World War One: History in an Hour (8 page)

Read World War One: History in an Hour Online

Authors: Rupert Colley

Tags: #History, #Romance, #Classics, #War, #Historical

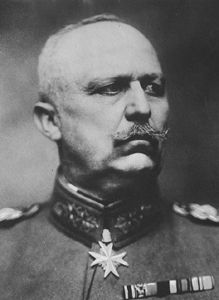

In August 1916, Hindenburg and Ludendorff replaced Falkenhayn. With the Kaiser increasingly sidelined, the duo ran a virtual military regime. Hindenburg implemented Germany’s policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, dictated the harsh terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litoski and helped Ludendorff launch the Spring Offensive of 1918.

A monarchist at heart, Hindenburg found it personally very difficult forcing the Kaiser to abdicate – but the removal of Wilhelm II was Germany’s price for peace. Retiring for a second time in 1919, Hindenburg was again prised back when he was persuaded to accept the presidency of the Weimar Republic – following Ebert’s, the Republic’s inaugural president, death in 1925. In July 1932, still convinced that Germany would be better served with a monarch, and still wanting to retire, Hindenburg was again persuaded to stand for re-election as the only alternative to the rising popularity of the Nazi party. Hindenburg narrowly won the election but a second election, in November 1932, forced Hindenburg into forming a coalition government with Adolf Hitler as his Chancellor.

Following the Reichstag fire in February 1933, Hitler manipulated Hindenburg into suspending the constitution. Hindenburg, increasingly senile, died in 1934. He was buried at Tanneburg, the scene of his greatest triumph, until 1946, when his body was re-interred in the town of Marburg.

Erich Ludendorff 1865–1937

Ludendorff made his reputation early in the war with the capture of the Belgium fortress city, Liège, and, alongside Hindenburg, his successes on the Eastern Front. Following Falkenhayn’s dismissal in August 1916, Ludendorff had increasing influence on how Germany was run, both militarily and domestically, gearing the whole German economy up for war. Ludendorff gave his permission for Lenin to return to Russia through Germany, believing, correctly, that Lenin’s presence in Petrograd would derail Russia’s war effort.

Erich Ludendorff

George Grantham Bain collection, Library of Congress

With Russia out of the war, Ludendorff spearheaded Germany’s Spring Offensive of 1918, determined to strike before the arrival of American troops. His initial successes were pushed back by the Allies’ counter-attack, forcing Ludendorff to canvas US president, Woodrow Wilson, for a mediated peace. On the day of the Armistice, Ludendorff escaped to Sweden, disguised with spectacles and a false beard.

Ludendorff was instrumental in peddling the ‘stab in the back’ myth, blaming the politicians for Germany’s defeat. Vehemently opposed to the Weimar Republic, Ludendorff took part in the failed Kapp

putsch

of 1920, and Hitler’s Munich

putsch

three years later. Tried for his role in Munich, Ludendorff was acquitted.

In 1924, Ludendorff took a seat in the Reichstag representing the Nazi party. In 1925, he stood for president against his old ally, Hindenburg, but fared poorly. Keeping his seat in the Reichstag but increasingly senile and disapproving of Hitler, he became an embarrassment to the Nazis, and in 1928 obligingly retired.

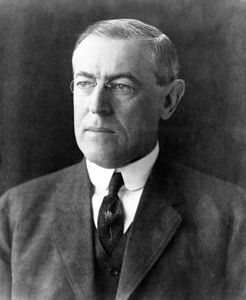

Woodrow Wilson 1856–1924

Born in Virginia to a slave-owning Presbyterian minister, Woodrow Wilson became the first Southern US president since Andrew Johnson in 1869. He was elected the twenty-eighth US president in 1911, Wilson, a Democrat, was determined to maintain American neutrality during the war. He was re-elected in 1916 with the slogan ‘He kept us out of the war’. Germany’s policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, which cost American lives, together with the exposure of the Zimmermann Telegram, forced the President’s hand. In April 1917, he sought Congress’ mandate to declare war on Germany, a course necessary to make the ‘world safer for democracy’.

Woodrow Wilson, 1912

Library of Congress

In January 1918, Wilson, in another address to Congress, introduced his Fourteen Points, a blueprint for a post-war peace that would avoid overly punitive terms on a vanquished Germany and her allies. The establishment of a body to act as an international arbitrator, the League of Nations, was also core to Wilson’s philosophy.

By the time the Paris Peace Conference finished in January 1920, not much of the Fourteen Points remained and the terms imposed on Germany in the Treaty of Versailles were indeed punitive. The League of Nations however did become a reality, its inaugural assembly taking place on the last day of the conference. However, there was no representation from the US.

Despite receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919, Wilson returned to America to find much opposition to the treaty both from isolationists and Republicans. While touring the nation, trying to garner support, Wilson suffered the first of several strokes. Paralyzed on his left side and blind in one eye, Wilson effectively retired from his duties but remained in office until the election of November 1920.

Wilson’s successor in the White House, Republican Warren Harding, neither allowed the US to join the League of Nations or to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. Wilson died on 3 February 1924, aged sixty-seven.

Edith Cavell 1865–1915

When the Great War broke out, Edith Cavell had been working as a matron in a Brussels nursing school since 1907. Following the German occupation of the city, Cavell hid refugee British soldiers and provided over 200 of them the means to escape into neutral Netherlands. Arrested on 3 August 1915, Cavell readily admitted her guilt.

Her case became a

cause célèbre

. The British government, realizing the Germans were acting within their own legality, was unable to intervene. However, the US, as neutrals, pointed to Cavell’s nursing credentials and her saving of the lives of German soldiers, as well as British, but to no avail. The nurse was found guilty and sentenced to be shot.

Edith Cavell

On the evening before her execution, Cavell was visited by an army chaplain. She told him, ‘Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.’ The words are inscribed on Cavell’s statue, near Trafalgar Square in London.

On 12 October 1915, facing the firing squad, Cavell said, ‘My soul, as I believe, is safe, and I am glad to die for my country’. The British made propaganda capital out of the nurse’s execution, stoking up anti-German feeling by exploiting the idea of a gentle nurse slaughtered by the German barbarian. The German foreign secretary, Alfred Zimmermann, expressed pity for Cavell but added that she had been ‘judged justly’.

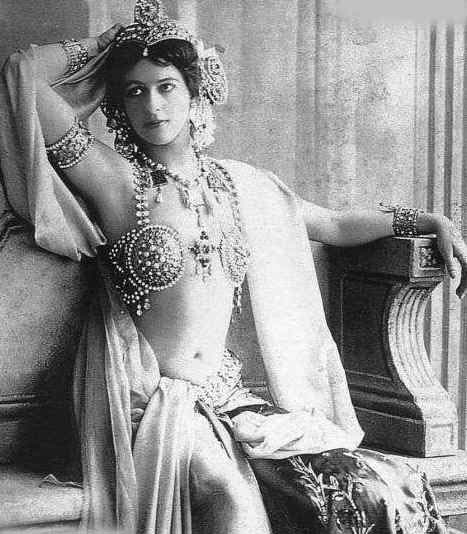

Mata Hari 1876–1917

Born to a wealthy Dutch family, Gertrud Margarete Zelle responded to a newspaper advertisement from a Rudolf MacLeod, a Dutch army officer of Scottish descent, seeking a wife. The pair married in 1895 and moved to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) where they had two children. Their son died aged two from syphilis, most likely caught from his father – their daughter would die a similar death, aged twenty-one. Twenty years older, MacLeod was an abusive husband and in 1902, on their return to the Netherlands, they separated.

Mata Hari

Zelle moved to Paris, where she started to earn a living by modelling and dancing, changing her name to Mata Hari. Exotically dressed, she became a huge success and was feted by the powerful and rich of Paris, taking on a number of influential lovers. She travelled numerous times between France and the Netherlands. Her movements and liaisons however caused suspicion.

Arrested by the British, Hari was interrogated. She admitted to passing German information on to the French. In turn, the French discovered evidence, albeit of doubtful authenticity, that she was spying for the Germans. Returning to Paris, Hari was then arrested by the French and accused of being a double agent. The evidence against her was insubstantial, but she was nevertheless found guilty and executed, aged forty-one on 15 October 1917.

The Unknown Warrior

The vicar of Margate in Kent, the Reverend David Railton, was stationed as a Padre on the Western Front when he noticed a temporary grave with the inscription, ‘An Unknown British Soldier’. Moved by this simple epitaph, he suggested an idea to the Dean of Westminster, who passed it onto Buckingham Palace. The idea of a tomb of the Unknown Soldier was well received and given the go ahead.

The Unknown Warrior, Westminster Abbey

On 9 November 1920, the remains of six unidentified British soldiers were exhumed – one each from six different battlefields (Aisne, Arras, Cambrai, Marne, Somme, and Ypres). The six corpses were transported to a chapel near Ypres, where they were each covered by the Union flag. There, in the company of a Padre (not Reverend Railton), a blindfolded officer entered the chapel and touched one of the bodies.

Placed in a coffin, the chosen soldier was taken back to England via Boulogne, and from there across the Channel on board the HMS

Verdun

(named after the French battle). A train transported it to London. All along the way, the body was afforded pomp and ceremony – processions, gun salutes and, at Boulogne, a salute from Marshal Foch.