You Only Get One Life (26 page)

Read You Only Get One Life Online

Authors: Brigitte Nielsen

The clinic had a postage stamp-sized outside area which was the only place you could go for fresh air or to have a cigarette. We were like animals held in a small enclosure at the zoo. Some of the other women looked so close to death that if they made it through treatment, it was obvious they wouldn’t see their next birthday. That was a wake-up call for me – I felt I was on the same road. Those who were doing heroin and other substances died so much more quickly than many alcoholics. The memories of the people I met there will always be imprinted in my mind.

I was issued with a military-style blanket to sleep under and at 7am on the dot we all had five minutes to jump out of bed, make it, get dressed and have our shoes out from under the bed and on. Our closet areas had to be clean enough to pass a thorough daily inspection and we then waited to be taken to breakfast. It was served in the cafeteria, where we lined up with a tray before eating in total silence. Though the Valium helped me sleep, my nights were disturbed by the screams of the three girls who shared the room with me. It was like being in an asylum. They would do strange things and I was constantly worried that they would attack me or the staff.

The days passed monotonously: I began to eat small amounts of food along with the drugs that I guess were used to flush out my system. I felt sorry for myself all over again – I had time to ask myself how I had ended up there – and that was really the start of my treatment. One of the other patients I talked to was a young guy who had been on drugs

for as long as he could remember. He freaked out when his mother died and ended up in treatment. His father was never around but he was a really nice boy and I got to know quite a lot about him. Three months after I left the rehab he died of an overdose: he was 22.

My Valium was withdrawn after those first five days, but I was still not permitted any contact with the outside world – not even with Mattia. I was tired of the whole thing, it was ridiculous. I’d been doing really well surrounded by all these crazy people and they still wouldn’t even allow me five minutes with Mattia; I was sure I didn’t need to stay there any longer.

‘You’re free to go any time you want,’ they said, ‘but if you leave before your treatment is finished then your insurance won’t cover it.’

‘I don’t care – I need to go, I’m over it. There are too many people here and I can’t adapt to this way of life. They’re criminals – murderers, drug users. They’re ten times worse than me!’

‘Of course, Brigitte,’ they said. ‘If that’s what you want to do. Go ahead and do your thing. Try not to misuse alcohol again and remember about the insurance. And, by the way, if you leave under these circumstances you can never come back again.’ It was said politely but very firmly and I knew that they meant it. I stayed.

The first task each day after breakfast was to clean the bathrooms and the kitchens, wash the floors, wipe the windows and tidy up the communal areas. People who had been there the longest got to allocate the tasks, the worst of

which was the bathrooms. With a pair of heavy rubber gloves on I would get down on my knees in the showers and as I scrubbed at the shit and vomit, I would think back to my million-dollar home in the Hollywood Hills. All the high points of my life flashed in front of me as I tried to get rid of the stench – the marriage to Sylvester, the movies, the albums… whatever.

Mornings continued with a 12-step plan meeting, the system for recovering users made famous by Alcoholics Anonymous. We discussed our thoughts in a group and shared progress in our treatment. While some of it was helpful for me, I didn’t get along with the way it seemed to cover every last aspect of your life. It might be perfect for a lot of people but for me it had overtones of brainwashing. These days I don’t go to AA meetings as many times as it was suggested I should, but I realised then – and I still know it now – that I was a user and I will remain one for the rest of my life.

Specialist doctors would say that it’s part of the sickness that I would prefer to have dinner with Mattia than go to nightly AA meetings, but I couldn’t do it. Yet the sessions did provide the tools to make me sure my life won’t get stuck again. I guess what I’m saying here to people who have faced similar situations is that you have to find your own way – listen to what they say in rehab, but whatever you do – go for it.

Lunch would be followed by gruelling sessions with a psychiatrist and while we weren’t allowed to listen to music or watch TV there were occasionally movies. Anyone hoping for escapism would be disappointed as it would

always be a documentary about alcoholism or drug use.

I was assigned a case worker, who kept detailed notes of every conversation we had. She was always very frank with me when she assessed how long she thought I would be staying in the clinic. I found it all very depressing: every day followed the same routine. Back in the dorm room one of the girls would be sitting on her bed staring vacantly into space; another would be crying out in her sleep. It was relentless and it was devastating to see girls 20 years younger than me look as if they were completely done. I said to myself, ‘Take a good look around you, Gitte. Thank God you got help in time.’ And to think I hadn’t wanted to do it.

The biggest crisis I faced during my stay was on my birthday: I was frightened, lonely and miserable. I begged them to let me have just a five-minute call with Mattia. Even 30 seconds hearing his voice would have made everything seem okay.

‘There’s a phone box on the other side of the street,’ they said. ‘You can use that – but when you walk out and close the door you aren’t coming back. If you feel you need to call him, then you have to forget about what you’re doing here.’ My 43rd birthday was spent with desperately ill alcoholics listening to the constant, strange wailing of the narcos; that was the worst. I don’t know what it was, whether it was something they’d taken with their heroin, but they never stopped yelling.

Perhaps because I was in better shape I became a focal point for the treatment group. I don’t want to say I was a leader, but I sort of carried them with me. That opened up something in me as I was able to compare my own, terrible

stories with those that were often far worse. We were all really fucked up but they also supported me too. The biggest difference between us was that almost all of them had nowhere to go when they were done with their treatment at the centre. No friends, no family. When things got tough for me I would tell myself that if I couldn’t make it in here, I might as well lie down and die because I had Mattia, my kids, my mother and my girlfriends all waiting for me.

The other women could only look forward to getting out to be greeted by the men who wanted to get them into prostitution, get them back on drugs and use them to do crime. Most of them had children of their own by the time they were 16. I thought about my own unhappiness as a child and how privileged I’d been in reality. There I was saying how terrible it was to be laughed at as a kid and how that had thrown a shadow over my life, but there was really no comparison to what these girls endured. Not surprisingly, as the others there began to get clearer, they wanted to stay in the clinic for as long as possible. There they were safe, but there was nothing provided on the outside.

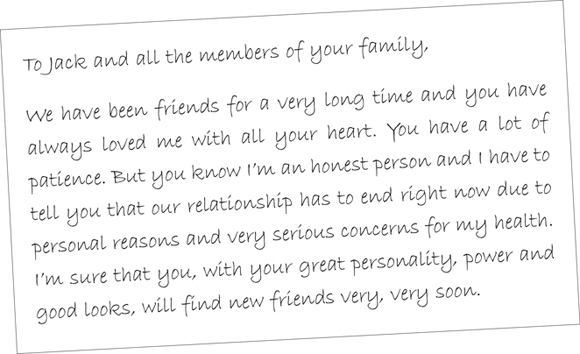

In meetings with the psychiatrist I explored what had gone wrong for me but I didn’t find it easy to open up – I think my fear was all about this being the first time that I had really been worked on to let out my demons. I was allowed the time to let go without the feeling that there were always people watching what I was doing. The exercises included writing a farewell letter to my father and another to my sickness. I decided to address that one personally to a bottle of Jack Daniel’s:

The staff at the clinic patiently worked to untangle the knot in my stomach. And even though I found many of the sessions to be hard work, I really wanted to succeed. It wouldn’t have happened any other way; I couldn’t have resisted the treatment and kept sober.

Now I don’t think I’ll have to see a psychiatrist for the rest of my life but I know that the AA meetings will be a constant if occasional presence. It’s so helpful to have other people to talk to about my problems and the future. Besides, I love to hear other stories and to learn about the situations that people have found themselves in. It helps to broaden my own perspective and it will always be important for me to think about what I am, even though I haven’t drunk anything since 2007. I still think about it every day and I have slipped a couple of times, but even when I do, it doesn’t mean the work I do on myself isn’t still meaningful or that I won’t reach a solution. My problem will always be a part of my life and I will always be aware of it.

THE LAST HURDLE

T

he 14 days I spent in treatment felt more like 14 years. Even then I knew that the process of getting clean had only just begun and that I would have to watch myself carefully when I left. The treatment was supposed to take three months but even though they warned against thinking about life outside, I had work to do.

I was beginning to question all my assumptions about myself. Have you ever thought that the person you have to spend the longest time with is yourself? There will never be anyone closer to you than you are to yourself, but can you honestly say you’re your own best friend? Do you talk to yourself every day? Do you know yourself as well as you should? Probably not. There are few of us who can talk about who we really are. Those were the thoughts that occupied me when I left.

In my marriage I had been my own worst enemy: I didn’t listen to myself and I didn’t support myself when I needed

to. It was only me that could do it and it was only me who made sure it didn’t happen. I got frustrated with myself, I blamed myself for not doing more and I was never sympathetic in the way I would have been had I been talking to a friend about her own problems.

When I thought about it I had to admit that I had never really been good to myself: we let ourselves down before we let anyone else down. In the end it got so bad for me that I almost lost everything. It might sound as if I think I know it all now, but that’s the only way I can explain what happened to me.

If we want to live in harmony with ourselves, we need to find out who we are. You have to be painfully honest with yourself, you have to have the guts to look at who you really are rather than the person you would like to be. Can you list your own strengths and weaknesses and allow yourself to say them out loud to yourself? You have to stand by each aspect of your character, no matter what happens. That’s what I mean when I say you need to be your own best friend.

When I came out I had to admit that I had no idea who I was or how I felt. Given that, there was no way I could look after myself – that’s why I didn’t have the strength and wisdom to know when to have fun and when to stop. I felt as raw as if layers of me had been peeled away, but I knew what my responsibilities were and that the next stage was to act on them. I would need help because I was, deep down, unhappy and I knew my cravings for alcohol wouldn’t disappear just like that.

I faced my first major test the day I left. Foofie Foofie – aka Flavor Flav – had asked me to be a guest on

The

Comedy Roast

. This was the Comedy Central programme that affectionately mocked its stars and because we’d got on so well, Foofie had asked me to sit on the panel alongside the likes of Snoop Doggy Dogg, Ice-T and assorted comedians. The shows always descended into the meanest digs you could imagine. It was great fun to be part of it, to see Foofie again and to meet his friends, but there was also an uncomfortable side of it for me, being surrounded by drink and everyone trying to get me to take part. ‘Hey Foofie, I’ve just literally yesterday got out of rehab,’ I told him. They all congratulated me but within minutes I was being offered alcohol. ‘No, thanks, I don’t want to get back into that again.’ I wasn’t angry so much as disappointed. Were they really my friends? I wasn’t suggesting that they didn’t drink, but I didn’t expect them to tempt me off the wagon.

That said, it was much easier to be open about going to rehab in the US. Celebrities were more proud of doing it than their equivalents in Europe. There was also no shame in failing and having to try again – some American stars are in and out for years. But in Italy you’d be far more likely to enjoy a glass of wine at 11 o’clock in the morning than you would worry about whether that made you an alcoholic.

The Comedy Roast

seemed to go on forever and everyone had a drink in their hand all night long. Snoop was even smoking joints on the stage – which caused some controversy when it was reported the next day. I had a good evening though, sat there with my fizzy soft drink, but it opened my eyes to how many times I would have to face similar situations in everyday life. In those first few days I worried that I wouldn’t always be strong enough to say

‘No’. I resolved to check back into rehab the next weekend because I just didn’t feel ready to face the world.

That same week my agent told me VH1 were doing a reality show called

Celebrity Rehab

. I would be treated by Dr Drew Pinsky, a top specialist in substance abuse and even better, I would get paid for it. It was the perfect opportunity. I wasn’t in the slightest bit concerned about having my recovery filmed – I had lived so much of my life in front of the cameras by then. I had gotten drunk and acted like a fool on reality TV so I was certainly ready to set a better example for the viewers. There was opposition from those who felt that the whole idea behind Alcoholics Anonymous was that it was done in private, but I thought all of that was probably unnecessary. I passionately believed that you’ve got to show the world that it could happen to anyone, no matter who they are. Just as you might show the effects of war on television, you should show recovering addicts – you want to say, ‘This is what it fucking looks like’: you have to understand it.