Your Face Tomorrow: Poison, Shadow, and Farewell (61 page)

Read Your Face Tomorrow: Poison, Shadow, and Farewell Online

Authors: Javier Marías,Margaret Jull Costa

My wife Valerie's German, for example, was impeccable, without a trace of accent. No, that wasn't the reason, Jacobo. I may have had only a very brief experience of your War, but I felt that hatred when I was in Spain. It was a kind of all-embracing hatred that surfaced at the slightest provocation and wasn't prepared to consider any mitigating factor or information or nuance.

An enemy could be a perfectly decent person who had behaved generously towards his political opponents or shown pity, or perhaps even someone completely inoffensive, like all those schoolteachers who were shot by the beasts on one side and the many humble nuns killed by the beasts on the other. They didn't care. An enemy was simply that, an enemy; he or she couldn't be pardoned, no extenuating circumstances could be taken into consideration; it was as if they saw no difference between having killed or betrayed someone and holding certain beliefs or ideas or even preferences, do you see what I mean? Well, you'll know all this from your father. They tried to infect us foreigners with the same hatred, but, needless to say, it wasn't something that could be passed on, not to that degree. It was a strange thing your War, I don't think there's ever been another war like it, not even other civil wars in other places. People lived in such close proximity in Spain then, although it's not like that now'—'Yes, it is,' I thought, 'up to a point.' 'There were no really big cities and everyone was always out in the street, in the cafes or the bars. It was impossible to avoid, how can I put it, that epidermal closeness, which is what engenders affection but also anger and hatred. To our population, on the other hand, the Germans seemed distant, almost abstract beings.'

That mention of his wife, Val or Valerie, hadn't escaped me, but I was even more interested in the fact that, for the first time, he should refer openly to his presence in my country during the War; it wasn't that long since I had first found out about his participation, of which he had never spoken to me before. I looked at his suddenly gaunt face. 'Yes, his features have grown sharper and he has the same look in his eyes as my father,' I thought or regretfully acknowledged, 'that same unfathomable gaze'; and it occurred to me that he probably knew he did not have much more time, and when you know that, you have to make definitive decisions about the episodes or deeds which, if you tell no one, will never be known. ('It's not just that I will grow old and disappear,' poor, doomed Dearlove had said in Edinburgh, 'it's that everyone who might talk about me will gradually disappear too, as if they were all under some kind of curse'; and who could say any different?) It is, inevitably, a delicate moment, in which you have to distinguish once and for all between what you want to remain forever unknown—uncounted, undiscovered, erased, nonexistent—and what you might like to be known and recovered, so that whatever once was will be able one day to whisper: 'I existed' and prevent others from saying 'No, this was never here, never, it neither strode the world nor trod the earth, it did not exist and never happened.' (Or not even that, because in order to deny something you have to have a witness.) If you say absolutely nothing, you will be impeding another's curiosity and, therefore, some remote possible future investigation. Wheeler must, after all, have remembered that on the night of his buffet supper I had asked him by what name he had been known in Spain, and that, had he told me, I would have immediately gone to look up that name in the indexes of all his books, in his War library, on his west shelves, and later on in other books as well. In fact, he was the one who had put the idea in my head, it hadn't even occurred to me until then: perhaps he had done so out of mere congenital pride and vanity, or perhaps, more deliberately, so that having once inoculated me with the thought, I would not be satisfied and would not let go of my prey, something which, as he knew perfectly well, I, like himself and Tupra, never did. Perhaps now he was ready to give me a few more facts and to feed my imagination before it was too late and before he would cease to be able to feed or direct or plot or manipulate or shape anything. Before he was left entirely at the mercy of the living, who are rarely kind to the recent dead. 'That's asking an awful lot, Jacobo,' he had said then in reply to my direct question. 'Tonight anyway. Perhaps another time.' Maybe that 'other time' had come.

'What did you do in Spain during the Civil War, Peter?' I asked straight out. 'How long were you there? Not long, I imagine. Before, you told me that you were just passing through. Who were you working with? Where were you?'

Wheeler gave an amused smile as he had on that earlier night, when he had played with my newly aroused curiosity and said things like: 'If you'd ever asked me about it . . .But you've never shown the slightest interest in the subject. You've shown no curiosity at all about my peninsular adventures. You should have made the most of past opportunities, you see. You have to plan ahead, to anticipate.' He raised his hand to the back of his armchair and felt around without success. He wanted his walking stick and couldn't find it without turning round. I stood up, grabbed the stick and handed it to him, thinking he was going to use it to help him get to his feet. Instead, he placed it across his lap or, rather, rested the ends on the arms of his chair and gripped the stick with both hands, as if it were a pole or a javelin.

'Well, I went twice, but on both occasions I was there only briefly,' he said, very slowly at first, as if he did not entirely want to release the information or the words; as if he were forcing his tongue to anticipate his actual decision, the not entirely definite decision to tell me all: he might want to tell me, but, as he had explained with some embarrassment, he might not yet be authorized to do so. 'The first time was in March of 1937, in the company of Dr. Hewlett Johnson, whose name will mean nothing to you. However, you might be familiar with his nickname, "the Red Dean," by which he was known then and later.' We were speaking in English. Of course I knew the name, of course I had heard of it. In fact, I could scarcely believe it.

'El bandido Deán de Canterbury!'

I exclaimed in Spanish. 'Don't tell me you knew him.'

'I beg your pardon!' he said, momentarily disconcerted by that sudden intrusion in Spanish and by that strange way of referring to the Dean as 'the bandit Dean of Canterbury'

'As you may well remember from what I've told you before, my father was arrested shortly after the end of the Civil War. And several false accusations were made against him, one of them, as I've often heard him say, was that he had been "the willing companion in Spain of the bandit Dean of Canterbury." Imagine! That strange cleric was very nearly responsible—albeit indirectly, unwittingly and involuntarily—for my not being born, nor any of my siblings either. I mean that in the normal course of events my father would have been summarily condemned and shot; they came for him in May, 1939, only a month and a half after the Francoists entered Madrid, and in those days if you denounced someone, even if you did so as a mere private individual, you didn't have to prove their guilt, they had to prove their innocence, and how could my father possibly have proved that he had never in his life seen that Canterburian Dean' (I was speaking in English again and so didn't need to resort to the strange Spanish equivalent

'cantuariense')

'or the falsity of the other charges, which were far graver. He was immensely lucky, and after a few months in prison was acquitted and released, although he suffered reprisals for many years afterwards. But imagine . . .'

'It's certainly a striking coincidence,' Wheeler said, interrupting me. 'Very striking. But let me continue my story, otherwise I'll lose the thread.' It was as if he thought the coincidence to be of no importance, as if he felt coincidences to be the most natural thing in the world, as did Pérez Nuix and I myself. Or perhaps, I thought, he had been planning his next encounter with me for a while, hoping that it would happen, and that I would deign to go and see him, and so knew exactly what he was going to tell me, what partial information he was going to give me, and did not want to be forced to depart from his script by impromptu remarks or distractions or interruptions (he never lost the thread). He may not have wanted any interruptions, but he would have to put up with at least one, when I told him what had happened to Dearlove and demanded, if not an explanation, at least some pronouncement on Tupra's behavior. And so he set my father aside and continued, still slowly, rather like someone reciting something they have previously memorized. 'We were the first to break the naval blockade set up by the Nationalists (I always thought it scandalous that they should call themselves that) in the Bay of Biscay. We set sail from Bermeo, near Bilbao, in a French torpedo boat, and reached Saint Jean de Luz without mishap, despite the widespread and widely believed rumors that the whole area had been mined. That was a Francoist lie, and a very effective one, because it kept boats away and stopped provisions reaching the Basque Country. The Dean described the crossing in

The Manchester Guardian

and a few days later, a merchant vessel, the

Seven Seas Spray,

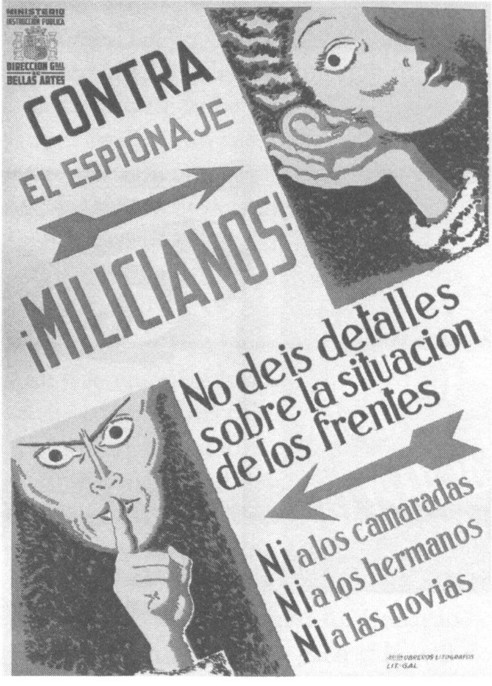

tried its luck in the other direction, leaving Saint Jean de Luz after dark. And the following morning, when it sailed up the river to the dock in Bilbao, having encountered neither mines nor warships en route, the people of Bilbao massed on the quay and cheered the Captain, who was standing on the bridge with his daughter, and cried: "Long live the British sailors! Long live Liberty!" It was terribly moving apparently. And we paved the way. It's just a shame we were going in the other direction. The Captain was called Roberts.' Wheeler, eyes very wide, paused for a moment, deep in thought, as if he were reliving what he had not actually lived through, but of which he felt himself, in part, the artificer. Then he went on: 'Before that, we'd witnessed the bombing of Durango. We missed being caught in it ourselves by about ten minutes, it happened when we were approaching by road. We saw it from a hillside, in the distance. We saw the planes approaching, they were Junkers 52s, German. Then we heard a great roar and a vast black cloud rose up from the town. By the time we finally drove into the town after nightfall, the place had been almost completely destroyed. According to the first estimates, there had been some 200 civilian deaths and about 800 wounded, among them two priests and thirteen nuns. That same night, Franco's general headquarters announced to the world by radio that the Reds had blown up churches and killed nuns in Durango, in the devoutly Catholic Basque Country, as well as two priests while they were saying mass, one when he was giving communion to the faithful and the other while elevating the Host. All of this was true: the nuns had died in the chapel of Santa Susana, one priest in the Jesuit church and the other in the church of Santa Maria, but they had been bombed, as had the Convento de los Augustinos. I remember the names or those were the names I was given. It wasn't the Reds who had done it, though, it was those Junkers 52s. That was on March 31".'—He fell silent for a moment, a look of anger on his face, as if he were feeling the anger he had felt then, some seventy years before. 'That was what your War was like. One lie after another, every day and everywhere, like a great flood, something that devastates and drowns. You try to take one apart only to find there are ten new lies to deal with the next day. You can't cope. You let things go, give up. There are so many people devoted to creating those lies that they become a tremendous force impossible to stop. That was my first experience of war, I wasn't used to it, but all wars are full of lies, they're a fundamental part of them, if not their principal ingredient. And the worst thing is that none are ever completely refuted. However many years pass, there are always people prepared to keep an old lie alive, and any lie will do, even the most improbable and most insane. No lie is ever entirely extinguished.'

'That's why one shouldn't really ever tell anyone anything, isn't that right, Peter?' I said, quoting his words. It was what he had said to me just before lunch, on the Sunday of that now far-off weekend, while Mrs. Berry was waving to us from the window.

He didn't remember or didn't realize I was quoting him, or else he simply ignored it. He stroked the long deep scar on the left side of his chin, a gesture I had never seen him make before: he didn't usually touch or mention that scar, and so I had never asked him about it. If it did not exist as far as he was concerned, I had to respect that. I assumed it was from the war.

'Oh, I learned to lie as well, later on. Telling the truth isn't necessarily better, you know. The consequences are sometimes identical.' However, he didn't linger over that remark, but continued talking in this rather schematic manner, as if he had already drawn up a narrative plan for that day, that is, for the next time I went to see him. 'We were briefly in Madrid, Valencia and Barcelona, and then I came back to England. My second visit took place a year later, in the summer of 1938. On that occasion, my guide, or rather my driving force, was Alan Hillgarth, the head of our Naval Intelligence in Spain. Although he spent most of his time in Mallorca (in fact, his son Jocelyn, the historian, was born there, you've heard of him I expect), he gave me the task of watching and monitoring the movements of Francoist warships in the ports around the Bay of Biscay, on the assumption that I had acquired some knowledge of the area. Most, of course, were German and Italian ships, which had been harassing and attacking the British merchant fleet in 1936, both there in the Bay of Biscay and in the Mediterranean, and so the Admiralty was keen to gather as much information as possible about what kind of ships they were and their positions. I was traveling in the guise of a university researcher, on the pretext of delving into and rummaging around in Spain's old and highly disorganized archives, and I did exactly that—indeed some of the discoveries I made as a specialist in the history of Spain and Portugal date from that period: in fact it was in Portugal, when I was eventually deported there, that I started preparing my thesis on the sources used by Fernão Lopes, the great chronicler of the fourteenth century whom I'm sure you know' The truth is I'd never heard of him. 'But that's by the by. I was arrested by the Guardia Civil when I was on the Islas Cies, taking photographs of the cruiser

Canarias,

one of the few ships in the Spanish navy that had gone over to the rebels, as the Republicans called the Nationalists. They searched me, of course, and found compromising material, mainly photographs. Normally, as you can imagine, they would have executed me. We were, after all, in the middle of a war.' Wheeler paused. He may have been telling his story in that rather mechanical way, almost as if it had happened to someone else, but he nevertheless knew when to prolong the uncertainty.