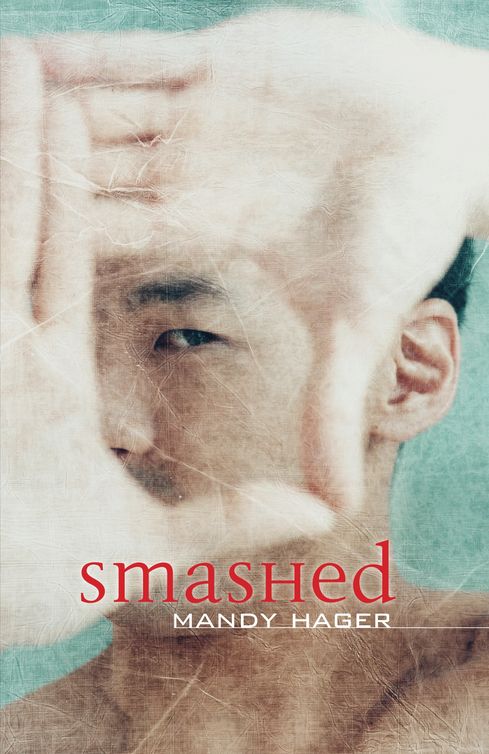

Smashed

Authors: Mandy Hager

To Rose, with all my love —

this one’s for you

Half-title

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgments

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

About the Author

Copyright

With thanks to Jane Parkin, for her expert advice; Greg Clark, for sharing his time and expertise; the DARE Foundation of New Zealand for their support and faith, especially Adela Jones, Gabrielle Carroll and the consultative group; Jenny Hellen and the team at Random House; my family, for their ongoing support and love; and my parents, Kurt and Barbara Hager, for their remarkable genes

and

nurturing!

W

e’re all just puppets — and the only way to handle this completely gutting fact is to try to figure out the logic of our puppeteer. I don’t mean God or Yahweh or Allah or whatever else you want to call him (or her — Mum’d call me sexist if I don’t say that). I’m not sure if I believe in one Supreme Being. It’s

genes

I mean … and you can guarantee one totally depressing thing. Genes don’t give a damn about the happiness of puppets.

Take Dad — IQ of a genius, heart of an artist, but his

genes

doom him to the life of an accountant. He’s stuck inside his dreary number-crunching world because the genes his Chinese parents passed on to him mark him outwardly and sentence him to follow

their

ideas of what is suitable. If he’d been born big-nosed and white he’d have been okay — could’ve gone to art school and followed through his childhood dream. But no, he had to follow in his father’s footsteps to bring his family

‘pride’, not shame. Only now Dad’s up till late most nights, indulging his shameful longings in his shed.

Not that Mum minds. Her genes commit her to a life of revolution — fiery red-haired Irish, with a mood to match. She’s all Dad’s artistic dreams and passions rolled up into one stroppy woman, and I reckon he married her as one big finger to his Chinese past. Made for crazy children too — their two genetic codes are so different that, when mixed, my and Rita’s features separated like oil and water in totally outrageous ways.

I got stuck with Dad’s IQ and all the Asian-looking genes, including some weird throwback to the land of elves. The IQ by itself would be okay, but mixed with geeky Chinese looks I’m nothing but a cliché — the puny, nerdy Asian guy who’s top at school. And I’m not just saying this cos lots of the TV shows and movies have turned the geek into some kind of hero. No, the truth is those fake TV geeks (computer-obsessed geniuses, who everybody thinks are cool) bear no relation to the tragic life of geeks out in the real world. In

my

world, geeks are still the last ones picked at games (especially games that lead to sex) and, truthfully, we lack the social skills and confidence to try to play …

Now Rita, she’s a real mix. She’s got the most amazing eyes — serene green that’s marbled with burnt

orange and small flecks of gold. Genetically they’re straight from Mum. So is Rita’s hair. But while red frizzy hair seems quite at home above Mum’s gangly freckled frame, on Rita it looks plain bizarre — this tiny suede-skinned fourteen-year-old girl with clown hair.

Today she looks completely odd — thigh-length stripy socks with my old running shoes, a yellow polka-dotted skirt and a t-shirt that says ‘F**k The War!’ We’re waiting at the bus stop for a ride to town and the bus is twenty minutes late — or else was early, and we missed it. I hate that.

Half the neighbourhood is waiting too but, Andrew Mathers’s mum aside, we’re standing here like we’re alone. Not a nod, not a wink. I know it’s not a good idea to bare your teeth at a baboon — it takes it as a major threat — so smiling’s out to anything that has a swollen bright-red butt, but even Rita and I act like strangers to each other here. Why is that? It’s not like I hate her. For a sister she is pretty cool. Weird — no doubt of that — but cool.

She’s watching Mrs Mathers now, who’s gobbing on her handkerchief and wiping breakfast scum off Andrew’s cheek. The poor kid’s ears are infra-red. But Rita’s moving in now; she squats down beside him till her eyes meet his. ‘Hey Andy, I like your bag.’ She tweaks the little teddy bear pinned to his backpack, and the way she

holds that wee kid’s gaze calms him right down. She’s just like that — she’ll let the water run cold in the shower while she rescues drowning spiders from the drain, and once she even packed up all her favourite toys and took them to the hospital as presents for the sick kids there at Christmas. Me, I’d be calculating how much each toy cost Mum and Dad to buy, and deducting ‘wear and tear’ to figure out if they got their money’s worth before Saint Rita of the Underdogs gave them away.

That’s another thing about genes — they dictate the way we act. I know there’s all the arguments about ‘nature versus nurture’ (or as my friend Carl puts it:

losers versus boozers

) but they now reckon the things your family and environment can influence are already laid down in your genes. How or where you’re raised just helps turn each gene ‘off’ or ‘on’. Carl’s living proof of this. No matter what his parents try, he’s loco, crazy, ADHD. They could’ve brought him up in Disneyland, and hired the world’s best child psychologists, but none of it would have made a scrap of difference. The guy’s just programmed to make trouble and that’s that.

At last the bus sweeps around the corner. And only seconds later a souped-up car wheelies round the corner too, nearly wipes itself out on the bus and swerves dangerously across the road and back again. A shaggy

blond head appears out the window. ‘Einstein!’ Carl yells, grinning like a lunatic.

Every single person at the bus stop turns around to see who he’s talking to, and all I can do is thank the cosmic forces (who may or may not be anything to do with God) that no one except Rita knows that he means

me

.

Now the driver’s pulled his car over. It’s Don, my oldest schoolmate, and a slightly calmer co-conspirator of Carl’s. Carl flings the passenger door open and leaps out, jiggling up and down on the spot as though he’s riding an invisible horse. He’s singing

‘They may put me in prison but they can’t stop my face from breakin’ out’

like Willy Nelson. The whole cowboy ‘thang’ is one of Carl’s favourite acts, and it kind of suits him, cos he’s got this dreadful eczema that makes his skin look dry and leathery and middle aged.

The bus driver glares at me and grunts, ‘You coming on?’ I just shrug. It’s painfully clear by now that these two idiots do know me and the whole busload of passengers are waiting for my next humiliation. So I grab Rita’s hand as she’s about to push past me, and mutter to the driver, ‘We’re right, thanks.’ My long-dead Chinese grandmother would be proud of me. Even in the hellfire of eternal embarrassment, I’m still polite.

Rita doesn’t seem to care. She’s laughing at Carl,

who’s now doing a scarily good impersonation of Michael Jackson moon-walking (if you ignore the fact that he’s white, blond and still has a nose).

With the bus gone, Don’s excitement overflows. ‘What ya reckon, Toby? I worked till after two this morning, and when I finally got her going I woke the whole damn neighbourhood.’ He strokes the paintwork of his car as if it were a woman’s thigh. It’s so deeply sensual, I almost blush.

‘Yeah, cool.’ I try to sound enthused, but cars don’t do it for me. Still, the last thing I want is to kill Don’s moment. This old heap is the only thing he feels good about, and fixing it up may well be the climax of his sad-arsed life.

If Don is the puppet of

his

family’s genes, he’ll be trucking down the road to hell with an empty whisky bottle any day now. It would be nice if I was joking, but it’s true. Those boozy parents of his doomed him from the start. It’s little wonder he looks on alcohol as his best friend when it’s been the driving force for both his parents since before he and Danica, his sister, were even born. Still, he’s a good mate, Donald Donaldson. I’d trust the ugly mongrel with my life.

‘Climb in,’ Don offers, gesturing so grandly you’d think he’s offering us the world. ‘Where’re you guys going?’

‘Library,’ Rita answers. She clambers under Carl’s arm

and into the junk-filled back seat. ‘Nice ride,’ she says to Don, and he smiles so wide his ears go pink.

Inside it smells like engine oil, and the headlining is smeared with grease. But it’s going, and Don made it that way, so I settle back against a box of spare parts to enjoy the ride.

‘What ya going to the book place for?’ Carl’s making stupid faces at Rita through a cracked mirror on the sun visor, and he winks at her, which makes her giggle.

‘Swot.’ I don’t bother to explain this further. Carl can’t resist rubbing in the fact I’m at university although I’m only seventeen.

‘Ewwww!’ Carl crows. ‘Young, you’ve gotta start taking your life a little more seriously …’ He’s firing up again — I can tell by the maniacal light that comes into his eyes. It’s almost like you can see the chemical changes taking place in his brain and hyping him up. He spins around in his seat, grabbing at the seatbelt around his neck as though he’s fighting off a rattlesnake. ‘Have you phoned Jacinta yet?’ He’s trying to wiggle his eyebrows suggestively, but the skin of his brow is stretched tight from his eczema and he looks like some old Hollywood hag who’s had one too many facelifts.

Rita’s watching way too closely. She knows I’ve liked Jacinta Matthews for a whole year. She also knows I’ve

never had the guts to ask her out. Don’s watching in the rear-view mirror now as well. He can tell the answer’s no without me even opening my mouth.

‘Oh man — the party’s on tomorrow night! I bet a whole ten bucks on you. You promised me you’d make the call.’ Don’s gaze flicks to the road, then back to me. ‘I don’t get it. She’s hot for you. You only gotta look at her and she nearly faints.’

In the passenger seat Carl is loving this, re-enacting every word that’s said in a strange little stage play all of his own. Right now he’s swooning across the seat, his straggly locks on Don’s greasy shoulder. His head lolls back, so he’s leering straight at Rita as he purses up his lips and kisses Don’s clearly unwashed ear. ‘Oh Toby-woby,’ he sighs pathetically.

Don throws the car down a gear and brakes so hard that Carl’s forcibly jerked forward off his shoulder. This doesn’t stop him, though. He breaks into that infuriating country and western twang again, singing at the top of his phoney cowboy breath,

‘If the phone don’t ring, baby, you’ll know it’s me.’

Rita’s killing herself laughing, but she knows how much I hate this stuff. She pats my arm. ‘Poor Toby-woby,’ she purrs. Then she settles down and asks, ‘So where’s the party?’

‘Lance Pagoli’s place,’ Don says. ‘His eighteenth.’

‘Cool,’ she says. ‘Can I come too?’

I’m just about to give a clear-cut ‘No’ when

big-mouthed

Don gets in first. ‘Don’t see why not. He’s invited half the neighbourhood.’

‘Cool!’ Rita knows better than to meet my eye. Instead she plugs herself into her iPod, swaying to the music with a smug grin lighting up her face.

Stuff Don — this is what I

didn’t

want. It’s bad enough going to a party and being voted the biggest loser without my little sister being there to see. The thought of her witnessing Jacinta Matthews chewing me into mincemeat is too much.

I pull her iPod earplugs out. ‘No,’ I say, ‘you can’t come.’

You’d think I’d sentenced her to death, the way her eyes smart with tears and her chin gets this tragic wobble on. I hate it when she cries. If I thought she was just putting it on it’d be okay, but no — it’s obvious she’s really hurt.

Carl’s seen it too. The trouble with these mates of mine, we’re more like family than friends. We’ve known each other since the two of them took me under their wing in Year 9 — me, some freakish kid who’d skipped two years, and them, the biggest trouble-makers in the

school. We’re a dysfunctional family, for sure, but when one of us is hurt, we all hurt. I guess that counts for Rita too. And Carl’s not one to go for subtlety — now he’s howling like his heart’s been broken, grinding his fists furiously into his eye sockets to make the point. ‘Oh pwease, big meany-pants …’

His fists have left his eyes all red and watery, and he’s starting to lose control. He’s rocking from side to side on the seat, forcing Don up against the car door and distracting him from driving.

Don elbows him away, but Carl starts slapping at him so incessantly that Don has to pull over to the side of the road. ‘Cool it, Carl. Did you forget to take your drugs?’

Carl’s face breaks into moralistic outrage. ‘It’s not nice to pick on sick people,’ he lectures, mimicking our old school principal. ‘It’s vewy-vewy-un-PC.’ He laughs like a nutter and clambers over the seat until he’s wedged between me and Rita. ‘Psssst!’ He digs Rita in the ribs. ‘Wanna buy some real good shit?’ He shoves his hand into his pocket and then opens it to her. There, cushioned on his grubby palm, lies one unassuming little pill.

‘You

didn’t

take it, you idiot!’ I snatch the Ritalin from his hand and hold it up close to his face. ‘Take it now. Or else …’

‘You gonna make me, pilgrim?’ He dives under my

arm and throws himself back towards the passenger seat, his feet flying so close to Rita’s face that I have to block him with my arm.

As Carl flips around into his seat again, Don gives him one good thump. ‘Settle down.’

Carl clutches his arm, slithering down off his seat like he’s losing consciousness. ‘Tell Maw,’ he gasps,

cowboy-style

, ‘tell her not to … sell the ranch.’ He’s now crumpled up into the foot well, pretending he’s completely dead.

I’m still holding his medication, and I’m beginning to wonder if it’s just this one dose he’s missed. Rita’s eyes are so wide I can see the whole circle of her iris set against the white. She knows what Carl’s like — has seen performances like this before — but in the confines of the car it’s claustrophobically intense.

She takes the Ritalin from my hand and leans forward, talking to him with the same reassuring voice she used on Andrew Mathers at the bus stop. ‘Carl, please — just take the pill.’

He turns his face to her, grinning like a demon. ‘Tell you what!’ He untangles himself, sits up as though nothing has happened, and turns to me. ‘I’ll take that pill if you promise to phone Jacinta and ask her out!’

Don lets out a bark of a laugh, and I can see I’ve been backed into a corner by my two best friends. There’s

no point prolonging this. I may have an IQ that’s forty points higher than either of them (and probably more like sixty in the case of poor old Don), but when it comes to street smarts these guys leave me shredded in the dust.

‘Okay.’