World Order (13 page)

Authors: Henry Kissinger

It is a question both sides of the Atlantic must ask themselves. The Atlantic community cannot remain relevant by simply projecting the familiar forward. Cooperating to shape strategic affairs globally, the European members of the Atlantic Alliance in many cases have described their policies as those of neutral administrators of rules and distributors of aid. But they have often been uncertain about what

to do when this model was rejected or its implementation went awry. A more specific meaning needs to be given to the often-invoked “Atlantic partnership” by a new generation shaped by a set of experiences other than the Soviet challenge of the Cold War.

The political evolution of Europe is essentially for Europeans to decide. But its Atlantic partners have an important stake in it. Will the emerging Europe become an active participant in the construction of a new international order, or will it consume itself on its own internal issues? The pure balance-of-power strategy of the traditional European great powers is precluded by contemporary geopolitical and strategic realities. But nor will the nascent organization of “rules and norms” by a Pan-European elite prove a sufficient vehicle for global strategy unless accompanied by some accounting for geopolitical realities.

The United States has every reason from history and geopolitics to bolster the European Union and prevent its drifting off into a geopolitical vacuum; the United States, if separated from Europe in politics, economics, and defense, would become geopolitically an island off the shores of Eurasia, and Europe itself could turn into an appendage to the reaches of Asia and the Middle East.

Europe, which had a near monopoly in the design of global order less than a century ago, is in danger of cutting itself off from the contemporary quest for world order by identifying its internal construction with its ultimate geopolitical purpose. For many, the outcome represents the culmination of the dreams of generations—a continent united in peace and forswearing power contests. Yet while the values espoused in Europe’s soft-power approach have often been inspiring, few of the other regions have shown such overriding dedication to this single style of policy, raising the prospects of imbalance. Europe turns inward just as the quest for a world order it significantly designed faces a fraught juncture whose outcome could engulf any region that fails to help shape it. Europe thus finds itself suspended between a past it seeks to overcome and a future it has not yet defined.

CHAPTER 3

Islamism and the Middle East: A World in Disorder

T

HE

M

IDDLE

E

AST

has been the chrysalis of three of the world’s great religions. From its stern landscape have issued conquerors and prophets holding aloft banners of universal aspirations. Across its seemingly limitless horizons, empires have been established and fallen; absolute rulers have proclaimed themselves the embodiment of all power, only to disappear as if they had been mirages. Here every form of domestic and international order has existed, and been rejected, at one time or another.

The world has become accustomed to calls from the Middle East urging the overthrow of regional and world order in the service of a universal vision. A profusion of prophetic absolutisms has been the hallmark of a region suspended between a dream of its former glory and its contemporary inability to unify around common principles of domestic or international legitimacy. Nowhere is the challenge of international order more complex—in terms of both organizing regional order and ensuring the compatibility of that order with peace and stability in the rest of the world.

In our own time, the Middle East seems destined to experiment with all of its historical experiences simultaneously—empire, holy war,

foreign domination, a sectarian war of all against all—before it arrives (if it ever does) at a settled concept of international order. Until it does so, the region will remain pulled alternately toward joining the world community and struggling against it.

The early organization of the Middle East and North Africa developed from a succession of empires. Each considered itself the center of civilized life; each arose around unifying geographic features and then expanded into the unincorporated zones between them. In the third millennium

B.C.

, Egypt expanded its influence along the Nile and into present-day Sudan. Beginning in the same period, the empires of Mesopotamia, Sumer, and Babylon consolidated their rule among peoples along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. In the sixth century

B.C.

, the Persian Empire rose on the Iranian plateau and developed a system of rule that has been described as “

the first deliberate attempt

in history to unite heterogeneous African, Asian and European communities into a single, organized international society,” with a ruler styling himself the

Shahanshah,

or “King of Kings.”

By the end of the sixth century

A.D.

, two great empires dominated much of the Middle East: the Byzantine (or Eastern Roman) Empire with its capital in Constantinople and professing the Christian religion (Greek Orthodox), and the Sassanid Persian Empire with its capital in Ctesiphon, near modern-day Baghdad, which practiced Zoroastrianism. Conflicts between them had occurred sporadically for centuries. In 602, not long after a plague had wracked both, a Persian invasion of Byzantine territories led to a twenty-five-year-long war in which the two empires tested what remained of their strength. After an eventual Byzantine victory, exhaustion produced the peace that statesmanship had failed to achieve. It also opened the way for the ultimate victory of Islam. For in western Arabia, in a forbidding desert outside the control

of any empire, the Prophet Muhammad and his followers were gathering strength, impelled by a new vision of world order.

Few events in world history equal the drama of the early spread of Islam. The Muslim tradition relates that Muhammad, born in Mecca in the year 570, received at the age of forty a revelation that continued for approximately twenty-three years and, when written down, became known as the Quran. As the Byzantine and Persian empires disabled each other, Muhammad and his community of believers organized a polity, unified the Arabian Peninsula, and set out to replace the prevailing faiths of the region—primarily Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism—with the religion of his received vision.

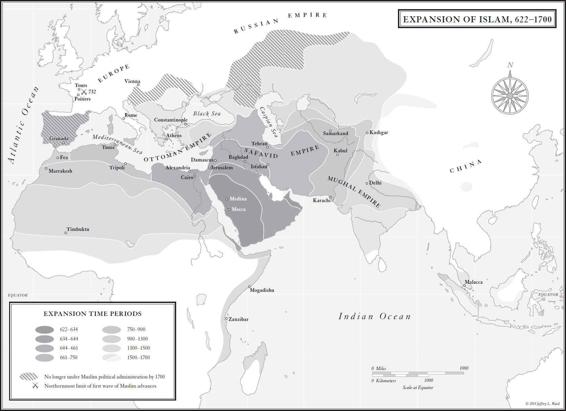

An unprecedented wave of expansion turned the rise of Islam into one of the most consequential events in history. In the century following the death of Muhammad in 632, Arab armies brought the new religion as far as the Atlantic coast of Africa, to most of Spain, into central France, and as far east as northern India. Stretches of Central Asia and Russia, parts of China, and most of the East Indies followed over the subsequent centuries, where Islam, carried alternately by merchants and conquerors, established itself as the dominant religious presence.

That a small group of Arab confederates

could inspire a movement that would lay low the great empires that had dominated the region for centuries would have seemed inconceivable a few decades earlier. How was it possible for so much imperial thrust and such omnidirectional, all-engulfing fervor to be assembled so unnoticed? The records of neighboring societies had not, until then, regarded the Arabian Peninsula as an imperial force. For centuries, the Arabs had lived a tribal, pastoral, seminomadic existence in the desert and its fertile fringes. Until this point, though they had made a handful of evanescent challenges to Roman rule, they had founded no great states or empires. Their historical memory was encapsulated in an oral tradition of epic poetry. They figured into the consciousness of the Greeks, Romans, and Persians mainly as occasional raiders of trade routes and

settled populations. To the extent they had been brought into these cultures’ visions of world order, it was through ad hoc arrangements to purchase the loyalty of a tribe and charge it with enforcing security along the imperial frontiers.

In a century of remarkable exertions, this world was overturned. Expansionist and in some respects radically egalitarian, Islam was unlike any other society in history. Its requirement of frequent daily prayers made faith a way of life; its emphasis on the identity of religious and political power transformed the expansion of Islam from an imperial enterprise into a sacred obligation. Each of the peoples the advancing Muslims encountered was offered the same choice: conversion, adoption of protectorate status, or conquest. As an Arab Muslim envoy, sent to negotiate with the besieged Persian Empire, declared on the eve of a climactic seventh-century battle, “

If you embrace Islam

, we will leave you alone, if you agree to pay the poll tax, we will protect you if you need our protection. Otherwise it is war.” Arab cavalry, combining religious conviction, military skill, and a disdain for the luxuries they encountered in conquered lands, backed up the threat. Observing the dynamism and achievements of the Islamic enterprise and threatened with extinction, societies chose to adopt the new religion and its vision.

Islam’s rapid advance

across three continents provided proof to the faithful of its divine mission. Impelled by the conviction that its spread would unite and bring peace to all humanity, Islam was at once a religion, a multiethnic superstate, and a new world order.

T

HE AREAS

I

SLAM

had conquered or where it held sway over tribute-paying non-Muslims were conceived as a single political unit:

dar al-Islam,

the “House of Islam,” or the realm of peace. It would be governed by the caliphate, an institution defined by rightful succession to the earthly political authority that the Prophet had exercised. The lands beyond were

dar al-harb,

the realm of war; Islam’s mission was to incorporate these regions into its own world order and thereby bring universal peace:

The dar al-Islam

, in theory, was in a state of war with the dar al-harb, because the ultimate objective of Islam was the whole world. If the dar al-harb were reduced by Islam, the public order of

Pax Islamica

would supersede all others, and non-Muslim communities would either become part of the Islamic community or submit to its sovereignty as tolerated religious communities or as autonomous entities possessing treaty relations with it.

The strategy to bring about this universal system would be named jihad, an obligation binding on believers to expand their faith through struggle. “Jihad” encompassed warfare, but it was not limited to a military strategy; the term also included other means of exerting one’s full power to redeem and spread the message of Islam, such as spiritual striving or great deeds glorifying the religion’s principles. Depending on the circumstances—and in various eras and regions, the relative emphasis has differed widely—the believer might fulfill jihad “

by his heart; his tongue

; his hands; or by the sword.”

Circumstances have, of course, changed greatly since the early Islamic state set out to expand its creed in all directions or when it ruled the entire community of the faithful as a single political entity in a condition of latent challenge to the rest of the world. Interactions between Muslim and non-Muslim societies have gone through periods of often fruitful coexistence as well as stretches of antagonism. Trade patterns have tied Muslim and non-Muslim worlds more closely together, and diplomatic alignments have frequently been based on Muslim and non-Muslim states working together toward significant shared aims. Still, the binary concept of world order remains the

official state doctrine of Iran, embedded in its constitution; the rallying cry of armed minorities in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Libya, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Pakistan; and the ideology of several terrorist groups active across the world, including the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).