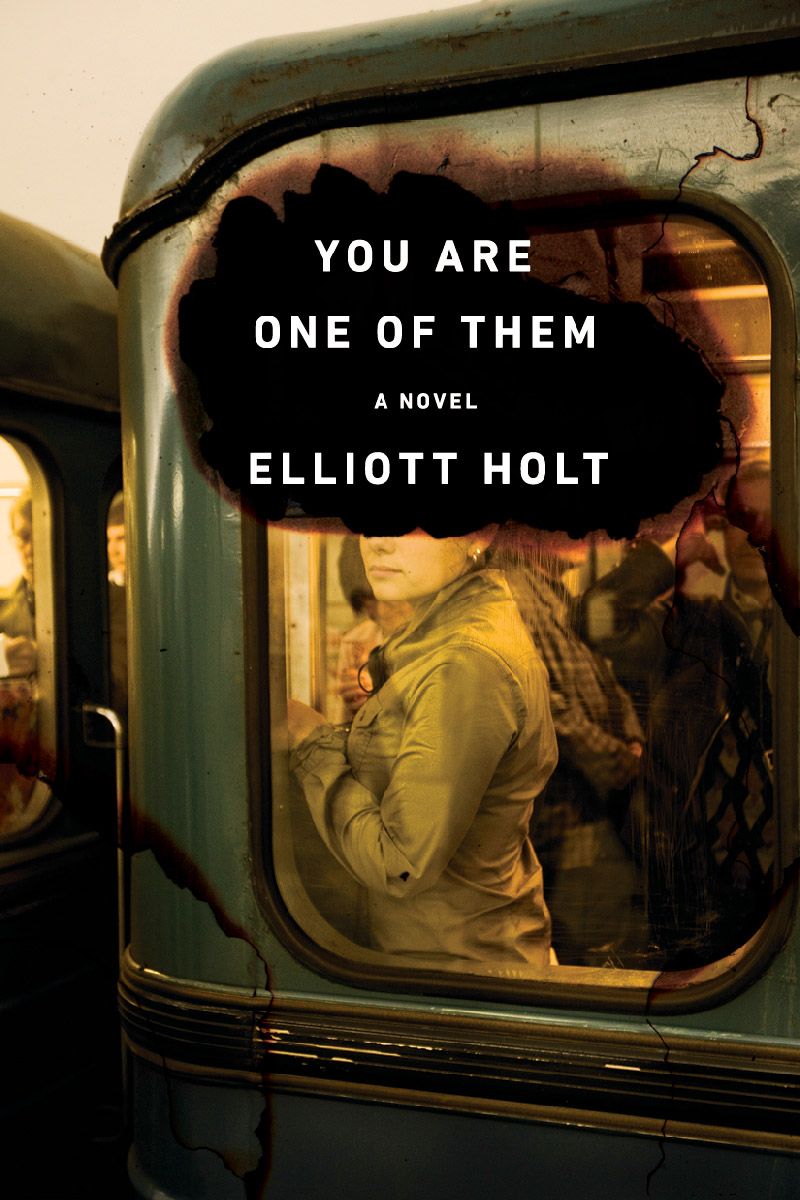

You Are One of Them

Read You Are One of Them Online

Authors: Elliott Holt

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA

•

Canada

•

UK

•

Ireland

•

Australia

•

New Zealand

•

India

•

South Africa

•

China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

Copyright © Elliott Holt, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint excerpts from the following copyrighted works:

Endgame by Samuel Beckett. English translation copyright © 1957 by the Estate of Samuel Beckett. Used by permission of Grove/Atlantic, Inc. Any third party use of this material, outside of this publication, is prohibited.

Eloise in Moscow by Kay Thompson. Copyright © 1959 Kay Thompson, copyright renewed 1987 Kay Thompson. Reprinted with permission of Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division.

ISBN 978-1-101-61797-7

This is a work of fiction. Apart from the well-known actual people, events, and locales that figure in the narrative, all names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to current events or locales, or to living persons, is entirely coincidental.

For my mother,

who wasn’t afraid of anything

Then babble, babble, words, like the solitary child who turns himself into children, two, three, so as to be together, and whispering together, in the dark.

—Samuel Beckett

, Endgame

I

N MOSCOW

I was always cold. I suppose that’s what Russia is known for. Winter. But it is winter to a degree I could not have imagined before I moved there. Winter not of the pristine, romantic

Doctor Zhivago

variety but a season so insistent and hateful that all hope freezes with your toes. The snow is cleared away too quickly to soften the city, so the streets are slushy with resentment. And I felt like the other young women trudging through that slush: sullen and tired, with a bluish tint to the skin below the eyes that suggests insomnia or malnutrition or a hangover. Or all of the above. Every day brought news of a drunk who froze to death. I saw one: slumped over on a bench on Tverskoy Boulevard with a bottle between his legs and icicles decorating his fingers. Distilled into something so pure and solid that I didn’t recognize it as death until I got up close. The babushka next to me summoned the police.

I cracked under the weight of the cold. My only recourse was to eat. I inhaled entire packages of English tea biscuits in one sitting. They came stacked in a tube, and when I found myself halfway through one, I decided I might as well finish it. I polished off a whole tube every night after work and then pinched the extra flesh around my hips in the bathtub and thought,

At least I’m warm.

It was 1996. At the English-language newspaper where I worked, the other expats were always joking. Russia, with all its quirks, was funny. There was a sign at Sheremetyevo Airport, perched at the entrance to the short-term-parking lot, which had been translated into English as

ACUTE CARE PARKING

. It was a sign better suited to a hospital, where everything is dire. And at the smaller airports, the ones for regional flights, the Russian word for “exit,”

vykhod,

was translated into English as

GET OUT

. A ticket to Sochi, for example, said you would be departing from Get Out #4. I laughed with them, but I knew that eventually these mistranslations would be corrected, that Russia would grow out of its awkward teenage capitalism and become smooth and nonchalant. You could see the growing pains in the pomaded hair of the nightclub bouncers, in the tinted windows of the Mercedes sedans on Tverskaya, in the garish sequins on the Versace mannequins posing in a shop around the corner from the Bolshoi Theater.

At the infamous Hungry Duck, I watched intoxicated Russian girls strip on top of the bar and then tumble into the greedy arms of American businessmen. American men still had cachet then; as an American woman, I hugged the sidelines. (“Sarah,” said the Russian men at my office, “why you don’t wear the skirts? Are you the feminist?” They always laughed, and it was a deep, carnivorous sound that made me feel daintier than I am.) Everyone in Moscow was ravenous, and the potential for anarchy—I could feel its kaleidoscope effect—made a lot of foreigners giddy. Most of the reporters at my paper spoke some Russian. But among the copy editors, many of whom were fresh out of Russian-studies programs and itching to put their years in the language lab to good use, the hierarchy was built on who spoke Russian best. They were not gunning for careers in journalism; they just wanted to be in the new post-Soviet Moscow—the wild, wild East—and this job paid the bills. The Americans with Russian girlfriends—“pillow dictionaries,” they called them, aware that these lanky, mysterious women were far better-looking than anyone they’d touched back home—began to sound like natives. They were peacocks, preening with slang. In the office each morning, they’d pull off their boots and slide their feet into their

tapochki

and head to the kitchen for instant coffee—Nescafé was our only option then—and they’d never mention their past lives in Wisconsin or Nevada or wherever they escaped from.

“Oy,”

they said, and

“Bozhe moy,”

which means “my God” but has anguish in Russian that just doesn’t translate. A little bravado goes a long way toward hiding the loneliness. You can reinvent yourself with a different alphabet.

On Saturdays at the giant Izmailovo Market, tourists haggled for Oriental rugs and

matryoshka

dolls painted to resemble Soviet leaders—Lenin fits into Stalin, who fits into Khrushchev, who fits into Brezhnev, who fits into Andropov, who fits into Gorbachev, who fits into Yeltsin. History reduced to kitsch. While shopping for Christmas gifts once, I stopped by a booth where a spindly drunk was selling old Soviet stamps. And there, pinned like a butterfly to a tattered red velvet display cushion, was Jenny. Her image barely warped by time.

“Skolko?”

I said. The man asked too much. He had the deadened eyes of a person who hasn’t been sober for years, and I didn’t feel like bargaining, so I handed him the money. He could smell my desperation. He put the stamp in a Ziploc bag, and on the way back home on the Metro I studied her through the plastic. My best friend, commemorated like a cosmonaut. Her name had been transliterated into Cyrillic: it said above the smiling photo of her freckled face. A five-kopeck stamp from the postal service of the USSR. I had just paid ten dollars for something that was originally worth next to nothing.

it said above the smiling photo of her freckled face. A five-kopeck stamp from the postal service of the USSR. I had just paid ten dollars for something that was originally worth next to nothing.

Conspiracy theorists will tell you that Jennifer Jones’s death was not an accident. They will tell you that her plane crashed not because of mechanical failure, not because the pilot was suffering from dizzy spells, but because the CIA shot it down. She had become a Soviet pawn they say, too sympathetic to the party. Others say that the KGB was responsible, that after the press took pictures of her smiling at the Kremlin and quoted her saying how nice the Russians were, they needed to quit while they were ahead. I’ve read the official reports. I heard the pundits spew their Sunday-morning-talk-show ire. But I don’t recognize the Jennifer Jones I knew in their versions of the story.

Some people will tell you that all of it was propaganda, that she was just a pawn in someone else’s game, but the letter—the original letter—was real. It came from a real place of fear. The threat used to be so tangible. I was prepared to lose the people I loved best. My mother, with her fuzzy hair and lemon-colored corduroys; our dog, Pip; and Jenny. Always Jenny, whose last act must have been storing her tray table in its upright and locked position. Yuri Andropov wished her the best in her young life. Maybe this blessing was a curse.

Or maybe her luck just ran out.