You Must Remember This (7 page)

Read You Must Remember This Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

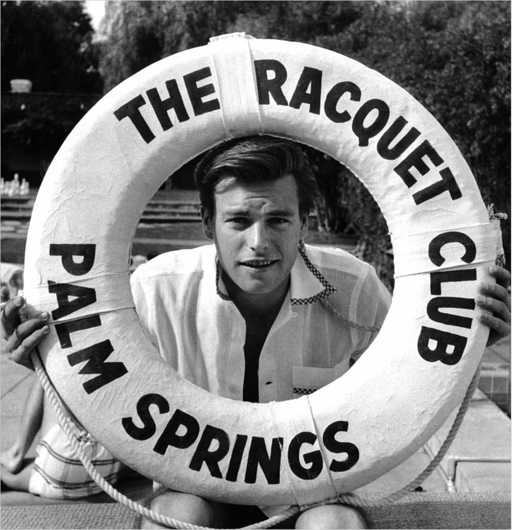

Here I am doing the publicity thing at Palm Springs Racquet Club.

Everett Collection

The attraction of Palm Springs was its hot, dry climate and complete seclusion, far from the studios and the gossip columnists. For years Palm Springs was one of the places you went if you were playing around on your spouse, or wanted to. The combination of a resort culture with geographical remoteness made for some wild times. As far as the people, it was the crème de la crème of the industry.

What was wonderful about Palm Springs was that it was an

entirely different environment than Los Angeles, and yet it was only two hours away. Palm Springs is surrounded by mountains—the San Bernardino Mountains to the north, the Santa Rosa Mountains to the south, the San Jacinto Mountains to the west, and the Little San Bernardino Mountains to the east. It’s situated in a valley, and gets unbelievably hot in the summer—a temperature of 106 is normal, and it can go even higher, then falling to anywhere from 77 to 90 degrees at night.

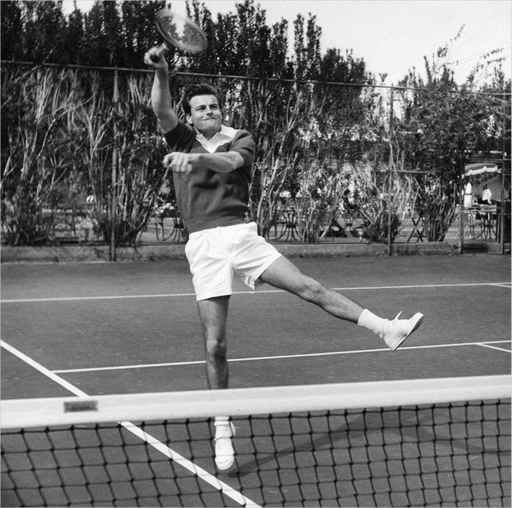

Playing in a singles match at Palm Springs Racquet Club.

Everett Collection

But that’s in the summer. In the winter, it’s idyllic; it rarely gets over 85 degrees or so, and the nights are cool.

The first time I went to Palm Springs was before World War II

with my father. I was immediately enchanted. We went riding in the desert, and tied our horses up at a place in Cathedral City where we bought delicious fresh orange juice.

Palm Springs then was the sort of town with no streetlights—after dark, the only illumination was the moon, but in the desert that’s much brighter than you think. I remember the mountains, the orange groves, the swimming pools, the desert sunsets, the air—so invigorating I always believed the oxygen content had to be higher than in the city.

Even then, the town had great bars. Don the Beachcomber’s had a beachhead there, as did the Doll House. And there was a restaurant called Ruby Dunes, which became one of Frank Sinatra’s favorite places.

Eventually, the unique environment of Palm Springs called for unique kinds of houses, and American modernist architects like Richard Neutra flourished there. Neutra’s Kaufmann House—built for the same man who’d commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater in Pennsylvania—was built in 1946.

Neutra stole at least one of my friend the great California architect Cliff May’s central ideas: the place is built around a courtyard and includes a fair amount of natural materials—the stone walls and chimney came from nearby quarries and match up with the colors of the adjacent San Jacinto Mountains. And Neutra went with an early version of xeriscaping, as he filled the front yard with large boulders and desert plants that didn’t need much water.

Neutra’s success in Palm Springs brought more commissions, and more modernist architects followed in his wake, although few of them had Neutra’s dominating personality. “I am not International Style,” he once said. “I am Neutra!” It wasn’t long before John Lautner, Albert Frey, and Rudolph Schindler were building there

as well. The result was that Palm Springs became a hotbed of modified Bauhaus aesthetics. But when I was first going there, most of the architecture was Mexican or Spanish villas.

In the ’60s, the houses were open in design, with air-conditioning—Palm Springs could never have been settled in a large way without the invention of air-conditioning—and windows that made the desert landscape part of the dwelling.

I remember the Palm Springs of my youth as something out of a western movie or, more specifically, a dude ranch. It was very western; hotel employees dressed up as if they were the Sons of the Pioneers, in embroidered shirts and cowboy boots. The bartender at the Racquet Club was actually named Tex. Tex, the lawyer Greg Bautzer, and I once got into a big fight at the Racquet Club with a couple of obnoxious out-of-town drunks. Tex could not only mix a killer martini, he could also clean out a room, and quickly.

The important thing to note about Palm Springs is that it was actually a small town, an intimate place whose population was mostly an extension of Hollywood.

There was, for instance, Alan Ladd Hardware, which I suspect had been started by Ladd or his wife Sue Carol as a hedge against the vagaries of the movie business. It was actually a spectacularly well-stocked and successful store, and it was there for a long, long time. And I still remember Desmond’s department store.

Among the other celebrities who lived in Palm Springs were Zane Grey, Sam Goldwyn, the composer Frederick Loewe, Dinah Shore, and Frank Sinatra. William Powell and his much younger wife Diana Lewis—everybody called her “Mousie”—had moved there after he retired, and I got to know him well.

As you might expect, Bill Powell was a gentleman. He was a good drinking man, and surprisingly self-effacing. One time I complimented him on the marvelous series of movies he had made with Myrna Loy and the qualities he had brought to all of his films, but he didn’t seem to think they, or he, were all that much.

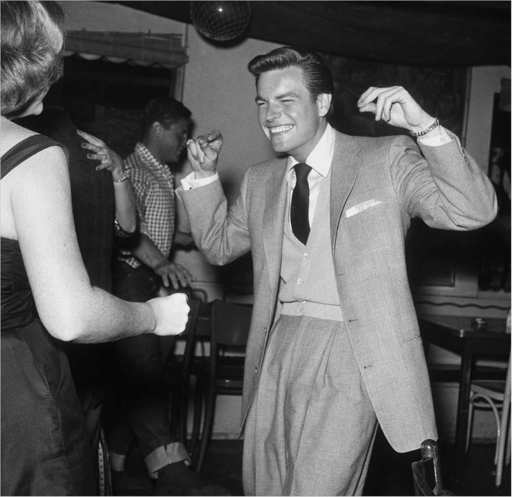

Yours truly having a good time at a party in Palm Springs, circa 1955.

Everett Collection

“I never really did anything different,” he said, referring to his career. I thought he was being unfair to himself, and still do.

In the 1950s, Palm Springs began to change. When I first went there with my father, it had precisely one golf course: the O’Donnell, a little nine-holer. But soon other courses sprang up—Thunderbird, Tamarisk—and later the Eisenhower Medical Center changed the nature of the town. It became far more of a retirement community than it ever had been, and the geriatric influence shifted the nature

of the town—it became less exuberant, more sedate. At the same time, it also became less seasonal and more of a year-round place.

Frank Sinatra started out by buying a little three-bedroom tract house near the Tamarisk Country Club and began remodeling and adding on until he had a very large compound with guesthouses, a helicopter pad, and a caboose that held his huge model train layout—Frank loved his Lionel trains. Next door to his own compound, he built a house for his mother, Dolly. Down the street Walter Annenberg had a private golf course.

For years, we would go to Frank’s for New Year’s Eve. Dean Martin would be there, as would Sammy Davis Jr., perhaps Angie Dickinson. Frank appreciated the remoteness of Palm Springs but also liked the fact that the place wasn’t so remote he’d be deprived of the amenities he wanted. By the time he was finished with the house, it had a walk-in freezer and a huge dining room that sat twenty-four people. The interior decoration made some of the place look like a luxurious modern hotel, but I always figured that was because Frank had spent so much of his life in hotels that it was the kind of environment in which he felt comfortable.

Eventually I moved to Palm Springs, too, when I married my second wife, Marion, in the early 1960s, and my kids went to school there. We lived there for seven years—seven very happy years. My house was built out of desert rock and was Spanish in design—Herman Wouk lives there now. That house was just a bit away from the house that had been built by Zane Grey, and it was right across the street from one of King Gillette’s houses.

My proximity to Zane Grey’s house was thrilling to me. I’d read his novels as a boy, and knew he’d been a great outdoorsman who had done a great deal to popularize deep-sea fishing. It always

delighted me to think how we could have been neighbors if Grey hadn’t gone and died.

My future wife, Jill, and Frank at the very first Frank Sinatra Golf Tournament in Palm Springs, circa 1960.

Lester Nehamkin/mptimages.com

When Natalie and I married for the second time, in 1972, I still had the house, and we decided to settle there. We added some rooms on, and when our daughter, Courtney, was born, we raised her there. Then we bought our house in Beverly Hills from Patti Page.

There were other places where people went to get away, some of them pretty far afield. Gamblers often went over the border to Tijuana, Agua Caliente, and Ensenada. It’s an open question who was the biggest gambler in Hollywood, the answer known only to accountants of the period. I’d put my money on either David O.

Selznick or Joe Schenck, the latter of whom actually had a casino in his house, although when the police closed it down Joe claimed he didn’t know about it.

Uh-huh.

Then there was Harry Cohn, founder of Columbia Pictures. Cohn’s annual one-month vacation took place at Saratoga Race Course, and he is said to have averaged five thousand to ten thousand dollars a day in bets. This went on until he hit a cold streak and lost four hundred thousand dollars.

A normal man might have had a nervous breakdown over losing that amount of money—I know I would. In fact, Cohn’s brother, a cofounder of the studio, had to warn him that he would be removed from the presidency of Columbia Pictures if he didn’t get his gambling under control.

So Harry Cohn slowly put aside horses in favor of betting on football, and cut back to betting only about fifty dollars on college games.

It makes perfect sense that many of the moguls were, in fact, serious gamblers, because spending millions of dollars on a movie is nothing if not a gamble. B. P. Schulberg, who ran Paramount in the early 1930s, was a particularly degenerate gambler, and it ruined his career. There were quiet poker games around town as well, and people like Eddie Mannix, Joe Schenck, Sid Grauman, Norman Krasna, and the Selznick brothers were regular participants. A lot of money changed hands on these outings; the story goes that B. P. Schulberg once dropped a hundred thousand dollars in one night—and this at a time when a hundred thousand dollars was serious money, even in Hollywood. The Selznicks came by their habit naturally; their father had ruined his business by gambling.