Why the West Rules--For Now (65 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

But like all the spacemen I have imagined so far, they would have been mistaken, because another historical law was also operating. I commented earlier that not even Genghis Khan could step into the same river twice; and neither could the horsemen of the apocalypse. The cores across which the horsemen rode during the Second Old World Exchange were very different from those they had devastated during the First Old World Exchange, which meant that the Second Exchange had very different consequences from the First.

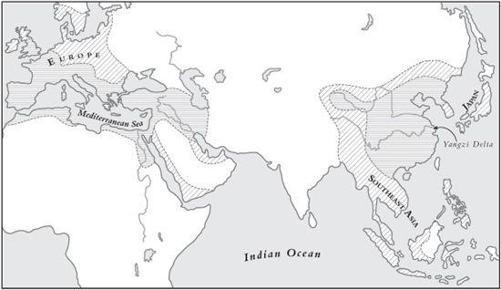

Most obviously, both cores were geographically bigger when the Second Exchange intensified around 1200 than they had been during the First (

Figure 8.5

), and size mattered. On the one hand, larger cores generated larger disruptions: it is hard to quantify calamity, but the plagues, famines, and migrations that began in the thirteenth century do seem to have been even worse than those that began in the second century. On the other hand, though, larger cores also meant greater depth to absorb shocks and larger reserves to hasten recovery. Japan, Southeast Asia, the Mediterranean Basin, and most of Europe escaped Mongol devastation in the thirteenth century; Japan and Southeast Asia avoided the Black Death in the fourteenth too; and in the very heart of China the Yangzi Delta region seems to have come through the disasters remarkably well.

Economic geography had also changed. Around 100

CE

the Western core was richer and more developed than the Eastern, but by 1200 the reverse was true. It was the Eastern core, not the Western, that was now straining against the hard ceiling, and Eastern commercial networks (especially those linking southern China, Southeast Asia, and the Indian Ocean) dwarfed anything in the West.

Figure 8.5. Size matters: horizontal lines mark areas in the Eastern and Western cores ruled by states around 100

CE

, on the eve of the first Old World crisis, and diagonal lines show where states had spread by 1200, just before the second crisis

Changes in political geography reinforced economics. Back in 100

CE

most trade in each core had gone on within the boundaries of a single great empire; by 1200 that was no longer true. Both cores were politically messier than they had been in antiquity, and even when great empires once again consolidated the old heartlands after the Black Death, the political relationships were very different. Any great empire now had to deal with a surrounding ring of smaller states. In the East the relationships were mainly commercial and diplomatic; in the West they were mainly violent.

Put together, these changes meant that the cores not only recovered faster from the Second Old World Exchange than from the First but also recovered in different ways.

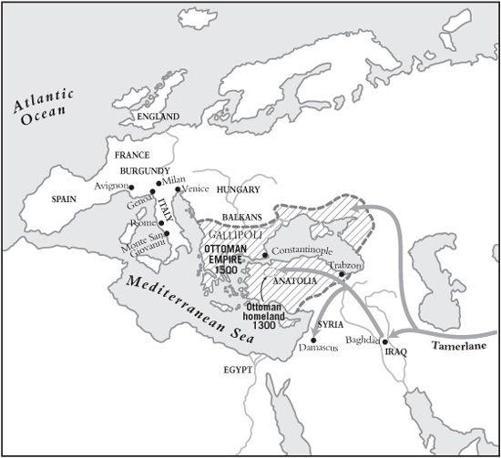

In the West the Ottoman Turks quickly rebuilt an empire in the old heartland in the fourteenth century. The Ottomans were just one of dozens of Turkic clans that settled in Anatolia around 1300 after the Mongols had shattered the older Muslim kingdoms (

Figure 8.6

), but within a few years of the Black Death they had already got the better of their rivals and established a European bridgehead. By the 1380s they were bullying the pitiful remnants of the Byzantine Empire, and by 1396 they scared Christendom so badly that the squabbling popes of Rome and Avignon briefly agreed to join forces in sending a crusade against them.

It was a disaster, but Christian hopes briefly revived when Tamerlane, a Mongol chieftain who made Genghis Khan look well adjusted, led new steppe incursions into the Muslim world. In 1400 the Mongols annihilated Damascus and in 1401 sacked Baghdad, reportedly using the skulls of ninety thousand of its residents as bricks for a series of towers they built around the ruins. In 1402 Tamerlane defeated the Ottomans and threw the sultan into a cage, where he expired of shame and exposure. But then Christian hopes failed. Instead of staying to devastate the remaining Muslim lands, Tamerlane decided that the emperor of distant China had insulted him and swung his horsemen around. He died in 1405 while riding east to avenge the slight.

Saved by the bell, the Ottomans bounced back into business within twenty years, but as they advanced through the Balkans they had to learn some tough lessons. When the Mongols defeated them in 1402 both armies had fought as steppe warriors had done for two thousand years, with clouds of mounted archers enveloping and shooting down

slower-moving foes. European armies could not compete head-to-head with these swarms of light horsemen, but they had improved their newfangled guns to the point that in 1444 a Hungarian army gave the ottomans a nasty shock. With small cannons mounted on wagons that were roped together as mobile forts, Hungarian firepower stopped the Turkish cavalry in its tracks. Had the Hungarian king not galloped out ahead of his men and got himself killed he probably would have won the day.

Figure 8.6. The revival of the West, 1350–1500. The shaded area shows the extent of the ottoman Turkish empire in 1500—by which time the Western core was moving decisively northward and westward.

The Turks, quick learners, figured out the best response: buy European firepower. This new technology was expensive, but even Europe’s richest states, such as Venice and Genoa, were paupers next to the sultans. Hiring Italians as admirals and siege engineers, training

enslaved Christian boys as an elite infantry corps, and recruiting European gunners, the Ottomans were soon on the move again. When they began their 1453 assault on Constantinople, still the greatest fortress on earth and the main barrier to Turkish power, the Turks hired away the Byzantines’ top gunner, a Hungarian. This gunner made the Ottomans an iron cannon big enough to throw a thousand-pound stone ball, with a roar loud enough (chroniclers said) to make pregnant women miscarry. The gun in fact cracked on the second day and was useless by the fourth or fifth, but the Hungarian also cast smaller, more practical cannon that succeeded where the giant failed.

For the first and only time in its history, Constantinople’s walls failed. Thousands of panic-stricken Byzantines crowded into the church of Hagia Sophia—“

the earthly heaven

, the second firmament, the vehicle of the cherubim, the throne of the glory of God,” Gibbon called it—trusting in a prophecy that when infidels attacked the church an angel would descend, sword in hand, to restore the Roman Empire. But no angel came; Constantinople fell; and with it, Gibbon concluded, the Roman Empire finally expired.

*

As the Turks advanced, European kings fought more fiercely against one another as well as against the infidel, and a genuine arms race took off. France and Burgundy led the way in the 1470s, their gunners casting cannons with thicker barrels, forming gunpowder into corns that ignited faster, and using iron rather than stone cannonballs. The result was smaller, stronger, and more portable guns that rendered older weapons obsolete. The new guns were light enough to be loaded onto expensive new warships, driven by sails, not oars, with gun ports cut so low in the hull that iron cannonballs could hole enemy ships right at the waterline.

It was hard for anyone but a king to afford this kind of technology, and slowly but surely western European monarchs bought enough of the new weapons to intimidate the lords, independent cities, and bishops whose messy, overlapping jurisdictions had made earlier European

states so weak. Along the Atlantic littoral, kings created bigger, stronger states—France, Spain, and England—within which the royal writ ran everywhere and the nation, not far-flung aristocratic clans or popes in Rome, had first claim on people’s loyalties. And once they had muscled their lords aside, kings could build up bureaucracies, tax the people directly, and buy more guns—which of course forced neighboring kings to buy more guns too, and pushed everyone to raise still more money.

Once again there were advantages to backwardness, and the struggle steadily pulled the West’s center of gravity toward the Atlantic. The cities of northern Italy had long been the most developed part of Europe, but now discovered a disadvantage of forwardness: glorious city-states such as Milan and Venice were too rich and powerful to be bullied into any Italian national state, but not rich or powerful enough to stand alone against genuine national states such as France and Spain. Writers such as Machiavelli rejoiced in this liberty, but its price became crystal clear when a French army invaded Italy in 1494. Italian war-making had declined, as Machiavelli himself conceded, “

into such a state

of decay that wars were commenced without fear, continued without danger, and concluded without loss.” A few dozen up-to-date French cannons now blew away everything in their path. It took them just eight hours to smash the great stone castle of Monte San Giovanni, killing seven hundred Italians for the loss of ten Frenchmen. Italian cities could not begin to compete with the tax revenues of big states such as France. By 1500 the Western core was being reordered from its Atlantic fringe, and war was leading the way.

The Eastern core, by contrast, was reordered from its ancient center in China, and commerce and diplomacy ultimately led the way, even though the rise of new empires began in bloodshed as grim as anything in the West. Zhu Yuanzhang, the founder of the Ming dynasty that reunited China, had been born into poverty in 1328 as Mongol power was falling apart. His parents—migrant laborers on the run from tax collectors—sold four of his brothers and sisters because they could not feed them, and abandoned Yuanzhang, their youngest, with a Buddhist grandfather. The old man filled the boy’s head with the messianic visions of the Red Turbans, one of many resistance movements fighting Mongol rule. The end was nigh, the old man insisted, and the Buddha

would soon return from Paradise to smite the wicked. Instead, in the locust-and drought-ravaged summer of 1344, disease—quite likely the Black Death—carried off Yuanzhang’s whole family.

The teenager attached himself to a Buddhist monastery as a servant, but the monks could barely feed themselves and sent him out to beg or steal for his keep. After wandering southern China’s back roads for three or four years he returned to the monastery just in time to see it burned to the ground in the vast, roiling civil wars that accompanied the collapse of Mongol rule. With nowhere else to go, he joined the other monks in hanging around the smoking ruins, starving.

Yuanzhang was an alarming-looking youth, tall, ugly, lantern-jawed, and pockmarked. But he was also smart, tough, and (thanks to the monks) literate; the kind of man, in short, that any bandit would want in his gang. Recruited by a band of Red Turbans as they passed through the neighborhood, he impressed the other thugs and visionaries, married the chief’s daughter, and eventually took over the gang.

In a dozen years of grinding warfare Yuanzhang turned his cutthroat crew into a disciplined army and drove the other rebels from the Yangzi Valley. Just as important, he distanced himself from the Red Turbans’ wilder prophecies and organized a bureaucracy that could run an empire. In January 1368, just shy of his fortieth birthday, he renamed himself Hongwu (“Vast Military Power”) and proclaimed the creation of a Ming (“Brilliant”) dynasty.

Hongwu’s official pronouncements make it sound as if his whole adult life was a reaction against his terrible, rootless, violent youth. He promoted an image of China as a bucolic paradise of stable, peaceful villages, where virtuous elders supervised self-sufficient farmers, traders dealt only in goods that could not be made locally, and—unlike Hongwu’s own family—no one moved around. Hongwu claimed that few people needed to travel more than eight miles from home, and that covering more than thirty-five miles without permission should earn a whipping. Fearing that commerce and coinage would corrode stable relationships, three times he passed laws restricting trade with foreigners to government-approved dealers and even prohibited foreign perfumes lest they seduce the Chinese into illicit exchanges. By 1452 his successors had renewed his laws three more times and had four times banned silver coins out of fear they would make unnecessary commerce too easy.