World War One: History in an Hour (4 page)

Read World War One: History in an Hour Online

Authors: Rupert Colley

Tags: #History, #Romance, #Classics, #War, #Historical

By 1916, the trench system had become a fixed and elaborate aspect of the war in the west. Front-line trenches were backed by reserve and support lines and consisted of underground bunkers. Life in the trenches became a routine of filth, lice, rats, cold, deprivation, and boredom punctuated with moments of terror. Weeks of living in mud often resulted in trench foot. The German, content to secure their defensive positions, built more sophisticated trenches that were deeper, more secure, warmer and, in some instances, boasted electricity. For the Allies, determined to rid the German foe from French or Belgium soil, the trenches were only ever meant to be a temporary improvisation.

British soldier during the Battle of the Somme, July 1916

IWM Collections, Q 3990

The system always favoured defence as was shown time and again throughout the war. Generals, planning their advances, continued to advocate the use of preliminary artillery to pound the enemy’s trenches and flatten its barbed wire. Then, having pulverized the enemy’s front line, infantry could advance across the expanse of No Man’s Land, typically between 100 and 400 metres wide, and engage the enemy, finishing him off by bayonet.

The reality always proved otherwise. The artillery, however sustained, rarely did more than limited damage either to trench or manpower. Men, on the receiving end of artillery, would simply disappear underground into the concreted bunkers only to re-emerge as the infantry approached, and mow them down with machine-gun fire. The gains, if any, were usually minimal, soon reversed and came at a high cost.

The cost on the minds and shattered nerves of the men was also high. Combat stress, or ‘shellshock’, became a common occurrence. Sympathy for these non-visible wounds was not always forthcoming, especially during the early stages of the war. 80,000 British servicemen – 2 per cent of those who saw active service – suffered from forms of shellshock. Men, were so traumatized, they would forget their own names. For many, unable to cope, running away seemed the only option. The risk was high – the French executed over 600 men for desertion or cowardice, the British and Commonwealth 306, and Germany 18. The US sentenced 24 to death but no executions were carried out.

Wounded British soldiers, Battle of the Somme, July 1916

IWM Collections, Q800

The Battle of the Somme started with the usual preliminary bombardment. Lasting five days, and involving 1,350 guns, soldiers were assured that the eighteen-mile German front line would be flattened – it would just be a matter of strolling across and taking possession of the German trenches – beyond that, lay Berlin.

The British army at the Somme consisted mainly of Kitchener recruits, who had received only minimal training, and were to cross No Man’s Land lumbered with almost 70 lbs of equipment. The advance started at 7.30 a.m. on 1 July 1916. To the right of the British, a smaller French force, transferred from Verdun. The men advanced in rigid lines. The German trenches ahead had not been decimated by the artillery but were brimming with guns pointing towards the advance. What followed went down as the worse day in British military history – 57,000 men fell on that first day alone, 19,240 of them lay dead.

One of Britain’s generals at the Somme, Sir Beauvoir de Lisle, wrote, ‘It was a remarkable display of training and discipline, and the attack failed only because dead men cannot move on’. Despite the appalling losses, Haig decided to ‘press [the enemy] hard with the least possible delay’. Thus the attack was resumed the following day – and the day after that.

On 15 September, Haig introduced the modern equivalent of the cavalry onto the battlefield – the tank. Originated in Britain, and championed by Churchill, the term ‘tank’ was at first merely a codename to conceal its proper name of ‘landship’. Despite advice to wait for more testing, Haig had insisted on their use at the Somme. He got his way and the introduction of thirty-two tanks met with mixed results. Many broke down, but a few managed to penetrate German lines. As always, the Germans soon plugged the hole forged by the tanks. Nonetheless, Haig was impressed and immediately ordered a thousand more.

The Battle of the Somme ground on for another two months. Soldiers from every part of the Empire were thrown into the mêlée – Australian, Canadian, New Zealanders, Indian and South African all took their part. The battle finally terminated on 18 November, after 140 days of fighting. Approximately 400,000 British lives were lost, 200,000 French, and 400,000 German. For this the Allies gained five miles. The Germans, having been pushed back, merely bolstered the already heavily fortified second line, the Hindenburg Line.

In Germany, pressure was mounting. A British blockade of German ports was having an effect – resulting in desperate food shortages, food strikes and what the Germans called the ‘turnip winter’ of 1916–17. The scale of losses at the Somme brought about the sacking of Falkenhayn in August 1916, replaced by the duo that had so much success on the Eastern Front – Hindenburg and Ludendorff.

Falkenhayn was not the only casualty – in December 1916 in France, Joffre was replaced by the popular Robert Nivelle who had made his reputation as Pétain’s deputy during Verdun. Nivelle promised he had a scheme which would win the Allies the war within just two days. When Nivelle revealed his plan, it seemed to both the French and British no different from previous strategies. Nivelle threatened to resign. The government, fearing the backlash of the French public, allowed Nivelle free rein.

Changes were afoot in Britain also – Herbert Asquith, too long an impotent leader of a coalition, resigned, to be replaced on 7 December 1916 by former Secretary of State for War, David Lloyd George. Before the war, Lloyd George had been amongst its staunchest opponents and almost resigned on the issue. Asquith persuaded him otherwise but it earned Lloyd George much rancour from within his own party, the Liberals, so that as a coalition prime minister he became overly dependent on the Conservative majority. As the new prime minister, Lloyd George was committed to winning the war, ‘The fight must be to the finish – to a knockout blow’ but he would have to work with his commander-in-chief, Haig, whom he disliked and felt had little regard for the lives of his men. When, in February 1917, Lloyd George effectively subjugated Haig and his generals to the French, albeit only for the duration of the Nivelle’s offensive, he also earned the animosity of Haig.

Part of Nivelle’s grand plan was to distract the Germans with an offensive designed to relieve the stricken city of Arras, in Belgium. The Germans had deeply entrenched themselves in the high ground of Vimy Ridge surrounding the city back in September 1914, and had pounded the city ever since. Previous attempts to dislodge the Germans had failed. Opening on 9 April 1917, a force of British, ANZACs and Canadians managed to regain the ridge. Despite the successes at Vimy Ridge, elsewhere the Germans counter-attacked and the familiar pattern reasserted itself.

A week later, on 16 April, Nivelle launched his main offensive on which he had staked his reputation. The Second Battle of the Aisne was doomed for failure from the start. Nivelle’s carefully laid plans had fallen into German hands who prepared accordingly. The introduction of French tanks had no effect, and French artillery fell on their own infantry. The losses were huge. Nivelle’s promise of a forty-eight hour victory evaporated as the battle continued on for two weeks and petered out in early May. Nivelle, briefly the would-be saviour of France, was sacked and replaced by his former boss, Philippe Pétain, a man who was unusually sympathetic to the plight of his men. It was just as well because within the army were the first murmurs of dissent.

From dissent came mutiny. In May 1917, French soldiers refused to fight anymore. The word spread and thousands deserted. Fortunately for Pétain, his front-line troops remained in place. Behind the lines, men, worn down by war, filthy conditions, and the lack of sufficient medical care, refused to obey orders or return to the front. Painstakingly, Pétain managed to restore order through a combination of the carrot and stick. Ringleaders were arrested, court-marshalled and, in forty-three cases, executed. In the longer term, Pétain doubled a soldier’s length of leave, improved conditions, food and welfare. Most importantly, Pétain promised the French soldier that there would be no more pointless offensives or risks taken, until both the Americans had arrived and tanks were in full supply.

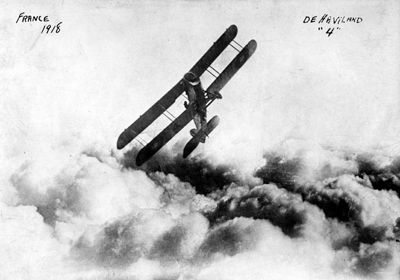

Aircraft developed substantially during the war. They were initially used for observation and reconnaissance, until the French became the first to attach a machine gun to a plane. It was a Dutchman, working for the Germans, Anton Fokker, who provided the solution for firing a machine gun through a propeller. With the development of the fighter plane came the concept of dogfights, and ‘aces’ on all sides achieved celebrity status for their acts of daring, the most renowned being the German, Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. Richthofen, credited with a record eighty kills, was shot down and killed in April 1918.

Bi-plane over France, 1918.

Bomber planes caused damage to major cities such as London, Paris and Cologne. Paris, for example, suffered 266 deaths throughout the war from aerial bombardment, be it aeroplane or zeppelin. In Britain the Royal Flying Corps was an adjunct to both the army and navy, but on 1 April 1918, in recognition of the growing importance of aerial combat, the Royal Air Force was founded.

Damaged German ship after the Battle of Jutland, 1916

On 31 May 1916, the largest sea battle took place – the Battle of Jutland. Chief Admiral of the German High Seas Fleet, Reinhard Scheer, knew full well that Britain boasted the strongest navy, but believed he could lure individual ships into battle and deal with the British fleet one vessel at a time. His grandiose plans however went awry when Britain deciphered the enemy’s communications, discovering exactly what Scheer had in mind. The battle around the Danish waters of Jutland, led by Scheer and his British counterpart, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, proved a cat and mouse affair with no clear victor, although by sheer numbers of ships sunk, the Germans claimed the honours. The clashes of big ships however came to an end. German strategy changed to greater reliance on the submarine. In January 1917, the Germans issued a proclamation that her U-boats would, from thenceforth, attack anything in sight on the east side of the Atlantic, without warning, whether neutral or not. Their idea was to prevent food and supplies reaching Britain. Within a month, German U-boats had sunk five US ships, killing American passengers.

The U-boats were decimating shipping crossing the Atlantic, sinking 25 per cent of British merchant ships bringing in essential supplies and foodstuffs. Admiral Jellicoe warned ‘it is impossible for us to go on with the war if losses like this continue’. Lloyd George’s answer was to implement a system of convoys so that ships would not have to run the gauntlet of travelling alone. Introduced in May 1917, the effect was immediate – the losses to British ships went down from a quarter to one per cent.