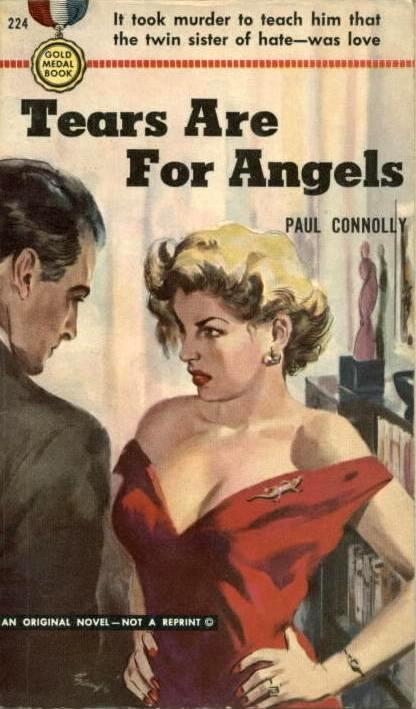

Tears Are for Angels

Read Tears Are for Angels Online

Authors: Paul Connolly

Tears Are for Angels

***

It took murder to teach him that the twin sister of hate-was love

…

A faithless wife.

A hated rival.

Murder!

The unwritten law.

Then Harry London set out to kill a man.

Along the path of vengeance he met another girl, another chance at love.

But he had to know hell before he knew the answer.

A new novel by Paul Connolly, author of

Get Out of Town

.

Get Out of Town

.

***

Scanning by unknown hero.

OCR, formatting & proofing by

P.

P.

***

CHAPTER ONE

I held the sights of the rifle steady on the can. My finger was just beginning the gentle squeeze on the trigger when the old car nosed over the low sand hill. It seemed to hesitate and then came on toward me.

It was a Chevrolet, maybe ten years old, dusty and nondescript, and I couldn't recall seeing it before. Not that many cars came over that hill.

I placed the rifle against the wall of the shack and picked up the fruit jar. It was not half empty yet, but when I put it down it was. I picked up the rifle again and leveled it on the can.

The car was barely moving now. Just as I squeezed the trigger, it came to a full stop. The can leaped on the stick and spun around, its stricken clang fading into the echoes of the shot.

"Nice shooting," the girl said.

I put the rifle down and picked up the jar again and watched her get out of the car. She wore slacks, and as she stepped slowly toward me she hooked her thumbs in the top of them the way a man would. I drank again.

"You're Harry London?"

It was a question, but the asking was not about the name. The words told me she knew I was Harry London. The question was merely a sort of unbelief that the man sitting there in the doorway of an unpainted shack, with a rifle leaning at his side and a fruit jar in his hand, could possibly be the person she already knew he was.

"What about it?" I said.

"They told me what I'd find," she said. "But I didn't believe it. Not till I saw you."

Some brief something that might once have been anger flickered around in my head. I grunted and set the jar down and picked the rifle up again. She was staring at me steadily with large brown eyes. She was a little older than Lucy had been, I decided; maybe twenty-six or twenty-eight. Not more, though, and probably not less.

"Is there anything around here I could sit on, maybe?"

I pointed at the ground, then lifted the rifle to my shoulder again. I hoped that this time the face would be on the can, but it wasn't. I fired anyway, and the can jumped and cried out again.

She was sitting on the ground when I lowered the rifle and I looked at her there, her legs Indian fashion under her, and then she laughed, her voice touched with harshness, her eyes on my left shoulder.

"That's a good trick for you, Harry. Do you ever miss it, just for the hell of it?"

I got up and went into the shack, taking the rifle and the fruit jar with me. I put the rifle in the corner and took a pull at the jar and lay down on the bunk and watched the rough ceiling, a little hazy now, and waited for the face. I tried to shut everything else out of my mind but the face wouldn't come, and then, without looking, I knew she was standing in the door, her thumbs hooked again in the top of the slacks.

"You don't fool me a damn bit," she said. "You're wondering what the hell I want with you, aren't you? And who I am?"

I didn't say anything and she came on into the room and stood over the bunk and looked down at me. Red lips curled in what might almost have been a smile.

"Look at you," she said. "Major Harry London. Gentleman farmer. That's what the papers called you. And now look. You even smell bad."

"Get out," I said.

"I will. When I get ready."

I grunted and let my arm fall toward the fruit jar. She stretched out a leg and nudged it out of reach. My fingers closed down on her ankle.

I hat hand was strong because it was the only one I had, and I squeezed hard. She made no sound, just standing there on one leg, swaying a little for balance.

"Hand that to me," I said.

"Go to hell."

I squeezed a little harder and she hopped a little on the one leg and then I began to see her, not as someone unwanted and intruding, but as a woman. She had close-cut blonde hair, a little wind-blown, and the large brown eyes were still unwavering, deep-set in her tanned face. The breasts rising under the loose T-shirt were not big like Lucy's, but they were high and pointed, and her hips were curved and the skin of the ankle under my fingers was smooth and cool.

I let the ankle go and swung my legs over the edge of the bed. I sat up and looked at her some more. Then I leaned down and picked up the jar. This time she didn't move.

"Get out," I said. "The hell with who you are. Just get out."

Her laugh was sharper.

"I might as well," she said. "But I want to tell you now. I have to laugh when I think about it, the way I felt when I read it."

"Read what?"

"About your wife. In the papers."

I put the jar down again, very carefully, and stood up. I reached out my arm and took hold of her shoulder and turned her around. But she twisted free and faced me again, her face angry now.

"I was looking for something else up in the library at Belleview. And then I read about it, in those old papers. It hit me funny, somehow. And I felt sorry for you. God, for you! You filthy, crazy old man!"

I slapped her hard and she quickly put a hand to her face and gave a little cry. I stepped forward and threw my arm about her waist and picked her up. I felt fists beat at my neck and face and I turned her around and threw her on the bunk and stood over her.

"Don't ever call me crazy," I said. "Not ever."

I think that right then was the only time I ever saw anything that even approached fear in her. She dug back a little into the shucks of the mattress and her hands were raised a little in front of her, her lips parted a little and her knees drawn up, and I guess maybe that faint, slight fear that flitted across her face was the only thing that saved her.

For suddenly it came to me out of what must have remained in me of shame that I stood over her with my one arm raised like a club, my teeth bared through the rank black beard growing from my neck and chin and jaws, my hair falling across my forehead. The tattered clothes I had not washed in weeks clung to my tall, gaunt frame. I reeked of corn whisky, not only on my breath but all over me, and the very air about me was charged with hate.

Then there was fear in me, too, fear of what I might have done, had tottered on the edge of doing. I turned away from her and my arm fell to my side and I went over and sat on the one chair in the room and watched her sit up on the bunk.

"You ought not to have come out here bothering me," I said.

She relaxed a little, and the fear went out of her face.

"I was so damn mad," she said. "It made me so damn mad to see what you'd done to yourself."

"Who are you?"

"I'm a writer. I free-lance for magazines and newspapers. That's why I was interested when I read about you and what your wife did in those old papers. I thought maybe I might be able to work out an article based on it. I thought it had a lot of human interest."

"I don't want anybody feeling sorry for me."

She laughed. "No, you don't," she said. "Then why are you doing this to yourself?"

"You'd better go," I said. "There's nothing here to write about."

"Don't worry. I'm going, all right." She reached down and rubbed her ankle.

"I'm sorry I hurt you," I said.

"Maybe I had it coming. I didn't know your whisky meant so much to you."

"But I'm not crazy. Don't ever think I'm crazy."

She put her head over on one side and looked at me.

"No," she said, "you're not crazy. By the way, do you ever take a bath, Harry?"

I stood up again. "All right, miss. That's enough."

She got up too and came over a little closer.

"It's still there," she said. "Shave off an acre or two of that beard, and peel a few layers of dirt off, and I guess it'd still be the face in the pictures, all right. Even the whisky can't take that jawline away. Only I guess it's not so strong as I thought it was."

I didn't say anything. She looked around her at the unswept floor and then bent over and picked up the fruit jar. She held it out to me, smiling, the brown eyes steady on mine.

"Grab it quick, Harry. I might drop it."

I took it from her and looked at it a moment and then pushed it slightly back at her.

"Have one yourself," I said, "before you go."

Because now I wanted her to stay. I wanted to talk to her and find out more about her.

Because one thing I was positive of: There hadn't been any newspaper pictures of me for her to see. Because I had read every paper that carried the story, searched them feverishly (or any between-the-lines meaning, and I knew none of them had run my picture. Lucy's, yes. But not mine.

There was puzzlement in her face now and she pushed her left hand through her hair quickly. She looked at the jar and then back at me.

"That's out of character," she said.

"I'm sorry. Living alone and all, I get pretty touchy."

"I guess you do. Thanks, but no, Harry. I don't think that stuff's for maiden throats."

"It's not so bad. The guy I get it from knows his business."

I held the jar out again and she took it. still puzzled, and I pushed the chair forward.

"Sit down. I'm sorry about all this. And now I'm trying to be nice."

She smiled then and it changed her face all over. It made me smile too, maybe the first time in two years I had smiled at anybody or anything.

She sat down and eyed the bottle and I went over to one of the shelves and poked around and found a glass that hadn't been used. I took the bottle back and poured one, not too stiff.

"There's a spring outside," I said. "I can get you a chaser."

"I'll chance it." She raised the glass to me. "Anything for a laugh," she said, and turned it up.

When she took the glass from her lips, she put it on the floor and leaned forward and began to pat herself on the chest. I laughed.

"I guess you have to get used to it," I said.

"Oh, no! Nobody could get used to that!"

I went over and sat down on the bunk and put the jar down between my legs.

"If you still think there's anything in it for you, Miss…?"

"Cummings. Jean Cummings."

"… Miss Cummings, you can write about me."

"I don't know," she said. "It hasn't got what I thought it might have, I'm afraid."

"What was that?"

"Well, my idea was to play the angle of what a man does after something like that happens to him. Inspirational sort of thing. How a guy makes a new life and all."

"Well, I made a new life," I said.

"You call this life?"

"Life is a lot of things. It depends on what you want out of it."

"And this is what you want?"

"Maybe it's all I can get."

"Hooey. You've still got everything you had in the beginning, only you just aren't using it."

"No," I said. "Not quite everything. An arm, for instance."

"So you lost an arm. And you've been hurt. Who hasn't been hurt? But most people don't just give up and go to pot."

"Most people have got two arms. And people that care about them."

"That's just self-pity."

I couldn't figure what was in her mind, but there had to be something. She was out here for something more than she had told me.

She stood up.

"I don't know why I'm giving you Bible stories," she said. "You must have had friends. You've heard all this before."

"That's right."

"Thanks for the… er, drink, anyway. I better beat it before I get your gander up again."

I stood up, too. There wasn't any way to keep her here if she wanted to go, and so far she had found out nothing except the way I lived, which was no secret. Maybe it was better to let her go now.

Other books

Acting on Impulse by Vega, Diana

Only for a Night (Lick) by Naima Simone

Sentinels of Fire by P. T. Deutermann

The One We Fell in Love With by Paige Toon

Drawn by Anderson, Lilliana

North of Nowhere by Steve Hamilton

Here Is a Human Being by Misha Angrist

What Love Sounds Like by Alissa Callen

Claire Delacroix by Pearl Beyond Price

A Darkness Forged in Fire by Chris (chris R.) Evans