William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition (7 page)

Read William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition Online

Authors: William Shakespeare

Tags: #Drama, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare

BOOK: William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition

4.82Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

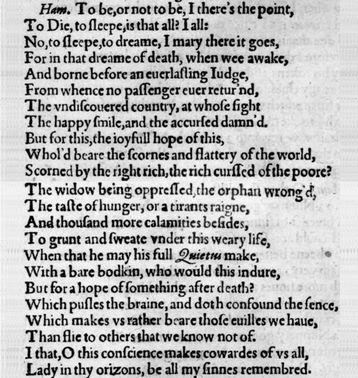

11. ‘To be or not to be’ as it appeared in the ‘bad’ quarto of 1603

Although in general, companies which owned play scripts preferred not to allow them to be printed, some of Shakespeare’s plays were printed from authentic manuscripts during his lifetime, and even while they were still being performed by his company; these have often been designated as ‘good’ quartos. First came

Titus Andronicus,

printed in 1594 from Shakespeare’s own papers, probably because the company for which he wrote it had been disbanded. In 1597

Richard II

was printed perhaps directly from Shakespeare’s manuscript, minus the politically sensitive episode (in 4.1) in which Richard gives up his crown to Bolingbroke: a clear instance of censorship, whether self-imposed or not. The first play to be published from the outset in Shakespeare’s name is Love’s Labour’s Lost, in 1598. Several other quartos printed from good manuscripts appeared around the same time: I

Henry IV

(probably from a scribal transcript) in 1598, and A

Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, 2 Henry IV

, and

Much Ado About Nothing

(all evidently from Shakespeare’s papers) in 1600. In 1604 appeared a new text of

Hamlet

printed from Shakespeare’s own papers and declaring itself to be ‘Newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much again as it was, according to the true and perfect copy’: surely an attempt to replace a bad text by a good one.

King Lear

followed, in 1608, in a badly printed quarto whose status has been much disputed, but which we believe to derive from Shakespeare’s own manuscript. In 1609 came

Troilus and Cressida,

probably from Shakespeare’s own papers, in an edition which in the first-printed copies claims to present the play ‘as it was acted by the King’s majesty’s servants at the Globe‘, but in copies printed later in the print-run declares that it has never been ‘staled with the stage’. The only new play to appear between Shakespeare’s death and the publication of the Folio in 1623 was

Othello

, printed in 1622 apparently from a transcript of Shakespeare’s own papers.

Titus Andronicus,

printed in 1594 from Shakespeare’s own papers, probably because the company for which he wrote it had been disbanded. In 1597

Richard II

was printed perhaps directly from Shakespeare’s manuscript, minus the politically sensitive episode (in 4.1) in which Richard gives up his crown to Bolingbroke: a clear instance of censorship, whether self-imposed or not. The first play to be published from the outset in Shakespeare’s name is Love’s Labour’s Lost, in 1598. Several other quartos printed from good manuscripts appeared around the same time: I

Henry IV

(probably from a scribal transcript) in 1598, and A

Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, 2 Henry IV

, and

Much Ado About Nothing

(all evidently from Shakespeare’s papers) in 1600. In 1604 appeared a new text of

Hamlet

printed from Shakespeare’s own papers and declaring itself to be ‘Newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much again as it was, according to the true and perfect copy’: surely an attempt to replace a bad text by a good one.

King Lear

followed, in 1608, in a badly printed quarto whose status has been much disputed, but which we believe to derive from Shakespeare’s own manuscript. In 1609 came

Troilus and Cressida,

probably from Shakespeare’s own papers, in an edition which in the first-printed copies claims to present the play ‘as it was acted by the King’s majesty’s servants at the Globe‘, but in copies printed later in the print-run declares that it has never been ‘staled with the stage’. The only new play to appear between Shakespeare’s death and the publication of the Folio in 1623 was

Othello

, printed in 1622 apparently from a transcript of Shakespeare’s own papers.

Not much money was to be made from printing a single edition of a play, but some of these quartos were several times reprinted. In the right circumstances Shakespeare could be a valuable property to a publisher. He and his company, however, would have benefited only from the one-off return of selling a manuscript for publication. It is not clear why they released reliable texts of some plays but not others. As a shareholder in the company to which the plays belonged, Shakespeare himself must have been a partner in its decisions, and it is difficult to believe that he was so lacking in personal vanity that he was happy to be represented in print by garbled texts; but he seems to have taken no interest in the progress of his plays through the press, and only two plays,

Romeo and Juliet

and

Hamlet,

were printed in debased quartos that were replaced with fuller quarto texts. Even some of those printed from authentic manuscripts—such as the 1604

Hamlet

—are badly printed, and certainly not proof-read by the author; none of them bears an author’s dedication or shows any sign of having been prepared for the press in the way that, for instance, Ben Jonson clearly prepared some of his plays. John Marston, introducing the printed text of his play

The Malcontent

in 1604, wrote: ‘Only one thing afflicts me, to think that scenes invented merely to be spoken, should be enforcively published to be read.’ Perhaps Shakespeare was similarly afflicted.

Romeo and Juliet

and

Hamlet,

were printed in debased quartos that were replaced with fuller quarto texts. Even some of those printed from authentic manuscripts—such as the 1604

Hamlet

—are badly printed, and certainly not proof-read by the author; none of them bears an author’s dedication or shows any sign of having been prepared for the press in the way that, for instance, Ben Jonson clearly prepared some of his plays. John Marston, introducing the printed text of his play

The Malcontent

in 1604, wrote: ‘Only one thing afflicts me, to think that scenes invented merely to be spoken, should be enforcively published to be read.’ Perhaps Shakespeare was similarly afflicted.

In 1616, the year of Shakespeare’s death, Ben Jonson published his own collected plays in a handsome Folio. It was the first time that an English writer for the popular stage had been so honoured (or had so honoured himself), and it established a precedent by which Shakespeare’s fellows could commemorate their colleague and friend. Principal responsibility for this ambitious enterprise was undertaken by John Heminges and Henry Condell, both long-established actors with Shakespeare’s company; latterly, Heminges had been its business manager. They, along with Richard Burbage, had been the colleagues whom Shakespeare remembered in his will: he left each of them 26s. 8d. to buy a mourning ring. Although the Folio did not appear until 1623, they may have started planning it soon after—or even before—Shakespeare died: big books take a long time to prepare. And they undertook their task with serious care. Most importantly, they printed eighteen plays that had not so far appeared in print, and which might otherwise have vanished. Their decision not to include

Edward III

suggests at least that they did not believe Shakespeare to have written all of it. They omitted (so far as we can tell) only

Pericles, Cardenio

(now vanished),

The Two Noble Kinsmen

—perhaps because these three were collaborative—and the mysterious

Love’s Labour’s Won

(

see

p. 337). And they went to considerable pains to provide good texts. They had no previous experience as editors; they may have had help from others (including Ben Jonson, who wrote commendatory verses for the Folio): anyhow, although printers find it easier to set from print than from manuscript, they were not content simply to reprint quartos whenever they were available. In fact they seem to have made a conscious effort to identify and to avoid making use of the quartos now recognized as unauthoritative. In their introductory epistle addressed ‘To the Great Variety of Readers’ they declare that the public has been ‘abused with divers stolen and surreptitious copies, maimed and deformed by the frauds and stealths of injurious impostors’. But now these plays are ‘offered to your view cured and perfect of their limbs, and all the rest absolute in their numbers, as he conceived them’.

Edward III

suggests at least that they did not believe Shakespeare to have written all of it. They omitted (so far as we can tell) only

Pericles, Cardenio

(now vanished),

The Two Noble Kinsmen

—perhaps because these three were collaborative—and the mysterious

Love’s Labour’s Won

(

see

p. 337). And they went to considerable pains to provide good texts. They had no previous experience as editors; they may have had help from others (including Ben Jonson, who wrote commendatory verses for the Folio): anyhow, although printers find it easier to set from print than from manuscript, they were not content simply to reprint quartos whenever they were available. In fact they seem to have made a conscious effort to identify and to avoid making use of the quartos now recognized as unauthoritative. In their introductory epistle addressed ‘To the Great Variety of Readers’ they declare that the public has been ‘abused with divers stolen and surreptitious copies, maimed and deformed by the frauds and stealths of injurious impostors’. But now these plays are ‘offered to your view cured and perfect of their limbs, and all the rest absolute in their numbers, as he conceived them’.

None of the quartos believed by modern scholars to be unauthoritative was used unaltered as copy for the Folio. As men of the theatre, Heminges and Condell had access to theatre copies, and they made considerable use of them. For some plays, such as Titus

Andronicus

(which includes a whole scene not present in the quarto), and

A Midsummer Night’s Dream,

the printers had a copy of a quarto (not necessarily the first) marked up with alterations made as the result of comparison with a theatre manuscript. For other plays (the first four to be printed in the Folio—

The Tempest, The Two Gentlemen of Verona

,

The Merry Wives of Windsor

, and

Measure for Measure

—along with

The Winter’s Tale and

probably

Othello

) they employed a professional scribe, Ralph Crane, to transcribe papers in the theatre’s possession. For others, such as Henry V and

All’s Well That Ends Well

, they seem to have had authorial papers; and for yet others, such as

Macbeth

, a theatre manuscript. We cannot always be sure of the copy used by the printers, and sometimes it may have been mixed: for

Richard III

they seem to have used pages of the third quarto mixed with pages of the sixth quarto combined with passages in manuscript; a copy of the third quarto of

Richard II

, a copy of the fifth quarto, and a theatre manuscript all contributed to the Folio text of that play; the annotated third quarto of

Titus Andronicus

was supplemented by the ‘fly’ scene (3.2) which Shakespeare appears to have added after the play was first composed. Dedicating the Folio to the brother Earls of Pembroke and Montgomery, Heminges and Condell claimed that, in collecting Shakespeare’s plays together, they had ‘done an office to the dead to procure his orphans guardians’ (that is, to provide noble patrons for the works he had left behind), ‘without ambition either of self profit or fame, only to keep the memory of so worthy a friend and fellow alive as was our Shakespeare’. Certainly they deserve our gratitude.

The Modern Editor’s TaskAndronicus

(which includes a whole scene not present in the quarto), and

A Midsummer Night’s Dream,

the printers had a copy of a quarto (not necessarily the first) marked up with alterations made as the result of comparison with a theatre manuscript. For other plays (the first four to be printed in the Folio—

The Tempest, The Two Gentlemen of Verona

,

The Merry Wives of Windsor

, and

Measure for Measure

—along with

The Winter’s Tale and

probably

Othello

) they employed a professional scribe, Ralph Crane, to transcribe papers in the theatre’s possession. For others, such as Henry V and

All’s Well That Ends Well

, they seem to have had authorial papers; and for yet others, such as

Macbeth

, a theatre manuscript. We cannot always be sure of the copy used by the printers, and sometimes it may have been mixed: for

Richard III

they seem to have used pages of the third quarto mixed with pages of the sixth quarto combined with passages in manuscript; a copy of the third quarto of

Richard II

, a copy of the fifth quarto, and a theatre manuscript all contributed to the Folio text of that play; the annotated third quarto of

Titus Andronicus

was supplemented by the ‘fly’ scene (3.2) which Shakespeare appears to have added after the play was first composed. Dedicating the Folio to the brother Earls of Pembroke and Montgomery, Heminges and Condell claimed that, in collecting Shakespeare’s plays together, they had ‘done an office to the dead to procure his orphans guardians’ (that is, to provide noble patrons for the works he had left behind), ‘without ambition either of self profit or fame, only to keep the memory of so worthy a friend and fellow alive as was our Shakespeare’. Certainly they deserve our gratitude.

It will be clear from all this that the documents from which even the authoritative early editions of Shakespeare’s plays were printed were of a very variable nature. Some were his own papers in a rough state, including loose ends, duplications, inconsistencies, and vaguenesses. At the other extreme were theatre copies representing the play as close to the state in which it appeared in Shakespeare’s theatre as we can get; and there were various intermediate states. For those plays of which we have only one text—those first printed in the Folio, along with

Pericles, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and Edward III

-the editor is at least not faced with the problem of alternative choices. The surviving text of

Macbeth

gives every sign of being an adaptation: if so, there is no means of recovering what Shakespeare originally wrote. The scribe seems to have entirely expunged Shakespeare’s stage directions from

The Two Gentlemen of Verona

: we must make do with what we have. Other plays, however, confront the editor with a problem of choice. Pared down to its essentials, it is this: should readers be offered a text which is as close as possible to what Shakespeare originally wrote, or should the editor aim to formulate a text presenting the play as it appeared when performed by the company of which Shakespeare was a principal shareholder in the theatres that he helped to control and on whose success his livelihood depended? The problem exists in two different forms. For some plays, the changes made in the more theatrical text (always the Folio, if we discount the bad quartos) are relatively minor, consisting perhaps in a few reallocations of dialogue, the addition of music cues to the stage directions, and perhaps some cuts. So it is with, for example, A Midsummer

Night’s Dream and Richard II.

More acute—and more critically exciting—are the problems raised when the more theatrical version appears to represent, not merely the text as originally written after it had been prepared for theatrical use, but a more radical revision of that text made (in some cases) after the first version had been presented in its own terms. At least five of Shakespeare’s plays exist in these states: they are 2

Henry IV, Hamlet, Troilus and Cressida, Othello,

and

King Lear.

Pericles, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and Edward III

-the editor is at least not faced with the problem of alternative choices. The surviving text of

Macbeth

gives every sign of being an adaptation: if so, there is no means of recovering what Shakespeare originally wrote. The scribe seems to have entirely expunged Shakespeare’s stage directions from

The Two Gentlemen of Verona

: we must make do with what we have. Other plays, however, confront the editor with a problem of choice. Pared down to its essentials, it is this: should readers be offered a text which is as close as possible to what Shakespeare originally wrote, or should the editor aim to formulate a text presenting the play as it appeared when performed by the company of which Shakespeare was a principal shareholder in the theatres that he helped to control and on whose success his livelihood depended? The problem exists in two different forms. For some plays, the changes made in the more theatrical text (always the Folio, if we discount the bad quartos) are relatively minor, consisting perhaps in a few reallocations of dialogue, the addition of music cues to the stage directions, and perhaps some cuts. So it is with, for example, A Midsummer

Night’s Dream and Richard II.

More acute—and more critically exciting—are the problems raised when the more theatrical version appears to represent, not merely the text as originally written after it had been prepared for theatrical use, but a more radical revision of that text made (in some cases) after the first version had been presented in its own terms. At least five of Shakespeare’s plays exist in these states: they are 2

Henry IV, Hamlet, Troilus and Cressida, Othello,

and

King Lear.

The editorial problem is compounded by the existence of conflicting theories to explain the divergences between the surviving texts of these plays. Until recently, it was generally believed that the differences resulted from imperfect transmission: that Shakespeare wrote only one version of each play, and that each variant text represents that original text in a more or less corrupt form. As a consequence of this belief, editors conflated the texts, adding to one passages present only in the other, and selecting among variants in wording in an effort to present what the editor regarded as the most ‘Shakespearian’ version possible.

Hamlet

provides an example. The 1604 quarto was set from Shakespeare’s own papers (with some contamination from the reported text of 1603). The Folio includes about 80 lines that are not in the quarto, but omits about 23 that are there. The Folio was clearly influenced by, if not printed directly from, a theatre manuscript. There are hundreds of local variants. Editors have conflated the two texts, assuming that the absence of passages from each was the result either of accidental omission or of cuts made in the theatre against Shakespeare’s wishes; they have also rejected a selection of the variant readings. It is at least arguable that this produces a version that never existed in Shakespeare’s time. We believe that the 1604 quarto represents the play as Shakespeare first wrote it, before it was performed, and that the Folio represents a theatrical text of the play after he had revised it. Given this belief, it would be equally logical to base an edition on either text: one the more literary, the other the more theatrical. Both types of edition would be of interest; each would present within its proper context readings which editors who conflate the texts have to abandon.

Hamlet

provides an example. The 1604 quarto was set from Shakespeare’s own papers (with some contamination from the reported text of 1603). The Folio includes about 80 lines that are not in the quarto, but omits about 23 that are there. The Folio was clearly influenced by, if not printed directly from, a theatre manuscript. There are hundreds of local variants. Editors have conflated the two texts, assuming that the absence of passages from each was the result either of accidental omission or of cuts made in the theatre against Shakespeare’s wishes; they have also rejected a selection of the variant readings. It is at least arguable that this produces a version that never existed in Shakespeare’s time. We believe that the 1604 quarto represents the play as Shakespeare first wrote it, before it was performed, and that the Folio represents a theatrical text of the play after he had revised it. Given this belief, it would be equally logical to base an edition on either text: one the more literary, the other the more theatrical. Both types of edition would be of interest; each would present within its proper context readings which editors who conflate the texts have to abandon.

It would be extravagant in a one-volume edition to present double texts of all the plays that exist in significantly variant form. The theatrical version is, inevitably, that which comes closest to the ‘final’ version of the play. We have ample testimony from the theatre at all periods, including our own, that play scripts undergo a process of, often, considerable modification on their way from the writing table to the stage. Occasionally, dramatists resent this process; we know that some of Shakespeare’s contemporaries resented cuts made in some of their plays. But we know too that plays may be much improved by intelligent cutting, and that dramatists of great literary talent may benefit from the discipline of the theatre. It is, of course, possible that Shakespeare’s colleagues occasionally overruled him, forcing him to omit cherished lines, or that practical circumstances—such as the incapacity of a particular actor to do justice to every aspect of his role—necessitated adjustments that Shakespeare would have preferred not to make. But he was himself, supremely, a man of the theatre. We have seen that he displayed no interest in how his plays were printed: in this he is at the opposite extreme from Ben Jonson, who was still in mid-career when he prepared the collected edition of his works. We know that Shakespeare was an actor and shareholder in the leading theatre company of its time, a major financial asset to that company, a man immersed in the life of that theatre and committed to its values. The concept of the director of a play did not exist in his time; but someone must have exercised some, at least, of the functions of the modern director, and there is good reason to believe that that person must have been Shakespeare himself, for his own plays. The very fact that those texts of his plays that contain cuts also give evidence of more ‘literary’ revision suggests that he was deeply involved in the process by which his plays came to be modified in performance. For these reasons, this edition chooses, when possible, to print the more theatrical version of each play. In some cases, this requires the omission from the body of the text of lines that Shakespeare certainly wrote; there is, of course, no suggestion that these lines are unworthy of their author; merely that, in some if not all performances, he and his company found that the play’s overall structure and pace were better without them. All such lines are printed as Additional Passages at the end of the play.

Other books

Pirates! by Celia Rees

Moment of Weakness (Embracing Moments Book 1) by Katie Fox

On Wings of Chaos (Revenant Wyrd Book 5) by Travis Simmons

Knowing by Laurel Dewey

Whisper to the Blood by Dana Stabenow

Timothy Boggs - Hercules Legendary Joureneys 02 by Serpent's Shadow

Afterlife by Douglas Clegg

The Death Seer (Skeleton Key) by Tanis Kaige, Skeleton Key

Eliza Lloyd by One Last Night

Snow Kills by Rc Bridgestock