Wm & H'ry: Literature, Love, and the Letters Between Wiliam and Henry James (3 page)

Read Wm & H'ry: Literature, Love, and the Letters Between Wiliam and Henry James Online

Authors: J. C. Hallman

Tags: #History, #Philosophy, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #Biographies & Memoirs, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Arts & Literature, #Modern, #Philosophers, #Professionals & Academics, #Authors, #19th Century, #Literature & Fiction

passionate

desire for a reformation in my bowels.

I see in it not only the question of a special

localized affection, but a large general change

in my condition & a blissful renovation of my

11

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 11

9/4/12 6:26 PM

life—the reappearance above the horizon of

pleasures which had well-nigh sunk forever

behind that great murky pile of undiminishing

contingencies to which my gaze has so long

been accustomed. It would result in the course

of a comparatively short time, a return to

repose—reading—hopes & ideas—an escape

from this weary world of idleness.

Wm was not oblivious to the sly pun, and offered his

own in return. He called the story a “moving intesti-

nal drama,” a characterization H’ry judged happily

termed.

Even after the comic annoyance of youthful con-

stipation, the correspondence maps the trajectory of

the brothers’ work. They each settled into philoso-

phies and aesthetics, and each made consciousness a

feature of their investigations. Wm wanted to pinpoint

consciousness or at least find a way to describe it. H’ry sought to depict it, even in his letters. His epistolary

output exploded with illness—he wrote

more

when

he was sick. In 110, the frenzied letters describing his latest digestive episode (a problem with his “physical consciousness”), the same letters that brought Wm

12

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 12

9/4/12 6:26 PM

charging across the Atlantic to his doom, now depicted

H’ry’s raging interiority, the “constituted conscious-

ness” that he had only recently described as the true

novelist’s “immense adventure”:

But my diagnosis is, to myself, crystal clear—

& would be in the last degree demonstrable if

I could linger more. What happened was that

I found myself at a given moment more &

more beginning to fail of power to eat through

the daily more marked increase of a strange

& most persistent & depressing stomachic

crisis: the condition of more & more sickishly

loathing

food. This weakened & undermined

& “lowered” me, naturally, more & more—&

finally scared me through rapid & extreme loss

of flesh & increase of weakness & emptiness—

failure of nourishment. I struggled in the wil-

derness, with occasional & delusive flickers of

improvement . . . & then 1 days ago I collapsed

and went to bed.

13

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 13

9/4/12 6:26 PM

On October 13, 1, H’ry scribbled out a quick reply

to Wm’s previous two letters. The first of these had

described a battle with dysentery that Wm had waged

after a country rest, and the second made a peculiar

request: could H’ry please obtain a perfect sphenoid

bone and send it at once to Cambridge? Wm had re-

cently become assistant professor of physiology at

Harvard, and he was attempting to take advantage of

H’ry’s yearlong stay in Paris to obtain a particularly

difficult-to-procure item. H’ry did not ask why a pris-

tine specimen of the butterfly-shaped skull bone was

required. He simply made inquiries and set off the

next morning for Maison Vasseur, the very best place

in Paris for such things. M. Vasseur refused the order.

A perfect sphenoid detached from the head was simply

impossible to get, he claimed. Of course, a badly dam-

aged sphenoid might be found at a bric-a-brac shop, but

no perfect sphenoid could ever be purchased separate

from its head. As it happened, M. Vasseur had whole

heads for sale, and he offered H’ry a “

très-belle tête

” for thirty-five or forty francs. H’ry hesitated, as Wm had

specified the sphenoid only. He decided to report back

14

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 14

9/4/12 6:26 PM

and request further instruction. His letter of October 13

drily related his visit to Maison Vasseur, and he apolo-

gized for having come up empty-handed. “If you wish

it I will instantly purchase & send one,” H’ry wrote, meaning an entire head, sphenoid and all.

Wm sent him shopping. H’ry tried again at the es-

tablishment of Jules Talrich, but the trip proved a dis-

appointment. “The wretched Talrich” attempted to

obtain an independent sphenoid, but discovered in

the end that M. Vasseur had been correct. Indepen-

dent sphenoids could simply not be had. Talrich, too,

offered H’ry an entire head, but pointed out that a

French head sent across the ocean in a parcel as large

as a hat would probably wind up costing more than an

American cranium.

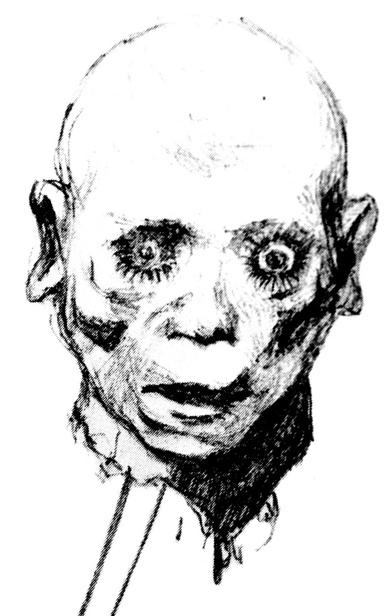

Wm’s fascination with heads was long-standing.

Early in life he had become preoccupied with a photo

of a purported death mask of Shakespeare. “It is a

superb head,” he told H’ry, and he followed up several

months later—when H’ry failed to reply—with the

insistence that “the mask is extremely interesting.”

Around the same time, Wm sketched the head of a

cadaver in Germany, an image that seemed to project

a dark mood he famously suffered in the late 10s.

15

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 15

9/4/12 6:26 PM

And after Wm turned to psychology, he claimed that

our sense of self, our “Self of selves,” is perceived to

consist of motions “in the head or between the head

and throat.”

“I would give my head to be able to use it,” H’ry

wrote in 1, revealing that, for both brothers, inter-

est in heads was merely the beginning of interest in

what was happening

inside

the head. “Mysterious & incontrollable (even to one’s self ),” H’ry wrote four

16

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 16

9/4/12 6:26 PM

years later, reflecting on his progress as a writer, “is

the growth of one’s mind.” Interest in consciousness

mostly ran from older brother to younger. Starting

in the late 10s, with the contract to produce

The

Principles of Psychology

,

Wm wrote a series of essays that inched closer and closer to a definitive statement

on consciousness. H’ry read each as they appeared.

In 1, “Brute and Human Intellect” cataloged two

kinds of thinking, reasoning and narrative, the lat-

ter described as “a procession through the mind of

groups of images.” In 13, “On Some Omissions in

Introspective Psychology” chastised psychological au-

thorities for ignoring the inner life and tried imagery on the problem of thought: “Our mental life, like a bird’s

life, seems to be made of an alternation of flights and

perchings.” And several years later, H’ry reported that

he had been “fascinated by the

Hidden Self

,

in

Scribner

,”

in which Wm used a review of Pierre Janet to sneak

up on the metaphor that would transcend him: “Our

minds are all of them like vessels full of water, and

taking in a new drop makes another drop fall out.”

By 10, H’ry admitted that he “quite yearn[ed]”

for

The Principles of Psychology

. Wm ordered his brother a copy two days after the publication date finally ar-17

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 17

9/4/12 6:26 PM

rived. “Most of it is quite unreadable,” Wm warned, and

steered H’ry toward the “Chapter on Consciousness

of Self.” Wm had already coined the phrase “stream of

consciousness” by then, but the image emerged fully

formed only here:

Consciousness, then, does not appear to itself

chopped up in bits. Such words as “chain” or

“train” do not describe it fitly as it presents itself

in the first instance. It is nothing jointed; it flows.

A “river” or a “stream” are the metaphors by

which it is most naturally described.

In talking

of it hereafter

,

let us call it the stream of thought

,

of

consciousness

,

or of subjective life.

Wm knew that literature had trail-blazed conscious-

ness in more than just the poems of Matthew Arnold.

An early “debauch on french fiction,” as he described

it to H’ry, led him to conclude that “French literature

is one long loving commentary on the variations of

which individual human nature is capable.” The appre-

ciation of variations, of variety, would go on to become

a major theme of Wm’s career. Whether considering

experience, personality types, religion, or truth, the appreciation of variety as a value was central to whatever

18

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 18

9/4/12 6:26 PM

melioration people could hope to effect. “The notion

of the ‘one’ breeds foreignness,” Wm wrote later in life,

“and that of the ‘many’ intimacy.”

The problem, he claimed, was that as individual

consciousnesses we were all stuck in our heads, stuck

in

oneness

. No one could ever truly

know

the mind of another; we were “blind to the feelings of creatures

and people different from ourselves.” But even this

observation had come first from literature. Wm had

been particularly struck by Robert Louis Stevenson’s

essay “The Lantern Bearers” (to H’ry: “The true phi-

losophy is that of Stevenson”), which claimed that “no

man lives in the external truth, among salts and acids,

but in the warm phantasmagoric chamber of his brain,

with the painted windows and the storied walls.” Wm

quoted pages of the essay in an essay of his own, and

concluded that only the “sphere of imagination”—

creative work—offered true hope of breaching the

membrane that kept us separate and discrete.

Which perhaps explains why Wm had first been

drawn to art—and why he was slow in coming around

to the science of psychology. “I believe I told you in my last that I had determined to stick to psychology or

die,” he wrote in 13. “I have changed my mind.” H’ry

19

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 19

9/4/12 6:26 PM

was saddened at the news. “There seems something

half tragic in the tone with which you speak of hav-

ing averted yourself,” he replied. Although the letters

sometimes make it seem that H’ry was the source for

psychological insight—for example, an 1 letter in

which H’ry hopes Wm’s young son will “bloom with

dazzling brilliancy” sounds a whole lot like the “bloom-

ing, buzzing confusion” Wm used a few years later to

describe the consciousness of a child—far more often

it’s apparent that H’ry slyly mined Wm’s work for his

fiction.

That H’ry, too, had become preoccupied with con-

sciousness is evident even from his early stories. “A

Most Extraordinary Case” (Wm: “read it with much sat-

isfaction”) dwells on characters emerging from sleep

or experiencing semi-intoxicated states, and the plot

of “The Sweetheart of M. Briseux” orbits a painting

described as “the picture of a mind, or at least of a

mood.” H’ry was eternally fascinated by Wm’s progress

as a psychologist, and he tracked it carefully when he

wasn’t subtly fostering it. He once asked after a class

on physiological psychology that Wm taught, and a few

years later he offered heartfelt thanks for a now-lost

letter that described a “brain-lecture.” For his part,

20

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 20

9/4/12 6:26 PM

Wm vacillated in his response to H’ry’s fiction. He once

praised the “successive psychological steps” in another

early story, “Poor Richard” (Wm had read and critiqued

an early draft), and in 1 he claimed there would be

no better “delicate national psychologist” than H’ry,

should he become one. More often, however, Wm was

baffled by H’ry’s work. He claimed to read fiction for

“refreshment,” and while he allowed that the “‘

étude

’

style of novel” should not be judged by a standard of

refreshment, he could not keep himself from chastising

his brother. He eventually pleaded with H’ry to avoid

“psychological commentaries” entirely.

H’ry did not—and it may be fair to characterize his

entire oeuvre as a prolonged project of extending Wm’s