeboy and so did some of the other children.

Geeder wore ten strands of glass beads of every color, shape and size. The flames reflected in the glass, causing her neck to seem encircled by stars. The girls greatly admired the necklaces, as they did Geeder. They had seen her before, but she hadn’t often played with them; that was why they were somewhat shy with her. She was different, that was all. She lived away in a city and they believed she must know a great many things. This night, Geeder was nice to them.

“You can take turns wearing my necklaces,” she said.

This pleased the girls, and Geeder, too.

When the bonfire died down to a few feet above the coals, Bennie Green passed out two hotdogs, two buns and a stick to each person. There was lemonade to drink and soon all of them were busy eating. The girls bunched together right next to the boys. Geeder got talking about Zeely Tayber. Before she knew it, she was telling a story. Even the boys listened to her.

She was aware of the silence around her and saw the darkness within the trees, where the bonfire could not penetrate.

“Zeely Tayber is a queen,” she said, “and this picture I found is her grandmother as a girl.”

Toeboy acted as though he wanted to say something. Geeder gave him a hard look so he wouldn’t utter a word. From her pocket, she brought out the photograph of the Watutsi woman. It was passed from hand to hand, with the girls and boys leaning close to the fire to see it.

“I bet Miss Zeely looks exactly like her mother,” Geeder said. “And her mother looked just like

her

mother, and on and on, clear to Africa, where it all began.”

Geeder was interrupted by a boy called Warner. He was tall and thin, taller than the other boys. He stood up, hopping back and forth on one foot. “I know about Watutsis,” he said. “They come from a place once called Ruanda-Urundi. It has a new name now because it’s a new nation. I know all about them and they are bad people. They keep people as slaves!”

The boys and girls sat silently, looking from Warner to Geeder. Geeder said that she didn’t believe him, that he must have made the whole thing up. But Warner wasn’t to be taken lightly. He told a sad tale of the troubles of the Watutsis. He said that their former slaves had risen to fight them, that soon there might not be any Watutsis.

“Well,” said Geeder, “you shouldn’t speak mean of them if they’re being hurt. Anyway, I don’t see what that has to do with Zeely. She’s still the same. She’s still a queen!”