With Love and Quiches (13 page)

Read With Love and Quiches Online

Authors: Susan Axelrod

After many marathon negotiating sessions, the lease

finally

got signed, and Irwin and I, our new landlord, and the lawyers from both sides all repaired to the legendary Algonquin Hotel for an after-midnight champagne supper. It was really that late, and we had earned it!

Actually, our new landlord reminded me a lot of my father. He had an opinion about everything, and he visited quite a bit more than he had to in order to check on our progress.

In the space of seven years, we had traveled from my kitchen, to my garage, to the little shop across from the firehouse, to our first commercial space in Oceanside, to our current home in Freeport. We were finally in a position to do some serious business. During this learning curve, we went from no dollars to just over $2.5 million—not too bad for a business that came from nowhere and started with nothing. We had put quiche on the map as an alternative to the hamburger, presenting it as a meal when accompanied by salad. Not quite Oreos, but still!

Incidentally, we found a tenant for the Oceanside facility because our lease was not yet up. We sublet it to the Knish Factory, run by a successful local kosher caterer. The man had been a friend of Irwin’s older brother, and Irwin always admired him because he was the only one of his brother’s friends who had a job. We sold him—and in some instances just left him—whatever equipment we would not be taking with us, including our rotary ovens, for $20,000 plus a $5,000 interest-free note due in five years. It was quite a bargain since the equipment we left behind was worth many times that. When the note came due, the tenant admitted he had been hopeful that we would have forgotten about it. Not likely. Anyway, he finally paid us.

I think that in the hope of continuing to attract some of our walk-in trade, he had done his street-front signage in the same colors and style as our Love and Quiches logo, calling it the Knish Factory instead of the Quiche Factory. Not

exactly

purposely, I don’t think; but even twenty years later, people would remark to us, “Hey, I just passed your place on Lawson Boulevard!”

Our move to Freeport was very different from the others. In prior years, we had financed whatever equipment we needed with proceeds from the business, but fitting out this plant properly would require some major financing. Unless self-financed, there is no way around this for any start-up or newly established business. My father had originally counseled me to develop a good relationship with a small local bank, and we did our original banking with Peninsula National Bank. They were taken over by the larger Norstar Bank, which was in turn absorbed by Fleet Bank. It was with Fleet Bank that we sought our financing.

Nothing

about the growth of my business came easily. The timing of this move coincided, with exquisite irony, with an unprecedented escalation of interest rates—just when we had borrowed serious money for the very first time.

During the recession of 1980, interest rates soared to 22 percent and higher, and we had projected, at most, 14 percent when seeking

our million dollars of plant financing. This spike affected us profoundly, our biggest challenge to date.

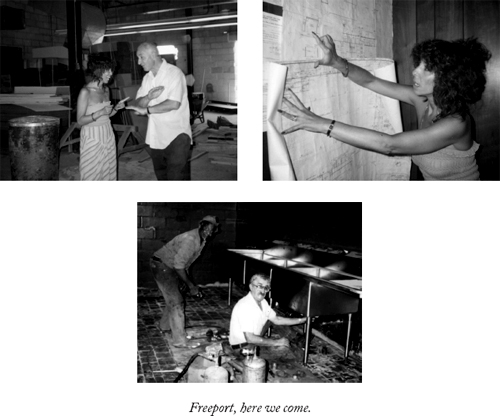

Here we were, about to enter the next phase of our journey. We had our first really detailed business plan, our architectural engineer on board, our professionals and equipment suppliers all drawing up the construction plans—yet these unprecedented interest rates were looming above us. It was too late to go backward. Moreover, I was determined to move forward and overcome the obstacles in my path even if it meant I had to sign away my life in the process.

We approached Fleet Bank with our financial plan, which included our intended floor plan, the equipment required, an operating budget, and our somewhat vague sales projections. Our accountant, who helped us prepare the plans, was the same one I had originally worked with when I was starting out, back in 1973. The projections were sound enough for the bank and we were granted our loan. We financed everything, both the construction and the equipment, through this one loan. And

everything

, including the spatulas and my house, was put up as collateral. Needless to say, betting more than you can afford to lose is an extremely dangerous gamble, but in this case I disobeyed my own rules. The total package amounted to about $1.2 million.

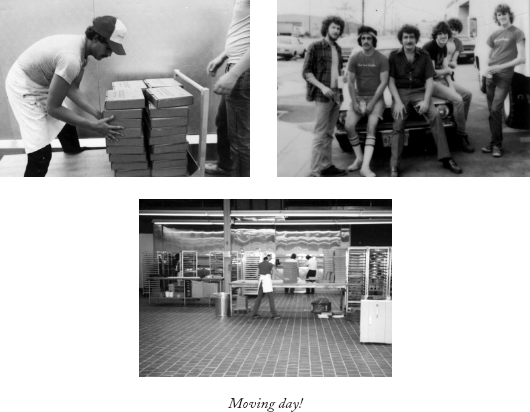

We took a deep breath and got started. We had the luxury of having our Oceanside facility fully operational until moving day, which fell on Labor Day weekend of 1980. We had no major equipment to take with us, since we left almost everything behind. All we had to move was our meager office furniture, a few 80- and 120-quart mixers, our pans, various racks, scales, storage bins, a few tables, and inventory of raw and finished goods. We accomplished most of this with our own trucks and the Love and Quiches Motley Crew; the rest went with a local moving company.

We had hired an architectural engineer to draw up the plans both for design of the workflow and to provide the City of Freeport with required blueprints: plumbing, electrical, etc. He also ran the job for us. Jay was

semiretired and elderly, but he possessed the energy of a twenty-year-old; we found him through a network of my father’s friends. He really knew what he was doing, and working with him provided me with one of the most memorable periods in my business career. He was amazing.

As you’ll recall from

chapter 5

, “The Mini-Factory (1976-1980)”, my father-in-law, a retired plumbing contractor, ran this part of the job—just as he had for the Oceanside mini-factory. Considerable electrical work was required, and for that we used a local independent electrician. He worked for the town by day and moonlighted our job by night. He was Italian and was constantly bragging to us about what a great cook his wife, Rose, was, so I gave her my pasta maker—since by then my home cooking days were pretty much over. We also hired a local flooring contractor to quarry-tile the six-thousand-square-foot production area. Our jack-of-all-trades, Willie the handyman, was around for odd jobs despite the fact that he really couldn’t paint.

The main heavy equipment—ovens, pan washer, refrigeration, and freezer—were built and installed by the manufacturers, as is customary, and training the employees on their use was included in the price. We had thought our eighteen- and twenty-four-pan rotary ovens in Oceanside were quite grand, but here we left them in the dust. We started out with two sixty-pan rotary ovens, then added two more, and finally added an eighty-pan oven as the years went by. Jay, our engineer, had included space in his designs for this type of expansion. We graduated to 140-quart, then 400-quart, and now much larger mixers and dough makers as well.

Yet we were still in some ways a do-it-yourself outfit. We recruited many of the Love and Quiches workers to help in the renovations, and they appreciated the overtime, besides wanting to be a part of it all. Both Jay and my father-in-law put my son Andrew and his friends to work, home as they were for the summer following their freshman year at Michigan State Hotel and Restaurant School. They performed a lot of the grunt work, just as son Irwin had done for his father when

he

was a teenager. I was one of the grunts, too. My mother-in-law was recruited to sit in the office all day throughout the summer to answer the one phone we had at the time. And

my

father hung around quite a lot, almost daily, as did our new landlord. They were enjoying themselves.

It was a long, hot summer. We all worked like horses; lots of “blood, sweat, and tears.” But by summer’s end, the renovations were completed, the equipment was up and running, and we were finally ready for the big move.

We accomplished the move in three days flat over the Labor Day weekend. All of our employees made the move to Freeport with us, and we were ready for business for the fall season of 1980, our busiest time of the year, by Tuesday morning with no disruptions.

Our new facility was so grand we were sure it would do very well until the end of time. We had

real

offices that were half the size of the entire Oceanside facility, an employee lounge, a separate retail shop (later converted into our test kitchen when we took some space across the street and moved the shop there), more than six thousand square feet of production space, a refrigerator bigger than our first house, and a freezer equal in size to the entire Oceanside mini-factory.

In fairly short order, however, six thousand square feet of production space became uncomfortably small. This was painfully evident when we needed to decorate our delicate Whipped Cream Cakes right next to the ovens, which generate a tremendous amount of heat. Sometimes the whole production area exceeded 100 degrees! Piping whipped cream rosettes and packing frozen cakes alongside the ovens was never fun. On some days, we provided the whole deco line with jackets and moved them into the refrigerator!

But on the plus side, with this move we also now had almost nine

thousand square feet for packing, shipping, and storage, a mechanics shop, and, finally, a loading dock.

And

, all of this with a water view!

Despite the advantages of the new space, our first year or so in Freeport was brutal. We were struggling with the reality of that 22-plus percent interest rate, floating about two points over prime, during this hyper-inflationary period. The bank had serious doubts that we could survive this economic debacle, and for a little while we had our

own

doubts. We started to secretly call our bank officer “Black Jack Fagan.” He was the prophet of doom and advised us either to give it all up and call it a day or to find a new bank. That, for me, was not an option. This very difficult period, among others that I will recount, almost took us down.

We found out pretty quickly that coming into this building with a bit less than $3 million in volume was simply not enough. We needed some quick growth, and happily, it started to come. I was on the road quite a bit, picking up more distributors in the tri-state area and beyond. Elaine started doing more outside sales too. We also moved one of our truck drivers, an original member of the Motley Crew, into local sales. Everybody agreed he was very “cute,” and he turned out to be very good at sales. He ended up running our local direct sales department, and later, after he married, his wife also joined Love and Quiches, working in distributor sales up and down the East Coast for many years. (We have never discouraged nepotism; in fact, it has

mostly

worked very well for us.)

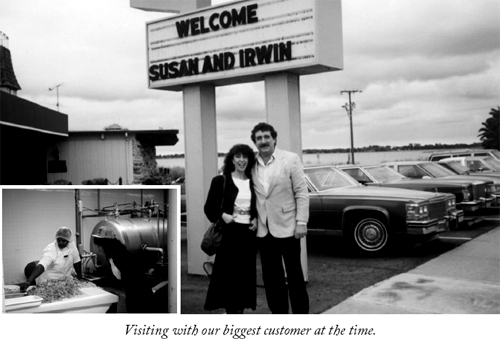

Most importantly, we still had our biggest customer: the restaurant chain that had ordered the six thousand cases of our Pecan Brownie Pie as a six-week special. Once it landed a place on their permanent menu, the Pecan Brownie Pie provided us with much-needed and steady volume, almost $1 million yearly, and that one account was instrumental in getting us through this trying period. Later, we provided products for other restaurant concepts the group developed and introduced. We had an excellent relationship with the buyers, and we were privileged to be invited to take a tour of their seafood processing plant on the west coast of Florida. It was fascinating, but much to our surprise, the workers peeling shrimp were paid by the piece, not by the hour.