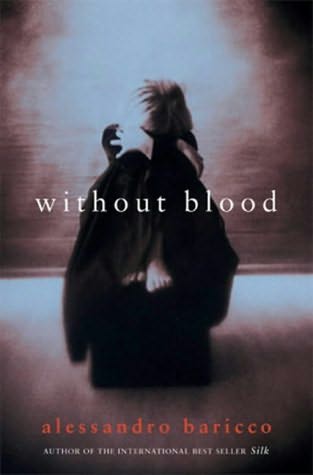

Without Blood

Authors: Alessandro Baricco

This book has been optimized for viewing

at a monitor setting of 1024 x 768 pixels.

A L E S S A N D R O B A R I C C O

W i t h o u t B l o o d

Alessandro Baricco was born in Turin in 1958 and still makes his home there. The author of four previous novels, he has won the Prix Médicis Étranger in France and the Selezione Campiello, Viareggio, and Palazzo al Bosco prizes in Italy.

A L S O B Y A L E S S A N D R O B A R I C C O

An Iliad

City

Silk

Ocean Sea

W i t h o u t B l o o d

W i t h o u t B l o o d

A L E S S A N D R O B A R I C C O

Translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein

V I N T A G E I N T E R N A T I O N A L

Vintage Books

A Division of Random House, Inc.

New York

FIRST VINTAGE INTERNATIONAL EDITION, MARCH 2008

Translation copyright © 2004

by Alessandro Baricco

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in Italy as

Senza sangue

by Rizzoli, Milan, in 2002. Copyright © 2002

RCS Libri S.p.A., Milano. This translation originally published in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 2004.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage International and Colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows: Baricco, Alessandro [date]

[Senza sangue. English]

Without blood / Alessandro Baricco ; translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein—1st American ed.

p. cm.

I. Goldstein, Ann, 1949– . II. Title.

PQ4862.A6745S4513 2004 853'.914—dc22 2003058917

eISBN: 978-0-307-38936-7

v1.0

The events and persons mentioned in this story are imagi-nary. The frequent choice of Spanish names is due purely to their music and is not intended to suggest a historic or geographical location of the action.

O n e

The old farmhouse of Mato Rujo stood

blankly in the countryside, carved

in black against the evening light, the only stain in

the empty outline of the plain.

The four men arrived

in an old Mercedes. The road was

pitted and

dry—a poor country road. From the farmhouse,

Manuel

Roca saw them.

He went to the window. First he saw the column of dust

rising against the corn. Then he heard the sound of the engine.

No one had a car anymore, around

here. Manuel

Roca knew it.

He saw the Mercedes emerge in the distance and

disappear

behind a line of oaks. Then he stopped

looking.

He returned to the table and

placed a hand on his daughter’s

3

head. Get up, he told

her. He took a key from his pocket, put it

on the table, and nodded at his son. Yes, the son said. They were

children, just two children.

At the crossroads where the stream ran the old Mercedes did not

turn off to the farmhouse but continued toward Álvarez instead.

The four men traveled

in silence. The one driving had on a sort

of uniform. The other sitting in front wore a cream-colored

suit. Pressed. He was smoking a French cigarette. Slow down,

he said.

Manuel

Roca heard the sound fade into the distance toward

Álvarez. Who do they think they’re fooling? he thought. He saw

his son come back

into the room with a gun in his hand and

another under his arm. Put them there, he said. Then he turned

to his daughter. Come, Nina. Don’t be afraid. Come here.

The well-dressed man put out his cigarette on the dashboard of

the Mercedes, then told the one who was driving to stop. This is

good, here, he said. And shut off that infernal engine. He heard

the slide of the hand

brake, like a chain falling into a well. Then

4

nothing. It was as if the countryside had

been swallowed up

in

an unalterable silence.

It would

have been better to go straight there, said one of the

two sitting in back. Now he’ll

have time to run, he said. He had

a gun in his hand. He was only a boy. They called

him Tito.

He won’t run, said the well-dressed man. He’s had

it with

running. Let’s go.

Manuel

Roca moved aside some baskets of fruit, bent over,

raised a hidden trapdoor, and

looked

inside. It was little more

than a big hole dug into the earth, like the den of an animal.

“Listen to me, Nina. Now, some people are coming, and

I

don’t want them to see you. You have to hide in here, the best

thing is for you to hide in here and wait until they go away. Do

you understand?”

“Yes.”

“You just have to stay here and

be quiet.”

“ . . . ”

“Whatever happens, you mustn’t come out, you mustn’t

move, just stay here, be quiet, and wait.”

“ . . . ”

5

“Everything will

be all right.”

“Yes.”

“Listen to me. It’s possible I may have to go away with these

men. Don’t come out until your brother comes to get you, do

you understand? Or until you can tell that no one is there and

it’s all over.”

“Yes.”

“I want you to wait until there’s no one there.”

“ . . . ”

“Don’t be afraid, Nina, nothing’s going to happen to you. All

right?”

“Yes.”

“Give me a kiss.”

The girl

pressed

her lips against her father’s forehead. He

caressed

her hair.

“Everything will

be all right, Nina.”

He remained standing there, as if there were still something

he had to say, or do.

“This isn’t what I

intended,” he said. “Remember, always,

that this is not what I

intended.”

6

The child searched

instinctively in her father’s eyes for

something that might help

her understand. She saw nothing. Her

father leaned over and

kissed

her lips.

“Now go, Nina. Go on.”

The child

let herself fall

into the hole. The earth was hard and

dry. She lay down.

“Wait, take this.”

The father handed

her a blanket. She spread

it over the dirt

and

lay down again.

She heard

her father say something to her, then she saw the

trapdoor lowered. She closed

her eyes and opened them. Blades

of light filtered through the floorboards. She heard the voice of

her father as he went on speaking to her. She heard the sound of

the baskets dragged across the floor. It grew darker under there.

Her father asked

her something. She answered. She was lying on

one side. She had

bent her legs, and there she was, curled up, as

if in her bed, with nothing to do but go to sleep, and

dream. She

heard

her father say something else, gently, leaning down toward

the floor. Then she heard a shot, and the sound of a window

breaking into a thousand

pieces.

7

“ROCA! . . . COME OUT, ROCA

. . . DON’T

DO ANYTHING

STUPID, JUST

COME OUT.”

Manuel

Roca looked at his son. He crept toward the boy,

careful not to move into the open. He reached for the gun on the

table.

“Get away from there! Go and

hide in the woodshed. Don’t

come out, don’t make a sound, don’t do anything. Take the gun

and

keep

it loaded.”

The child stared at him without moving.

“Go on. Do what I tell you.”

But the child took a step toward

him.

Nina heard a hail of shots sweep the house, above her. Dust

and

bits of glass slid along the cracks in the floor. She didn’t

move. She heard a voice calling from outside.

“WELL, ROCA? DO WE HAVE TO COME AND GET YOU?

I’M TALKING

TO YOU, ROCA. DO I HAVE TO COME AND

GET YOU?”

The child was standing there, in the open. He had taken his

gun, but was holding it in one hand, pointing it down and

swinging it back and forth.

“Go,” said the father. “Did you hear me? Get out of here.”

8

The child went toward

him. What he was thinking was that

he would

kneel on the floor, and

be embraced

by his father. He

imagined something like that.

The father pointed the other gun at him. He spoke in a low,

fierce voice.

“Go, or I’ll

kill you myself.”

Nina heard that voice again.

“LAST

CHANCE, ROCA.”

Gunfire fanned the house, back and forth

like a pendulum, as

if it would never end, back and forth

like the beam of a

lighthouse over a coal-black sea, patiently.

Nina closed

her eyes. She flattened

herself against the blanket

and curled up even tighter, pulling her knees to her chest. She

liked

being in that position. She felt the earth, cool, under her

side, protecting her—it would not betray her. And she felt her

own curled-up

body, folded around

itself like a shell—she liked

this—she was shell and animal, her own shelter, she was

everything, she was everything for herself, nothing could

hurt her

as long as she remained

in this position. She reopened

her eyes,

and thought, Don’t move, you’re happy.

Manuel

Roca saw his son disappear behind the door. Then he

9

raised

himself just enough to glance out the window. All right, he

thought. He moved to another window, rose, quickly took aim,

and fired.

The man in the cream-colored suit cursed and threw himself

to the ground. Look at this bastard, he said. He shook

his head.

How about this son of a bitch? He heard two more shots from

the farmhouse. Then he heard the voice of Manuel

Roca.

“FUCK OFF, SALINAS.”

The man in the cream-colored suit spit. Go fuck yourself,

you bastard. He glanced to his right and saw that El

Gurre was

sneering, flattened

behind a stack of wood. He was holding a

machine gun in his right hand, and with

his left he searched

his

pocket for a cigarette. He didn’t seem to be in a hurry. He was

small and thin, he wore a dirty hat on his head and on his feet

enormous mountain clogs. He looked at Salinas. He found

the cigarette. He put it between his lips. Everyone called

him

El

Gurre. He got up and

began shooting.