With Love and Quiches (8 page)

Read With Love and Quiches Online

Authors: Susan Axelrod

We hadn’t defined our goals and we weren’t controlling our costs, buying well, or pricing our products properly. We paid no attention to vital details that virtually define success: we didn’t realize that pennies counted, and we didn’t know that we were also a service business and therefore had better provide good service along with our products. By now we should have been polishing our image, but instead we had remained in our original mindset: clueless.

The wholesale food processing business, as with any business involving production and service, is a full-time commitment, especially when there is established competition. It takes a tremendous amount of work, and we weren’t good enough. We had started losing accounts at about the same rate as we were getting them because our service wasn’t very good and our quality was uneven. The taste was there, but as I pointed out earlier, the weights were anybody’s guess.

Our problems were those often faced by small businesses: we lacked capital, we lacked management and technical assistance, and we had

no formal technical training in our particular field. We had no understanding of finance, and we were inexperienced about marketing and buying opportunities. In sum, we

still

had no preparation whatsoever for business ownership, which put us at a great disadvantage.

Now what? I found myself alone in the enterprise. It was a lonely feeling at first, but exciting too. There were a lot of possibilities ahead, and I wanted to stick around to see how the story ended. I was

way

out of my comfort zone, but I had bought my own business, and I had to assess what I had bought. I knew I might be in for the ride of my life, along with plenty of potential heartbreak—yet, at the very least, I wanted some payback for all of the burns I had suffered up and down my arms.

We were a young married couple with two children, a big house, and very little money. Yet, this recessionary period during which we rolled our first dough provided Love and Quiches with its start; we saw the rise of the pub without a pastry chef. This became my motivator.

With Jill gone and a few rudimentary business lessons under my belt, I knew I needed to turn things around. This is the point at which I launched the real business. I stopped dead in my tracks and made a fresh beginning. The very first step I took was to create an informal business plan. I outlined the scope of my operation: what I hoped to achieve, and what I needed to do. A more formal plan followed, detailing both the big picture and the smaller ones. This more formal plan detailed my rudimentary strategy and tentative marketing plans. I realized that even without Jill I could rely on a strong network for help: I had my accountant, my family, my friends, my mentor Marvin Paige, and anybody else I could get my hands on to answer my questions. I was learning fast and furiously.

The one constant of my endeavor was my own ability to sell. I had to develop an organization that could meet the demands created by my sales out front. This was true even in that first small shop on Franklin Avenue where we were operating. I was virtually starting again. I had so very much to accomplish in a dozen areas, and I had to do it right

away or I would lose the momentum we had most definitely created but could not control.

I knew I had to gather the cash to get me through the next year or two, until I could develop a positive cash flow. (Yes, I finally knew what the term “cash flow” meant!) And I simply knew, with innocent clarity, that I wasn’t going to

allow

myself to fail. I broke a lot of my own rules along the way, but I did what I had to do. I’m still here.

I was also mindful not to invest more than I could afford to lose, however little that was, just in case I was wrong and couldn’t pull it off. And unlike Jill’s and my initial mindless ideas, I would be doing it for the

money,

not the

glory

, which could carry me just so far.

Even though I was still using handwritten index cards, I now knew my formulas and all my costs. I borrowed $15,000 from my father (the only time he directly helped me financially) to give me some breathing room, and little by little, I righted the ship. My capital limited my participation in the marketplace. I developed the ability to know those limits and to rely on my budget. And then my business did begin to grow, and then to grow again.

I was working twelve- to fourteen-hour days, but I was thinking and planning all 24/7. I had my one or two employees and Don, my driver, who would pitch in with production when he wasn’t on the road. Soon after Jill left, Bridget started coming with me to work in the shop almost every day, just as she had done when we ran Bonne Femme in the garage. But now she wanted to know when “we” were going to get someone in to clean the house!

In spite of all this, there

was

a home front, and I needed to keep at least a semblance of order while all this was going on. I will discuss how we kept it all together later in my narrative, in

chapter 17

, “Family Matters.”

At this point I was still the baker, salesman, and chief bottle washer; yet the business by mid-1975 had grown to well over $100,000 per year in volume. Our reputation came through the turmoil of my partnership breakup intact; our products were still delicious; and, more

importantly, they were always consistent. I was now able to breathe a little easier and have some fun, too.

Then someone new walked into my life, and everything changed again.

Shortly after Jill left the business, an acquaintance of mine called me to ask if I would be interested in meeting the husband of her housekeeper, who was a trained baker. The husband, James Gilliam, was out of work due to an injury, but he was looking for something he could do for a few hours a week. It was this chance introduction that brought the man who was to become Love and Quiches’ head baker into the fold.

Jimmy the Baker, as he will be called from here on in the book, was a black man who got his professional training in the navy. At the time, a man of color, at least in civilian life, was not often given the chance to be considered a head baker. We were still in the mid-seventies, and this was the reality, even if it was the North. Instead, bakeries had employed Jimmy merely as a benchman. Yet I was told by many of my suppliers during those early years that Jimmy always

ran

the local bakeries in which he worked. He was a legend in the regional bakery industry.

Jimmy came to work for me in 1975, and I found out very quickly that old-fashioned bakers are strictly nocturnal beings. He worked only at night, dressed in his crisp whites, no matter how hard I tried to convince him otherwise. I soon got used to arriving in the morning to find all the day’s production completed and perfect. Gone were the days of tissue-thin cheesecakes! We still were making the quiches during the day, but Jimmy took on all the desserts. Now I was able to introduce a variety of layer cakes from Jimmy’s recipes, chocolate and carrot to start, then a few others, in this tiny shop.

Jimmy was also a superb bread baker. And although we have never sold any yeast products commercially, just to keep in practice he often

baked a few racks of the most wonderful French breads—including, sometimes, brioche—for the staff. We devoured it all, slathered in butter, within minutes of starting our day. I was always reminded of Evelina and

her

bread when Jimmy treated us to

his

bread.

Jimmy was stubborn and had a quick temper, but everybody loved him. He was all business, but he had a soft side if you sought it out. He lived a few towns over, and his house was by far the most well kept on the block, with not a twig out of place. This is the same way he handled everything in our little shop. When I arrived in the morning, everything was sparkling, and, if he had not already left for the day, I was always amazed to see that he had not a drop of chocolate on his crisp whites.

By mid-1976 I knew a lot more about running a business, and with Jimmy’s help, experience, and knowledge, we were really moving ahead. Love and Quiches was doing several hundreds of thousands of dollars in volume and generating a profit for the first time in its short history!

We were gaining ground every week in our little storefront. Jimmy the Baker was turning out gorgeous desserts every night, our sizes and varieties of quiche were growing a little, and Don was maturing by the minute, taking on some management responsibilities inside the shop in addition to making deliveries a bit farther afield, from Staten Island to Brooklyn to Long Island and every place in between. Also by mid-1976, we had about seven or eight full-time employees (one or two of whom would stay with us for decades).

Our roster of customers continued to grow, though we were still a local supplier doing “store door” deliveries in our own trucks. We had no distributors yet; I’m not sure I even knew then what a distributor could actually do for me. We still had most of our original customers—including our first, the Windmill—but we now had many more

in

the city, where I had concentrated my sales efforts. One of our newer customers right in Manhattan was a café opened by “society” restaurateur George Lang in the new Citicorp building. George was also the

proprietor of the venerable Café Des Artistes (which has only recently closed), and his lavish apartment was famous for its spectacular green jade bathtub. George moved in rarified circles, but it didn’t stop him from beating me out of $1,700 in receivables when they folded the Citicorp Café. I was outraged, but when I protested, my only answer from his management was, “Grow up, girlie!” This turned out to be a fairly cheap education, because since then we have kept a very tight rein on our receivables.

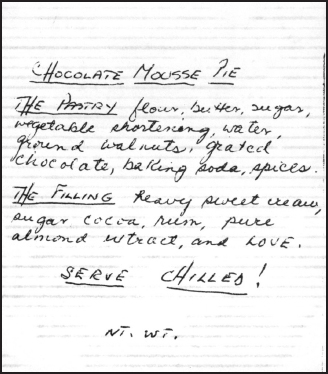

We were also polishing up our image with sturdier packaging and more professional labeling. The resultant improved handling provided savings in labor and also eliminated waste. We moved to printed ingredient labels, eliminating our rather childish practice of filling out our labels by hand, running them off on a copier at a local stationery shop with ink that smudged and ran, and then cutting them out one by one. How ridiculous was that? Turned out that our hand-cut labels cost us more than our new printed ones once you counted in the labor, which we were finally beginning to do.

We retired the Silver Bullet and bought our first real freezer truck. It was hot pink this time, and printed on its side in professionally drawn white letters were our address, our telephone numbers, and our newly stylized logo. We had appropriated the lady with the rolling pin (part of our logo until recently) from an image my college roommate found for me in a children’s coloring book. Trucks are great “vehicles” for advertising! Losing my homespun style and image gave me further entrée into some larger foodservice organizations.

Once again, something accidental that proved pivotal precipitated our move to our first industrial space. On January 17, 1976, Jill was written up in a human interest story by the

New York Times

. It was an article about a woman who had started a business from scratch but decided to leave it, returning home to find a much smaller enterprise in which she could control her time, rather than the other way around.

From that

Times

article I received a phone call from the foodser-vice director at Columbia University. Columbia did a tremendous amount of catering and became a very large customer of ours. As was often the case with my customers, the director and I also became good friends for many years, until he moved out of the state after accepting another position.

The article also attracted the attention of the buyer who ran the restaurants in Bamberger’s department stores, later bought and absorbed into Macy’s. This was my first large multiunit account; the company had fourteen stores from the New York metro area all the way down to Maryland. For the first few months, my patient and supportive husband made the delivery run (fourteen hours!) in our shiny new truck once every other week, until the buyer put us together with his meat and produce supplier. This supplier became our very first distributor and “delivered” Irwin from his grueling ordeal!

Just as Bonne Femme had in my garage, Love and Quiches was straining at the seams. Stuff was piled up everywhere, there was no

room for much-needed new equipment, and we had no real bakery ovens. Far worse, there wasn’t nearly as much freezer storage as we now needed in the wake of the article—and we were, after all, a frozen foods business! Although this little storefront in Hewlett had served us well, I knew I wouldn’t miss the cluttered place for a second. We were at the end of our rope, and I knew we had to get out of there—and fast!

The Mini-Factory (1976–1980)

Whenever you take a step forward, you are bound to disturb something.

—Indira Gandhi

I

didn’t want to move far, no more than five or ten minutes from home. Irwin, always ready to help me, was my sidekick in my search for new space. We started by driving in small concentric circles around the Hewlett location in our Chevy, zeroing in on commercial areas in nearby towns. One day we were cruising around Oceanside, two towns over and about ten minutes from our shop, when we noticed a For Rent sign that looked promising. It stood in front of a neat-looking one-story building with a brick façade. Though the building had no loading dock, it did have a wide garage door that would allow our truck to back up close to load up in the mornings. The building was on a wide boulevard, a main route to all the beaches—including Jones Beach—and we realized that this spot,

if it worked out, would help us pick up a lot more retail walk-ins even as we kept our current customers, since it was so close to the old space. It was perfect!