William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition (8 page)

Read William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition Online

Authors: William Shakespeare

Tags: #Drama, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare

BOOK: William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition

3.46Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In all but one of Shakespeare’s plays the revisions are local—changes in the wording of individual phrases and lines—or else they are effected by additions and cuts. Essentially, then, the story line is not affected. But in

King Lear

the differences between the two texts are more radical. It is not simply that the 1608 quarto lacks over 100 lines that are in the Folio, or that the Folio lacks close on 300 lines that are in the Quarto, or that there are over 850 verbal variants, or that several speeches are assigned to different speakers. It is rather that the sum total of these differences amounts, in this play, to a substantial shift in the presentation and interpretation of the underlying action. The differences are particularly apparent in the military action of the last two acts. We believe, in short, that there are two distinct plays of

King

Lear, not merely two different texts of the same play; so we print edited versions of both the Quarto (

‘The History of

...’) and the Folio (‘

The Tragedy of

...’).

King Lear

the differences between the two texts are more radical. It is not simply that the 1608 quarto lacks over 100 lines that are in the Folio, or that the Folio lacks close on 300 lines that are in the Quarto, or that there are over 850 verbal variants, or that several speeches are assigned to different speakers. It is rather that the sum total of these differences amounts, in this play, to a substantial shift in the presentation and interpretation of the underlying action. The differences are particularly apparent in the military action of the last two acts. We believe, in short, that there are two distinct plays of

King

Lear, not merely two different texts of the same play; so we print edited versions of both the Quarto (

‘The History of

...’) and the Folio (‘

The Tragedy of

...’).

Though the editor’s selection, when choice is available, of the edition that should form the basis of the edited text is fundamentally important, many other tasks remain. Elizabethan printers could do meticulously scholarly work, but they rarely expended their best efforts on plays, which—at least in quarto format—they treated as ephemeral publications. Moreover, dramatic manuscripts and heavily annotated quartos must have set them difficult problems. Scribal transcripts would have been easier for the printer, but scribes were themselves liable to introduce error in copying difficult manuscripts, and also had a habit of sophisticating what they copied—for example, by expanding colloquial contractions—in ways that would distort the dramatist’s intentions. On the whole, the Folio is a rather well-printed volume; there are not a great many obvious misprints; but for all that, corruption is often discernible. A few quartos—notably A

Midsummer Night’s Dream

(1600)—are exceptionally well printed, but others, such as the 1604

Hamlet,

abound in obvious error, which is a sure sign that they also commit hidden corruptions. Generations of editors have tried to correct the texts; but possible corruptions are still being identified, and new attempts at correction are often made. The preparation of this edition has required a minutely detailed examination of the early texts. At many points we have adopted emendations suggested by previous editors; at other points we offer original readings; and occasionally we revert to the original text at points where it has often been emended.

Midsummer Night’s Dream

(1600)—are exceptionally well printed, but others, such as the 1604

Hamlet,

abound in obvious error, which is a sure sign that they also commit hidden corruptions. Generations of editors have tried to correct the texts; but possible corruptions are still being identified, and new attempts at correction are often made. The preparation of this edition has required a minutely detailed examination of the early texts. At many points we have adopted emendations suggested by previous editors; at other points we offer original readings; and occasionally we revert to the original text at points where it has often been emended.

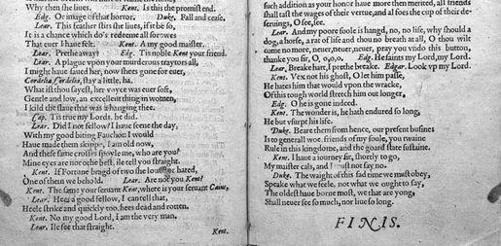

12. The last lines of King Lear in the 1608 quarto

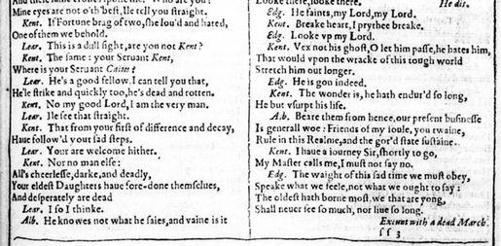

13. The last lines of King Lear in the 1623 First Folio

Stage directions are a special problem, especially in a one-volume edition where some degree of uniformity may be thought desirable. The early editions are often deficient in directions for essential action, even in such basic matters as when characters enter and when they depart. Again, generations of editors have tried to supply such deficiencies, not always systematically. We try to remedy the deficiencies, always bearing in mind the conditions of Shakespeare’s stage. At many points the requisite action is apparent from the dialogue; at other points precisely what should happen, or the precise point at which it should happen, is in doubt—and, perhaps, was never clearly determined even by the author. In our edition we use broken brackets—e.g. [

He kneels

]—to identify dubious action or placing. Inevitably, this is to some extent a matter of individual interpretation; and, of course, modern directors may, and do, often depart freely from the original directions, both explicit and implicit. Our original-spelling edition, while including the added directions, stays somewhat closer to the wording of the original editions than our modern-spelling edition. Readers interested in the precise directions of the original texts on which ours are based will find them reprinted in

William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion.

He kneels

]—to identify dubious action or placing. Inevitably, this is to some extent a matter of individual interpretation; and, of course, modern directors may, and do, often depart freely from the original directions, both explicit and implicit. Our original-spelling edition, while including the added directions, stays somewhat closer to the wording of the original editions than our modern-spelling edition. Readers interested in the precise directions of the original texts on which ours are based will find them reprinted in

William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion.

Ever since Shakespeare’s plays began to be reprinted, their spelling and punctuation have been modernized. Often, however, this task has been left to the printer; many editors who have undertaken it themselves have merely marked up earlier edited texts, producing a palimpsest; there has been little discussion of the principles involved; and editors have been even less systematic in this area than in that of stage directions. Modernizing the spelling of earlier periods is not the simple business it may appear. Some words are easily handled: ‘doe’ becomes ‘do’, ‘I’ meaning ‘yes’ becomes ‘ay’, ‘beutie’ becomes ‘beauty’, and so on. But it is not always easy to distinguish between variant spellings and variant forms. It is not our aim to modernize Shakespeare’s language: we do not change ‘ay’ to ‘yes’, ‘ye’ to ‘you’, ‘eyne’ to ‘eyes’, or ‘hath’ to ‘has’; we retain obsolete inflections and prefixes. We aim not to make changes that would affect the metre of verse: when the early editions mark an elision—know‘st’, ‘ha’not’, ‘i’th’temple‘—we do so, too; when scansion requires that an -ed ending be sounded, contrary to modern usage, we mark it with a grave accent—formed’, ‘moved’. Older forms of words are often preserved when they are required for metre, rhyme, word-play, or characterization. But we do not retain old spellings simply because they may provide a clue to the way words were pronounced by some people in Shakespeare’s time, because such clues may be misleading (we know, for instance, that ‘boil’ was often pronounced as ‘bile’, ‘Rome’ as ‘room’, and ‘person’ as ‘person’), and, more importantly, because many words which we spell in the same way as the Elizabethans have changed pronunciation in the mean time; it seems pointless to offer in a generally modern context a mere selection of spellings that may convey some of the varied pronunciations available in Shakespeare’s time. Many words existed in indifferently variant spellings; we have sometimes preferred the more modern spelling, especially when the older one might mislead: thus, we spell ‘beholden’, not ‘beholding’, ‘distraught’ (when appropriate), not ‘distract’.

Similar principles are applied to proper names: it is, for instance, meaningless to preserve the Folio’s ‘Petruchio’ when this is clearly intended to represent the old (as well as the modern) pronunciation of the Italian name ‘Petruccio’; failure to modernize adequately here results even in the theatre in the mistaken pedantry of ‘Pet-rook-io’. For some words, the arguments for and against modernization are finely balanced. The generally French setting of

As You Like It

has led us to prefer ‘Ardenne’ to the more familiar ‘Arden’, though we would not argue that geographical consistency is Shakespeare’s strongest point. Problematic too is the military rank of ensign; this appears in early texts of Shakespeare as ‘ancient’ (or ‘aunciant’, ‘auncient’, ‘auntient’, etc.). ‘Ancient’ in this sense, in its various forms, was originally a corruption of ‘ensign’, and from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries the forms were interchangeable. Shakespeare himself may well have used both. There is no question that the sense conveyed by modern ‘ensign’ is overwhelmingly dominant in Shakespeare’s designation of Iago (in

Othello)

and Pistol (in 2

Henry IV, Henry V

, and

The Merry Wives of Windsor

), and it is equally clear that ‘ancient’ could be seriously misleading, so we prefer ‘ensign’. This is contrary to the editorial tradition, but a parallel is afforded by the noun ‘dolphin’, which is the regular spelling in Shakespearian texts for the French ‘dauphin’. Here tradition favours ‘dauphin’, although it did not become common in English until the later seventeenth century. It would be as misleading to imply that Iago and Pistol were ancient as that the Dauphin of France was an aquatic mammal.

As You Like It

has led us to prefer ‘Ardenne’ to the more familiar ‘Arden’, though we would not argue that geographical consistency is Shakespeare’s strongest point. Problematic too is the military rank of ensign; this appears in early texts of Shakespeare as ‘ancient’ (or ‘aunciant’, ‘auncient’, ‘auntient’, etc.). ‘Ancient’ in this sense, in its various forms, was originally a corruption of ‘ensign’, and from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries the forms were interchangeable. Shakespeare himself may well have used both. There is no question that the sense conveyed by modern ‘ensign’ is overwhelmingly dominant in Shakespeare’s designation of Iago (in

Othello)

and Pistol (in 2

Henry IV, Henry V

, and

The Merry Wives of Windsor

), and it is equally clear that ‘ancient’ could be seriously misleading, so we prefer ‘ensign’. This is contrary to the editorial tradition, but a parallel is afforded by the noun ‘dolphin’, which is the regular spelling in Shakespearian texts for the French ‘dauphin’. Here tradition favours ‘dauphin’, although it did not become common in English until the later seventeenth century. It would be as misleading to imply that Iago and Pistol were ancient as that the Dauphin of France was an aquatic mammal.

Punctuation, too, poses problems. Judging by most of the early, ‘good’ quartos as well as the section of

Sir Thomas More

believed to be by Shakespeare, he himself punctuated lightly. The syntax of his time was in any case more fluid than ours; the imposition upon it of a precisely grammatical system of punctuation reduces ambiguity and imposes definition upon indefinition. But Elizabethan scribes and printers seem to have regarded punctuation as their prerogative; thus, the 1600 quarto of A

Midsummer Night’s Dream

is far more precisely punctuated than any Shakespearian manuscript is likely to have been; and Ralph Crane clearly imposed his own system upon the texts he transcribed. So it is impossible to put much faith in the punctuation of the early texts. Additionally, their system is often ambiguous: the question mark could signal an exclamation, and parentheses were idiosyncratically employed. Modern editors, then, may justifiably replace the varying, often conflicting systems of the early texts by one which attempts to convey their sense to the modern reader. Working entirely from the early texts, we have tried to use comparatively light pointing which will not impose certain nuances upon the text at the expense of others. Readers interested in the punctuation of the original texts will find it reproduced with minimal alteration in our original-spelling edition.

Sir Thomas More

believed to be by Shakespeare, he himself punctuated lightly. The syntax of his time was in any case more fluid than ours; the imposition upon it of a precisely grammatical system of punctuation reduces ambiguity and imposes definition upon indefinition. But Elizabethan scribes and printers seem to have regarded punctuation as their prerogative; thus, the 1600 quarto of A

Midsummer Night’s Dream

is far more precisely punctuated than any Shakespearian manuscript is likely to have been; and Ralph Crane clearly imposed his own system upon the texts he transcribed. So it is impossible to put much faith in the punctuation of the early texts. Additionally, their system is often ambiguous: the question mark could signal an exclamation, and parentheses were idiosyncratically employed. Modern editors, then, may justifiably replace the varying, often conflicting systems of the early texts by one which attempts to convey their sense to the modern reader. Working entirely from the early texts, we have tried to use comparatively light pointing which will not impose certain nuances upon the text at the expense of others. Readers interested in the punctuation of the original texts will find it reproduced with minimal alteration in our original-spelling edition.

Theatre is an endlessly fluid medium. Each performance of a play is unique, differing from others in pace, movement, gesture, audience response, and even—because of the fallibility of human memory—in the words spoken. It is likely too that in Shakespeare’s time, as in ours, changes in the texts of plays were consciously made to suit varying circumstances: the characteristics of particular actors, the place in which the play was performed, the anticipated reactions of his audience, and so on. The circumstances by which Shakespeare’s plays have been transmitted to us mean that it is impossible to recover exactly the form in which they stood either in his own original manuscripts or in those manuscripts, or transcripts of them, after they had been prepared for use in the theatre. Still less can we hope to pinpoint the words spoken in any particular performance. Nevertheless, it is in performance that the plays lived and had their being. Performance is the end to which they were created, and in this edition we have devoted our efforts to recovering and presenting texts of Shakespeare’s plays as they were acted in the London playhouses which stood at the centre of his professional life.

A USER’S GUIDE TO THE COMPLETE WORKS

Readers of this edition may find it helpful to have a note of some of its more distinctive features. Fuller discussion is to be found in the General Introduction, and in the

Textual Companion (

1987

)

.

ContentsTextual Companion (

1987

)

.

This volume includes all the writings believed by the editors to have been written, wholly or in part, by Shakespeare. Like all other editions, it also prints a few poems of uncertain authorship (see Various Poems, pp. 805-811). Information about reasons for inclusion and exclusion can be found in the

Textual Companion

, ‘The Canon and Chronology of Shakespeare’s Plays’, pp. 69-144).

IntroductionsTextual Companion

, ‘The Canon and Chronology of Shakespeare’s Plays’, pp. 69-144).

Each work is preceded by a brief introduction summarizing essential background information.

OrderThe works are printed in conjectured order of composition as determined by the editors. The simplest way to find any given work is to refer to the Alphabetical List of Contents (pp. xi-xii). (Short poems are listed under the general title of ‘Various Poems’.)

The WordsEvery new edition of Shakespeare differs to some extent from its predecessors. Because this edition represents a radical rethinking of the text, it departs from tradition more than most. New emendations of disputed readings have been introduced. At times we restore original readings that have traditionally been emended. Spelling and punctuation have been thoroughly reconsidered (see General Introduction, pp. xv-xlii). Our most radical departures from tradition relate to the plays that survive in more than one early text. In the belief that these texts are more likely to reflect unrevised and revised versions, rather than differently corrupted versions of a lost original (as has generally been supposed), we have abandoned the tradition of conflation. Passages surviving only in a text that we have not selected as our base text are printed not in the body of the play but as Additional Passages (as, for example, at the end of

Hamlet

). Most drastically, we present separately edited texts of both authoritative early editions of

King Lear

, using the titles under which they first appeared (

The History of King Lear

for the quarto text of 1608, and

The Tragedy of King Lear

for the Folio text). The only text in the volume printed from manuscript,

Sir Thomas More

, calls for individual treatment, which is discussed in the introduction to the play.

Hamlet

). Most drastically, we present separately edited texts of both authoritative early editions of

King Lear

, using the titles under which they first appeared (

The History of King Lear

for the quarto text of 1608, and

The Tragedy of King Lear

for the Folio text). The only text in the volume printed from manuscript,

Sir Thomas More

, calls for individual treatment, which is discussed in the introduction to the play.

Other books

One by One by Chris Carter

Lady In Waiting by Kathryn Caskie

The Twitter History of the World by Kelvin MacKenzie

Reign of Hell by Sven Hassel

Rock Chick 04 Renegade by Kristen Ashley

Burned: Devil's Blaze MC Book 2 by Jordan Marie

The Shining Company by Rosemary Sutcliff

Catnapped (A Klepto Cat Mystery) by Fry, Patricia

American Indian Trickster Tales (Myths and Legends) by Richard Erdoes, Alfonso Ortiz

Motherlode by James Axler