Wired for Love (8 page)

Authors: Stan Tatkin

Neither Leia nor Franklin was able to step into the other’s shoes, or simultaneously value and reckon with both points of view. Leia, for example, was so wrapped up in her own needs and desires that she didn’t stop to consider the stresses and fears Franklin might be feeling. It didn’t occur to her to ask what he was feeling, or to show appreciation for the fact that he might also be upset, for his own reasons. She simply expected him to conform to her views of the situation.

This basic inability to empathize may point to a poorly developed orbitofrontal cortex. Leia’s orbitofrontal cortex could have been temporarily offline due to threat, and therefore unable to appreciate anything beyond her own ideas and feelings. Or it could have been disabled due to drug abuse or other medical reasons. Or perhaps, due to experiences during childhood, it never fully developed, making it difficult for her to empathize with and understand a partner’s views and perspectives. In that case, even if she had another partner who was less reactive than Franklin, her orbitofrontal cortex would be no better equipped.

As long as Leia and Franklin—one or both—are unable to see, understand, and appreciate their partner’s concerns or viewpoint, they will not be able to create a couple bubble. It will be difficult if not impossible for them to keep their love alive. However, if Leia’s and Franklin’s orbitofrontal cortices can operate properly, they will rein in their amygdalas and hypothalami at critical moments. Their smart vagi will remain engaged, and their right and left brains will act out of friendliness.

One solution to the problem of an offline orbitofrontal cortex is for partners to wait until they have calmed down enough to be able to make even the slightest gesture to help one another. Learning to remember to summon the help of the smart vagus and take a few deep breaths can help. Then, for instance, with even a modicum of calm, Franklin could have led with a sign of friendliness by saying something like “Honey, I love you and I understand where you’re coming from. You’re worried I’ll never ask you to marry me. I understand, and I don’t blame you for worrying.” Such an act of friendliness and love disarms the primitives enough to enable the ambassadors to begin to come back online. As soon as Franklin senses their return, he can follow up with an appeal to Leia’s ambassadors.

Most if not all of the recommendations in this book rest on the principle that you, as partners, need one another to keep love and avoid war. Initially, it can take time and some false starts. But eventually both of you must learn how to do this in a snap, without too much thought or talk. And that’s easier, as we will see in the next chapter, if you have an owner’s manual that includes instructions on what to do, and when, with your partner.

Exercise: Primitives, Meet Your Ambassadors

You can practice this exercise with your partner.

Allow your primitives and ambassadors to hold a dialogue. Do this in the spirit of a parlor game, rather than as a means to solve a pressing relationship problem. The point is to become better acquainted with your primitives and ambassadors, to learn to recognize their respective voices. Of course, if important issues come up in the process, that’s fine too.

Try any or all of the following combinations:

- Have your primitives talk to your partner’s primitives.

- Have your primitives talk to your partner’s ambassadors.

- Have your ambassadors talk to your partner’s primitives.

- Have your ambassadors talk to your partner’s ambassadors.

You might also try having your right brain interact with your partner’s right brain. Then have your left brain interact with your partner’s left brain. And then switch it up.

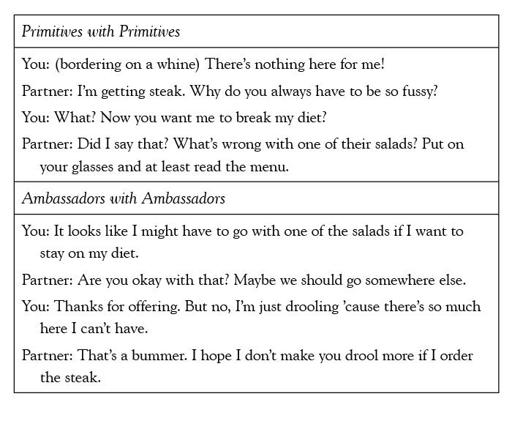

Examples of situations you might use include selecting from a menu at a restaurant (table 2.3), taking the dog for a walk, hanging a picture in the living room.

Table 2.3 Sample Dialogues: What’s on the Menu?

What differences do you notice between the various interactions? As you become more familiar with the voices of your own and your partner’s primitives and ambassadors, you can try this exercise with more significant topics.

Second Guiding Principle

The second principle of this book is that

partners can make love and avoid war when their primitives are put at ease.

In this chapter, we have taken a journey through the brain, so to speak, to familiarize you with those aspects that are wired for war and those wired for love. Getting a sense of how these aspects work in your relationship is the first step in keeping love alive.

In the meantime, here are some supporting principles to guide you:

- Identifying your primitives in action helps to hold them in check. Now that you know who your primitives are and how they operate, see if you can catch them in the act. When a red alert is going off, for example, can you recognize it for what it is? I’m not suggesting you will automatically know how to instantly turn it off. First simply recognize that your amygdalae are sounding an alarm. This alarm may take the form of your heart racing, palms sweating, face burning, or muscles tightening, or you may notice yourself suddenly becoming weak, slouched, nauseous, faint, numb, or shut down. In later chapters, I will discuss more specific techniques you and your partner can use when your primitives are running the show.

Of course, identifying your primitives can be accomplished only by none other than…your ambassadors; specifically, your hippocampus. By definition, if you are able to notice your primitives in action, they can’t have gained the upper hand. If they have, it’s too late; better luck next time. And you can be assured that there most likely will be a next time.

- It’s always helpful to recognize what works well, in addition to what does not. For this reason, I also recommend identifying your ambassadors. Notice when they step up to the plate in support of your relationship; give them credit where credit is due. And invite them to step forward whenever their warmth, wisdom, and calm are needed.

If your primitives are allowed to have their way—as sometimes happens—there will be no lollygagging around when danger’s afoot. Life will be filled with one crisis after another, as you continually fire blind without thinking of the consequences. But when relationships are at stake, you want to avoid pulling the trigger. So call on your ambassadors to slow things down.

- Identify your partner’s primitives and ambassadors in action. At times, especially if your partner’s primitives are large and in charge, you may be able to do this before your partner can. Likewise, your partner sometimes may be able to do it for you before you can yourself. Find nonthreatening ways to let each other know what you have noticed. If possible, do this as close in time as you can to the actual incident.

Learning to recognize your partner’s primitives and ambassadors gives you both a tool with which to better understand one another. This understanding is one important ingredient of a couple bubble. In the next chapter, we’ll look more closely at what it means to really know your partner.

Chapter 3

Know Your Partner: How Does He or She Really Work?

Who are we as relationship partners? How do we move toward and away from (both literally and figuratively) those upon whom we depend? It always amazes me that couples can be together for fifteen, twenty, even thirty years and the partners still feel they don’t know each other. In so many ways, they don’t know what makes each other tick.

As we saw in chapter 2, becoming acquainted with our primitives and ambassadors helps us answer these questions to some extent. But not everyone responds the same way in a relationship. The balance of power within and between the primitive and ambassador camps differs from person to person. Not everyone’s ambassadors, for example, can rein in their primitives equally fast. In fact, due to the variance in your brains, you and your partner may experience different interactions between your primitives and ambassadors.

So, we each come to the table oriented toward a certain style of relating. We may recognize our partner’s style, but often it is not on a conscious level. Unhappy partners often claim ignorance (“If I knew you were like this, I’d never have married you”) and maintain claims of ignorance (“I just don’t know what planet you’re on”) throughout the relationship. In this chapter, we explore why this mystification can occur, and what you can do to overcome it in your relationship.

As a couple therapist, I have come to know that such claims of ignorance are essentially untrue, even though they may feel true to the people who say them. They are untrue because we all have a style of relating that remains quite stable over time. Growing up, our parents’ or caregivers’ styles of relating set the standard by which we learned to adapt. Simply put, as we saw in chapter 2, our social wiring is set at an early age. Despite our intelligence and exposure to new ideas, this wiring remains virtually unchanged as we age. For instance, I commonly hear new parents say, “I will never do what my parents did to me,” and yet despite their most ardent wishes not to repeat their parents’ mistakes, in periods of distress they do exactly that. I don’t say this with judgment; it’s just a matter of human nature and biology.

Most partners audition for relationships fully unaware of who they are and how they are wired to relate in a committed couple universe. As in all auditions, they endeavor to put themselves forward in the best light. It wouldn’t make sense for someone on the first date to say, “I spent a lot of time alone as a kid and I still do. I don’t like my alone time to be intruded upon. I’ll come to you when I’m ready. And don’t bother coming to me, because then I’ll think you’re demanding something of me, and I don’t like that.” An equally quick way to send a date running for the hills would be to say, “I tend to be clingy, and to get angry when I feel abandoned. I hate silences and being ignored. I never seem to get enough from people, yet I don’t take compliments well because I don’t believe people are being sincere, so I tend to reject anything nice.” During the initial phase of a relationship, partners may give clues about their basic predilections with regard to physical proximity, emotional intimacy, and concerns regarding safety and security. But it is only when the relationship becomes permanent in either or both partners’ mind that these predilections really come to life.

Much of what we do, we do automatically and without thinking. This is largely the work of our primitives. In relationships, one of the things partners typically are unaware of is how they physically move toward and away from each other. Our brain’s reaction to physical proximity and duration of proximity is wired from early childhood, and influences such things as where we choose to stand or sit in relation to one another, how we adjust distance between us, how we embrace, how we make love, and just about everything we do that involves physical movement and static physical space. Because we operate largely on automatic pilot, we remain oblivious to this entire dimension of our interactions. Moreover, we handle physical proximity differently during courtship than in more committed phases of relationship. For example, many couples touch constantly while they’re dating, but the frequency with which they touch drops off dramatically after they make a commitment. This can be very confusing, and can lead partners to wonder, “Do I even know who you are anymore?”

“Who Are You?”

No one likes to be classified, yet we tend to classify the people and things around us because we have brains that, by nature, organize, sort, and compare information and experience. In fact, people have been defining the human condition for centuries, and they continue to form new ways of doing so today. We are liberals or conservatives, geeks or Goths, atheists or religious fanatics, Scorpios or Capricorns, either from Mars or from Venus. As long as we don’t use these categories to debase or dehumanize anyone, they can help us understand one another.

A key premise of this book is that partners can benefit from having an owner’s manual for one another and for their relationship. An important function of this manual is that it allows you to define, describe, and ultimately label your partner’s predilections and relationship style. If you can recognize and understand each other’s styles, it is much easier to work together and to resolve issues as they arise. Having the sense that “I know who you are” makes it easier to be forgiving and to be sincerely supportive.

The styles I present here are neither new nor entirely my own. They are drawn from research findings, first made popular by John Bowlby (1969) and Mary Ainsworth and her colleagues (Ainsworth, Bell, and Stayton 1971) almost half a century ago, explaining how infants form attachments. Over the years, I have observed that most partners fall into one of three main relationship styles. I offer these styles to you with a couple of caveats.