Work Clean (20 page)

Authors: Dan Charnas

The open workplace.

The walls have come down within the office, too. The old, hierarchical, siloed corporate layouts of corner offices and cubicles have given way to large, airy rooms with long, shared tables and all kinds of communal spaces meant to foster the same kinds of connectivity as the Internet itself. Some 70 percent of office employees now work in open layouts, and according to several studies, the change has been a dismal failure. The supposed benefits to workersâbetter communication, more collaboration, stronger camaraderieâhave paled in comparison to the pitfalls: lack of privacy, more noise, more interruption leading to reduced productivity and diminished morale. For many older workers, the shift to the open office has been an indignity, reminding them more of industrial era sweatshops than a brave new world of work. And for many younger workers who've known no other system, the price of their satisfaction may be a lowered baseline of productivity. In other words, the young folks have no idea how much more productive they could be with some boundaries.

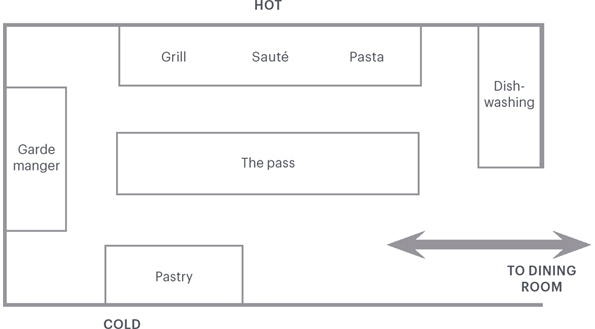

The modern office has become a laboratory for human attention. Ironic, then, that the professional kitchen is a great working model for an open-layout, multitasking environment. Everybody works together on the floor. The chef stands with them at the pass, like a maestro, orchestrating and evaluating the work. Noises, sights, and smells bombard the cooks while they try to focus on cooking.

THE OPEN KITCHEN

But unlike that of the office, the cook's creative work is largely

nonverbal.

One of the reasons that chefs can communicate and create at the same time is that their verbal and nonverbal workâtaking orders and cooking themâare not competing for the same brain space. Similar tasks, like e-mailing and talking, use the same parts of the brain, so they create what neurologists call interference and engender the kind of rapid back-and-forth task switching that studies have shown is so inefficient. But consider a study conducted by French scientists in 2010 that may show a refinement of this notion. They found that the geography of the brain actually

does

engender our ability to take on two similar tasks at a timeâ

just not three.

If we take this particular study to heart, then it does confirm not only the validity of the balanced motion and task chaining we've discussed in earlier chapters, but also suggests the

usefulness of another model for an open-layout,

verbal

multitasking environment that works: the classic newsroom. So maybe our brave new world is just a sleek titanium-and-glass-mobile-phone version of our older one.

The kitchen demonstrates the tension between immersive tasks and process tasks in microcosm, but shows us that we can successfully be part of an interconnected system, be aware, be interrupted,

and still be creative.

Like chefs, we can work clean with our senses. We can use the common sense of chefs, combined with what we know to be true about the brain, to attune and extend our awareness.

TAKE INVENTORY

To transform kitchen awareness into office awareness, we need first to take inventory.

What are the things in your workspace demanding

more

awareness?

Make a list of the communication you tend to miss regularly or on occasion. Do you overlook e-mails? Do you mishear or space out in meetings? Do you take too long to hear when colleagues call to you?

What are the things in your workspace needing

less

awareness?

Do computer and phone alerts interrupt you too much? Do nearby conversations distract you? Do you find that your inner thoughts and daydreams tug at your focus?

The goal of open ears and eyes is not to blast open your walls of focus, privacy, and sanity. Rather it is, as Chef Briggs said, to attune yourself, to set the boundaries properly and give the gate keys to the right people.

Just as Elizabeth Briggs cultivated open ears and eyes as a young chef to acquire the skills necessary for her success, so can you. Survivors in a corporate climate have a kind of radarlike awareness. They ask more questions. They listen to people from other departments. They detect subtle shifts in tone and body language. They pick up cues that tip them off to things that take others by surprise. As a result they become like meteorologists of the political and business climate of the office. If you work in such an environment, ask yourself another question:

What do you want to learn and from whom?

Tune your awareness to those activities and people accordingly.

For those with digital devices, pick three people you want to be more connected or responsive to at work: a boss, a colleague, or an

assistant. For each of these three people, you are going to create “VIP” sonic and visual cues in your personal devices, to help raise your own level of alertness to them.

Unique alerts.

Many smartphones allow you to set a specific ring for certain people. Many computer e-mail programs have “rules” settings that will play a unique tone when an e-mail from a designated person arrives, or let you set the e-mail to display in a particular color. For each of the three people in question, set specific sonic and/or visual cues, or one for all three. Humans are born with the ability to filter out certain voices and sounds. For our personal devices, it's important that we take a little time to program some intelligent, intentional differentiation into them so that we can aid our own ability to discern the important from the irrelevant.

Separate channels.

Another way to differentiate important communication is to put it in its own unique channel, like forwarding these VIPs' e-mails to a separate address, or communicating in a private group on a closed service such as Basecamp or Asana. The most important thing about the separate channel is its exclusivity. Only those three folks have it, and it's the one that you might leave open to alert you when you've closed all the others.

Once you've set up these VIP cues, you can train yourself to be more responsive to them. Have one of your three VIPs help train you. For a day, have that friend call, e-mail, or message you every hour. Whenever you hear or see that friend's message, perform a

physical

action. If you are sitting, stand up. If you are standing, jump up or sit down. Begin to associate a behavior of intention and attention with that stimulus. Rest assured, you won't have to jump up forever! But from that day on, you should be more attuned to those particular sights and sounds.

Test your kitchen awareness with these exercises.

â

For 15 minutes while you cook, also listen to or watch the news on TV, the radio, or the Internet. Then, after those 15 minutes, write down the topic of every story you heard.

â

While you cook, have a conversation with someone for 15 minutes. When time is up, summarize what he said.

â

Try to cook with your ears and nose as well as your eyes. What sounds do you hear that tell you to give a pan some attention? Can you guess the level of doneness of a dish from its smell?

The kitchen is a great place to practice balancing internal and external awareness.

UP PERISCOPE

Today's work environment demands constant awareness, and it takes great strength to pull away for even an hour or two to focus on an immersive project. The following habit is a great way to honor your need for focus by regimenting and constraining communication.

1.

Set an hourly chime, either on a watch, your computer, or your phone.

2.

Create a list of channels that you feel you must check when that chime rings to be in proper communication.

3.

Turn off alerts and the ringer on your phone and close your e-mail and instant messaging programs. You can even disconnect from the Internet by shutting down your browser or turning off your Wi-Fi. Do whatever you feel you need for your own peace of mind.

4.

When the chime rings, grab your checklist and check in quickly on all your channels. Give yourself 5 or 10 minutes to process that communication, unless something urgent has come up. At the end of that check-in session, retreat from your connectivity again.

You may already practice some version of this “up periscope/ down periscope” habit. This exercise adds intentionality to these actions:

Youânot other people, and not your technologyâ

set the rules for engagement with your work environment.

Some folks who possess more than one device might want to dedicate one of them to connectivity, and reserve the other purely for work. The act of physically turning from one device to another creates powerful shifts in attention.

Let's say that you aren't in a position to make the rules for your workplace interactions. You may, for example, work at a company that insists all communications happen through a particular messaging system and mandates that you stay connected all the time. We can't control what companies expect of us in our communication. We can't control when people will approach us to chat. But we can all make and negotiate simple requests, even if we can't control people's responses to them. These kinds of requests may include:

â

Asking people to honor a “Focusing: Do Not Disturb” card on your desk, wall, door, or computer monitor.

â

Asking colleagues to say your name or touch your arm first if they want to get your attention during a moment of concentration.

â

Asking your boss for permission for pauses in connectivity so that you can complete your work.

â

Asking colleagues to contact you only during business hours.

The e-mail auto-responder is a powerful and often underused tool to set others' expectations about your availability. They're not just for vacations. Some college professors use them on weekends to set

students' expectations. Some people use them for a few hours a day when they need time “off the grid.”

Interruption is a fact of life in the workplace, but we can make peace with interruption. When our focus gets pulled, we can regain it by borrowing a technique from the Eastern tradition of mantra meditation. A mantra is a sound or vibration. A mantra meditation asks the practitioner to repeat that sound silently or aloud to herself for a certain period of time.

The main complaint of new mantra meditators is that “it doesn't work”âmeaning that they start thinking the mantra and before they know it, they're worrying about work, or replaying a scene in their head from a TV show they watched the previous day, or thinking about where to get their car fixed.

To that we say: “Congratulations!” It's working.

Here's how it goes: You think the mantra. Your focus gets pulled. You notice after a while that you're not thinking the mantra anymore. You start thinking the mantra again. The process repeats. You don't get angry at yourself. You don't tell yourself and others that it's not working. You don't curse your wonderful, restless mind. You just accept that this is the way your mind works, with thoughts crashing in like waves on the ocean. Meditators commit to surfing those waves rather than getting pounded by them.

Keep a mantralike focus on your work, but accept the inevitability of interruption. When you are interrupted, you don't get mad. You give thanks that you are alive to be interrupted. You give a few moments to the person interrupting you. You stop what you are doing to help, or you ask them to wait. Then you come back to your mantra, to your work.

And in those times when your inner equilibrium becomes unable to compete with the interruptions, as with meditation, you go find a quiet place.

A chef's reprise: Mastery and awareness

At the end of Elizabeth Briggs's culinary fundamentals class, 15 weeks after her students first waddled in, their gait becomes a strut. Briggs notices that as her students' sense of confidence grows, so does their awarenessâtheir ability to hear and see and be in the moment in her kitchen.

When they first arrived, the students “zoned in” on tasks because they were still learning the basics, just trying to get through class without cutting or burning themselves. “If I can get my students to work through that insecurity,” Briggs says, “they usually have an awakening around day 18.”

As they begin to get comfortable with their tasks, their sensitivity opens up. “They can begin to feel and see and hear more. They are more open to communication, and they have that sense of âI've arrived.'”

She tells them: “If I had measured your height on the door frame on the first day of class, you'd see now that you've all grown 3 inches taller.”