Yes Please (22 page)

Authors: Amy Poehler

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #Humor, #Form, #Essays, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #General, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video

EILEEN FRANCES MILMORE WAS BORN FEBRUARY 7, 1947, IN WATERTOWN, MASSACHUSETTS.

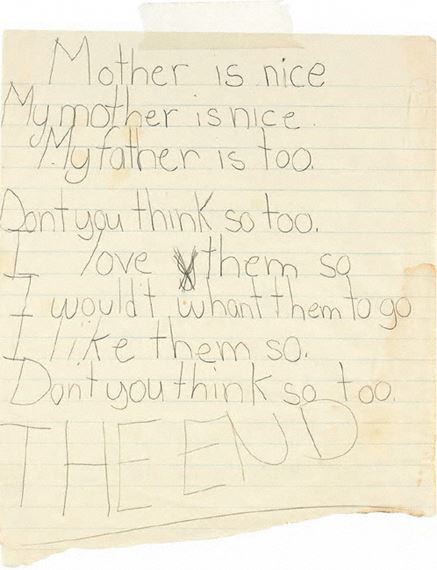

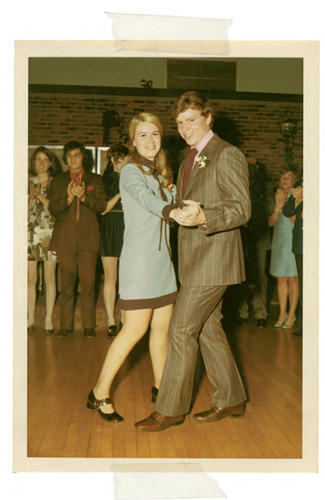

She was the oldest of three children. Her mother, Helen, worked as a secretary at St. Patrick’s High School and her father, Stephen, was a firefighter and World War II veteran. She went to Boston State College and was an excellent student. She met my dad on a school bus on the way to a basketball game. She was head cheerleader and he was the best player on the team. She tapped him on the head and asked to sit with him. She was twenty-three when she got married, twenty-four when I was born, and forty-one when she got her master’s degree in special education. She taught for thirty-one years, starting in elementary and ending in high school special ed. One of her most exciting moments was sharing an elevator with Sally Field. During a recent trip to Amsterdam, she sent me a picture of her smoking marijuana for the first time just because I asked her to. She is kind, she is chatty, and she writes beautiful poetry.

WILLIAM GRINSTEAD POEHLER WAS BORN SEPTEMBER 21, 1946, IN WAYNESBORO, VIRGINIA.

His mother, Anna, was first married to William, his father, who left right after he was born. For the first five years of his life, my father lived in a foster home. Anna remarried and her new husband, Carl Poehler, adopted my father and his sister and moved them all to Massachusetts. Anna and Carl had two more sons. The first day my father met my mother he came home and told my grandmother, “I have met the girl I am going to marry.” He was an elementary school teacher and also a financial planner. One of his most exciting moments was sharing an elevator with Boston Celtics Robert Parish and Kevin McHale. For my wedding, my father, his friends, and my uncles performed a surprise tap-dance number with top hats and canes. He is generous, nosy, and good at arm wrestling.

They have been married almost forty-five years. Here are some things they have taught me.

MOM

• Make sure he’s grateful to be with you.

• Your boobs won’t be as big as mine but you will be happy about that as you get older.

• Always tell people when they do a good job.

• Always have a messy purse.

• Guilt works.

• You are the smartest and best.

•

Monty Python

is funny.

• Be nice to your brother.

• Be a light sleeper, and every time your kid wakes you up, scream like you are being attacked.

• Have fun dancing.

• Have male friends.

• Have more female friends.

• Your female friends will outlast every man in your life.

• Love your husband and don’t belittle him.

• Love your kids and hope they do better than you did.

• You don’t want to be the sexy mom.

• Dye your hair constantly.

• There’s not much we can do about our Irish eyebrows.

• Postpartum depression, anxiety, and skin cancer run in our family.

• Ask your kids how they are doing but sometimes ignore them when they say, “Not great.”

• Love your work.

• Study hard and know how to write and read well.

• Memorize poems.

•

Be nice to teachers. Teachers don’t like kids who don’t like teachers.

• Always bring wine.

• A home-cooked meal isn’t so important.

• TV in your bedroom is okay.

• Follow sports and leave the room if you’re a jinx.

• Be careful.

DAD

• Ask for what you want.

• Know how to shoot a free throw and field a ground ball.

• There are ways around things that aren’t always legal.

• Hide cash in your house.

• Always overtip but make a big deal out of paying the check.

• Eat whatever you want.

• Keep trying.

• Never remember anyone’s name.

• Girls can do anything boys can do.

• Street smarts are as important as book smarts.

• “Your mother is smarter than me and I am fine with it.”

• Don’t work too hard.

• You can have a chaotic childhood and still provide a stable home.

• Ask everyone how much money they make.

• Keep the TV loud and all the lights on in the house.

• You don’t want to be the creepy dad.

• It’s okay to cry.

• It’s okay to argue.

• Tell everyone you meet what your daughter does until your daughter asks you to stop.

• Our family has a history of bad stomachs, heart problems, and a loss of hearing we will deny.

• Don’t hit your kids, except that one time.

• Love your wife’s family.

• Don’t listen to experts.

• Everything in moderation.

don’t forget to tip your waitresses

T

HE TOWN WHERE I GREW UP WAS DECIDEDLY BLUE-COLLAR, FILLED WITH TEACHERS AND NURSES AND THE OCCASIONAL SALES MANAGER

.

My friends and I fell asleep to the sound of our parents arguing about car payments and tuition. It was our soundtrack, this din of worry. If you were old enough, you were expected to have a part-time job.

When I was sixteen, I got one. I was a junior secretary in a podiatrist’s office near my house in Burlington. I had to wear a short white skirt, a tight blouse, and high-heeled shoes. This outfit made me look like a teenage nurse, which sounds hot but I promise you was not. I was a teenager during a period of truly awful style. It made sense that my friends and I all had part-time jobs, because we dressed like Melanie Griffith in

Working Girl

during a long subway commute. Hair spray was king, and the eighties silhouette in Burlington was big hair, giant shoulder pads, chunky earrings, thick belts, and form-fitting stretch pants. My silhouette was an upside-down triangle. Add in my round potato face and hearty eyebrows and you’ve got yourself a grade-A boner killer, so remember that before you try to jerk it to my teenage-nurse story.

Anyway, this other nurse and I used to jump around in our underwear and kiss each other for fun.

Oh wait, what I meant to say was that I answered phones and filed things. The best part of my job was leaning into the waiting room and whispering, “The doctor will see you now.” It always felt like such a WASPy phrase. Right up there with “It truly is my pleasure” and “We just got back from the country.” Every once in a while we would get an exciting sprained ankle or a flat-feet emergency, but usually the patients were just old people who couldn’t cut their own toenails anymore.

I was a really good waitress. Waitressing takes a certain gusto. You need a good memory and an ability to connect with people fast. You have to learn how to treat the kitchen as well as you treat the customers. You have to figure out which crazy people to listen to and which crazy people to ignore. I loved waiting tables because when you cashed out at the end of the night your job was truly over. You wiped down your section and paid out your busboy and you knew your work was done. I didn’t take my job home with me, except for the occasional nightmare where I would wake up in a cold sweat and remember I never brought table 14 their Diet Coke.

My first waitressing job was in the summer of 1989, a few months before I left for college. I was seventeen and sticky. I earned the extra money I needed for textbooks scooping ice cream at Chadwick’s, a local parlor that specialized in sundaes and giant steak fries. Chadwick’s was in Lexington, Massachusetts, the rich town next door (the Eagleton to our Pawnee). Lexington was the famous home of the “Shot Heard ’Round the World.” Burlington was the home of the mall. Lexington, as it turns out, is also Rachel Dratch’s hometown, and much later I would learn that she also worked at the same sticky emporium a few years before I did. Imagine if our paths had crossed! Imagine how hilarious we would have been while we shoved toothpicks in the club sandwiches! Think of all the jokes about “marrying the ketchups.” Such a waste. Lexington High still plays Burlington High on Thanksgiving Day, and Dratch and I trash-text each other. She calls me Burlington garbage and I tell her to go drive her Mercedes into a lake. In my town, the best way to insult someone was to call them rich and smart, which, looking back, was maybe a little shortsighted of us.

You know what? Who cares. Burlington rules! GO RED DEVILS!!

Summer jobs are often romantic; the time frame creates a perfect parentheses. Chadwick’s was not. Hard and physical, the job consisted of stacking and wiping and scooping and lifting. At the end of my shift, every removable piece of the restaurant would be carted off and washed. Vinyl booths were searched and scrubbed. This routine seemed Sisyphean at first, but I soon learned the satisfaction of working at a place that truly closed. I took great joy in watching people stroll in after hours, thinking they could grab a late-night sundae. I would point to the dimmed lights and stacked chairs as proof that we were shut. It was deliciously obvious and final.

Chadwick’s was one of those fake old-timey restaurants. The menus were written in swoopy cursive. The staff wore Styrofoam boaters and ruffled white shirts with bow ties. Jangly music blared from a player piano as children climbed on counters. If the style of the restaurant was old-fashioned, the parenting that went on there was distinctly modern. Moms and dads would patiently recite every item on the menu to their squirming five-year-olds, as if the many flavors of ice cream represented all the unique ways they were loved.