Wonder Woman Unbound (26 page)

Read Wonder Woman Unbound Online

Authors: Tim Hanley

Detective Comics

#359, cover by Carmine Infantino and Murphy Anderson, DC Comics, 1967

The first appearance of Barbara Gordon as Batgirl. As a nonsuperpowered crime fighter, Batgirl was the feminist heroine Diana Prince should have been.

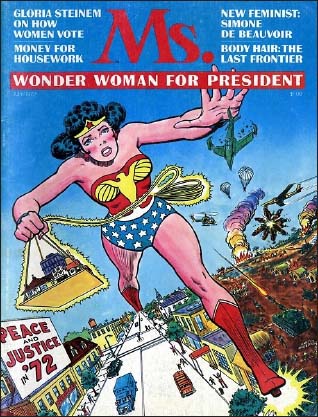

Ms. #1,

1972

Wonder Woman graces the cover of the first issue of

Ms.

magazine. The issue reprinted a portion of her Golden Age origin story.

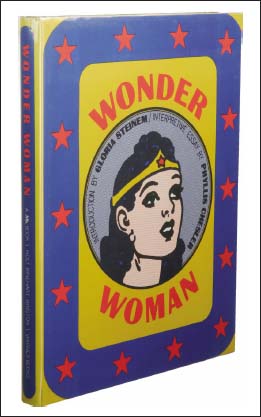

Wonder Woman,

with an introduction by Gloria Steinem, 1972

A collection of Golden Age Wonder Woman stories published by

Ms.

magazine to celebrate her return to her Amazon roots. IMAGE COURTESY OF HERITAGE AUCTIONS (

WWW.HA.COM

)

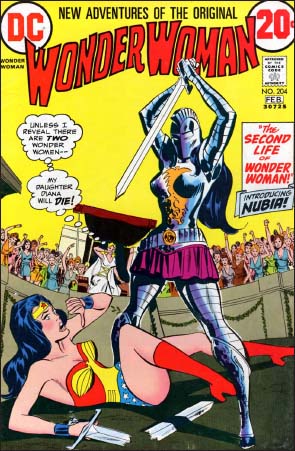

Wonder Woman

#204, cover by Don Heck and Dick Giordano, DC Comics, 1973

After four years as a normal human without superpowers, the Amazon Wonder Woman returned.

The Newspaper of the Los Angeles Women’s Centre,

cover by C. Clement, 1973

A cartoon in a feminist paper had Wonder Woman advocating for women’s sexual health.

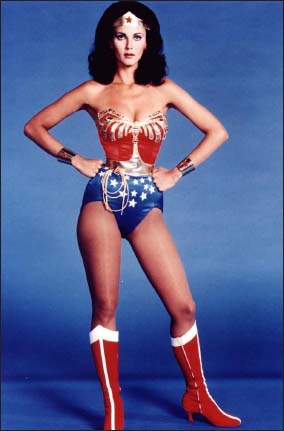

Wonder Woman

TV show publicity photo, 1977

Lynda Carter as TV’s Wonder Woman. Carter’s portrayal became the definitive version of the character, cementing Wonder Woman as a pop culture icon.

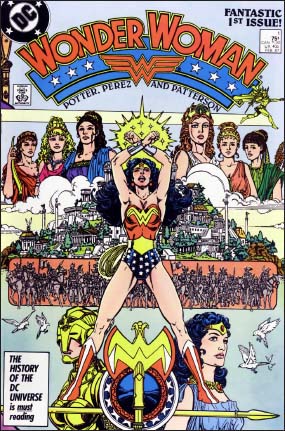

Wonder Woman

#1, cover by George Pérez, DC Comics, 1987

Wonder Woman was relaunched as a brand-new series with a premier artist and a strong feminist slant.

Wonder Woman

#190, cover by Adam Hughes, DC Comics, 2003

In one of the biggest Wonder Woman stories of the Modern Age, she got a haircut.

Justice League

#12, cover by Jim Lee, DC Comics, 2012

In another big Modern Age Wonder Woman story, she hooked up with Superman.

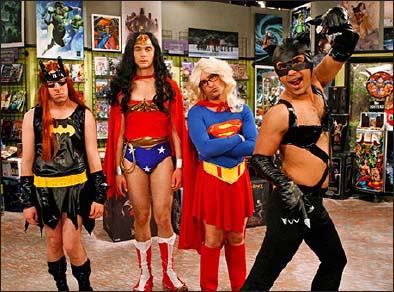

The cast of

The Big Bang Theory

as superheroines, publicity photo, 2010

Howard (Simon Helberg) as Batgirl, Sheldon (Jim Parsons) as Wonder Woman, Leonard (Johnny Galecki) as Supergirl, and Raj (Kunal Nayyar) as Catwoman. SONJA FLEMMING / CBS

INTERLUDE 2

Letters and Advertisements

W

onder Woman’s

intended audience over its first few decades is very clear in retrospect. Marston stated several times that he aimed the book at boys, trying to teach them to submit to the loving authority of women. In the 1950s, extra features like “Marriage a la Mode” and “Gems of Destiny” suggested that DC Comics was trying to appeal to female readers. The target audience reveals a lot about

Wonder Woman

and the aims of the creators and editors behind the book, but what it can’t show is who actually read the series.

Some fairly safe assumptions can be made about the age range of the audience, since superhero comics in the Golden and Silver Ages were read primarily by kids. In the 1960s, Marvel comics brought in an older crowd of teen readers as well, and by the end of the decade DC was trying to get the same demographic, but there aren’t any exact figures. Data about comic book readers in general from the early decades of the industry is fairly minimal, much less for specific series. There are no numbers out there that give a clear idea of who was reading

Wonder Woman,

but hints of this information can be found in other ways.

Letter Columns

Wonder Woman

’s letter column changed a lot over the years, going through several titles and a big demographic shift. Initially the column was called “Wonder Woman’s Clubhouse,” and young kids would write in to Wonder Woman herself. They’d ask Wonder Woman questions about her life or tell her about the fan clubs they’d started. Most of the columns consisted of several short letters, with replies from Wonder Woman.

In 1965, the content changed. Instead of several short letters to Wonder Woman from little kids, there were two or three longer letters addressed to the editor, written by older readers, at least in their early teens. These more substantial missives addressed issues like continuity, mythology, or art and storytelling techniques.

*

This format became the norm and lasted through many name changes. The column became “Wonder Woman’s Readers Write!” in 1967, then “The New Wonderful World of Wonder Woman” late in 1968, followed by “Wonder Woman’s Write-In” in 1971, “Princessions” in 1972, and “Wonder Words” in 1974. “Wonder Words” actually stuck, and it lasted well into the 1980s.