Why the West Rules--For Now (52 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

A peculiar standoff developed. The Goths were not nomads like the Xiongnu, stealing things and then riding off to the steppes, nor were they imperialists like the Persians, come to annex provinces. They wanted to carve out their own enclave in the empire. But with no siege engines to storm cities and no administration to run them, they needed Roman cooperation; and when that was not forthcoming they rattled around the Balkans, trying to blackmail Constantinople into granting them their own kingdom. Lacking legions to expel them, the eastern emperor pleaded poverty, bribed the Goths, and skirmished with them, until, in 401, he persuaded them that they would get a better deal by migrating westward, whereupon they became his co-emperor’s problem.

But all this clever diplomacy ceased to matter in 405 when the Huns resumed their western progress. More dominos fell and more Germanic tribes pressed against Rome’s frontiers. The legions, now chiefly made up of Germanic immigrants and led by a half-German general, wore them down in bloody campaigns, and diplomats wove yet more webs, but on New Year’s Eve, 406, Rome finally lost control when thousands of Germans poured across the frozen Rhine. There were no more armies to stop them. The immigrants fanned out, taking everything. The poet Sidonius, among the richest of the rich, described the indignities he had to endure when a band moved onto his estate in Gaul. “

Why ask for a song

to Venus,” he wrote to a correspondent living back in Rome, “when I’m stuck in the middle of a long-haired rabble, forced to listen to Germanic speech, keeping a straight face while I praise songs from a swinish Burgundian who spreads rancid butter in his hair? … You don’t have the stink of garlic and onions from ten breakfasts belched on you early every morning.” Plenty would have envied Sidonius, though. Another eyewitness put things more bluntly: “

All Gaul

is filled with the smoke of a single funeral pyre.”

The army in Britain rebelled, taking charge of its own defense, and in 407 what remained of the Rhine armies joined it. By then everything was falling apart. Struggling to get the western Roman emperor’s attention amid so many disasters, the Goths invaded Italy in 408 and in 410 sacked Rome itself. They finally got their deal in 416, with the emperor agreeing that if the Goths helped him drive the Germans

and assorted usurpers out of Gaul and Spain, they could keep part of the territory.

Rome’s frontiers, like China’s, had become places where barbarians (as each empire called outsiders) settled and then took imperial pay to defend the empire against more barbarians trying to push their way in. It was a lose-lose situation for the emperors. When the Germanic Goths (now fighting on Rome’s side) defeated the Germanic Vandals (fighting against Rome) in Spain in 429, the Vandals crossed to North Africa. It may seem hard to believe, but what is today the Tunisian Sahara Desert was then Rome’s breadbasket, ten thousand square miles of irrigated fields, exporting half a million tons of grain to Italy each year. Without this food, the city of Rome would starve; without the taxes on it, Rome could not pay its own Germans to fight enemy Germans.

For another ten years brilliant Roman generals and diplomats (themselves often of German stock) managed to keep the Vandals in check and parts of Gaul and Spain loyal, but in 439 it all came crashing down. The Vandals overran Carthage’s agricultural hinterland and Rome’s worst-case scenario abruptly materialized.

Rulers in Constantinople were often quite happy to see their potential rivals in Rome struggling, but the prospect of the western parts of the empire actually breaking up alarmed the eastern emperor Theodosius II enough that he mustered a large force to help liberate what is now Tunisia. But as his troops gathered in 441, yet another blow fell. A new king of the Huns, Attila—the “Scourge of God,” as Roman authors called him—erupted into the Balkans, leading not just ferocious cavalry but also a modern siege train. (Refugees from Constantinople may have brought him this technology; an ambassador from Theodosius described meeting such an exile at Attila’s court in 449.)

As his cities crumbled under the Huns’ battering rams, Theodosius canceled the attack on the Vandals. He saved Constantinople—just—but these were dark days for Rome. The city still had perhaps 800,000 residents around 400

CE

; by 450 three-quarters had left. Tax revenues dried up and the army evaporated, and the worse things got, the more usurpers tried to seize the throne. Attila chose this moment to decide he had squeezed the Balkans dry, and turned west. The half-Gothic commander of Rome’s western armies managed to convince the Goths that Attila was their enemy too, and, leading an almost entirely Germanic force, he dealt Attila the only defeat of his career. Attila died

before he could get revenge. Bursting a blood vessel during a drinking bout to celebrate his umpteenth wedding, the Scourge of God went to meet his maker.

Without Attila the loose Hun Empire disintegrated, leaving the emperors in Constantinople free to try to put the western empire back together again, but not until 467 did all the requirements—money, ships, and a Roman strongman worth backing—fall into place. Emptying his treasury, the eastern emperor sent his admiral Basiliskos with a thousand ships to recapture North Africa and heal the western provinces’ fiscal backbone.

In the end, the fate of the empire came down to the wind. In summer 468, as Basiliskos closed on Carthage, the breezes should have been blowing westward along North Africa’s shore, pushing Basiliskos’ ships along. But at the last moment the wind shifted and trapped them against the coast. The Vandals sent burning hulks into the packed Roman vessels, just the tactics that the English would use against the Spanish Armada in 1588. Ancient ships, with their tinder-dry ropes, wooden decks, and cloth sails, could turn into infernos in seconds. Piled on top of one another, panicking to push the fireships away with poles, and with no room to escape, the Romans lost all order. The Vandals came in for the kill, and it was all over.

In

Chapter 5

I talked about the great-man theory of history, which holds that it is unique geniuses, such as Tiglath-Pileser of Assyria, not grand impersonal forces, such as the Old World Exchange, that shape events. The other side of the great-man coin is the bungling-idiot theory of history: What, we have to ask, would have happened had Basiliskos had the wits not to get trapped against the coast?

*

He probably would have retaken Carthage, but would that have restored the Italy–North Africa fiscal axis? Maybe; the Vandals had been in Africa for less than forty years, and the Roman Empire might have been able to rebuild economic structures quickly. Or then again, maybe not. Odoacer, king of the Goths, the strongest strongman in western Europe, already had his eye on Italy. In 476 he wrote to Zeno, the emperor in Constantinople, observing that the world no longer needed two

emperors. Zeno’s glory was sufficient for everyone, Odoacer said, and he made a proposal: he would run Italy—loyally, of course—on Zeno’s behalf. Zeno understood full well that Odoacer was really announcing his takeover of Italy, but also knew it was no longer worth arguing about.

And so the end of Rome came, not with a bang but a whimper. Would Zeno have been any better placed to defend Italy if Basiliskos had recovered Carthage than he actually was in 476? I doubt it. By this point preserving a Mediterranean-wide empire was beyond anyone’s power, and the fifth century’s frenzied maneuvering, politicking, and killing could do little to change the realities of economic decline, political breakdown, and migrations. The classical world was finished.

SMALLER WORLDS

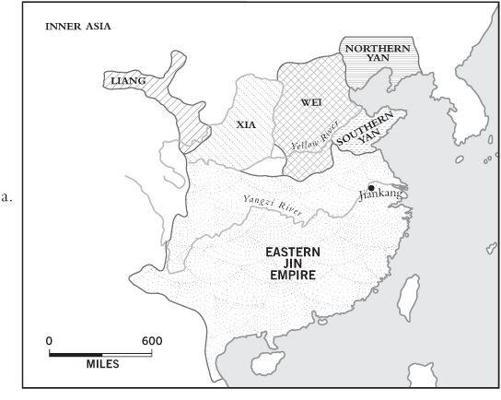

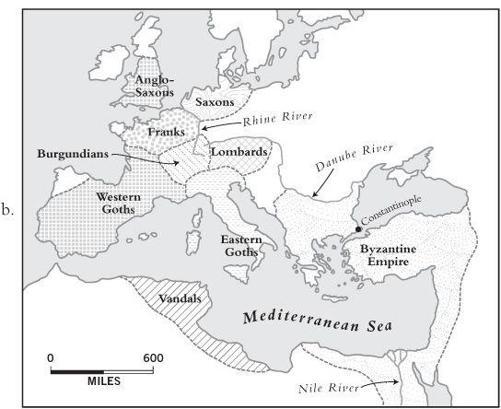

The Eastern and Western cores had each split in two. In China, the Eastern Jin dynasty ruled the southern part of the old empire, but saw themselves as rightful heirs to the whole realm. Similarly, in the West a Byzantine Empire (so called because its capital, Constantinople, stood on the site of the earlier Greek city Byzantium) ruled the eastern part of the old Roman Empire but claimed its entirety (

Figure 6.8

).

The Eastern Jin and Byzantine Empires remained high-end states, with bureaucrats, taxes, and salaried armies. Each boasted great cities and learned scholars, and the farms of the Nile and Yangzi valleys were richer than ever. But neither compared with the Roman and Han empires in their heydays. Their worlds were shrinking as northern China and western Europe slid out of the cores.

Disease, migration, and war had dissolved the networks of managers, merchants, and money that had bound each of the earlier empires into a coherent whole. The new kings of fourth-century northern China and fifth-century western Europe were determinedly low-end, feasting with their long-haired warrior lords in the grand halls they had captured. These kings were happy to take taxes from conquered peasants, but without salaried armies to pay, they did not absolutely need this revenue. They were already rich; they were certainly strong; and trying to manage bureaucracies and extract regular taxes from their unruly followers often seemed more trouble than it was worth.

Figure 6.8. The divided East and West: (a) the Eastern Jin and China’s major immigrant kingdoms, around 400

CE

; (b) Byzantium and Europe’s major immigrant kingdoms, around 500

CE

Many of the old, rich aristocratic families of northern China and the western Roman Empire fled to Jiankang or Constantinople with their treasures, but even more stayed amid the ruins of the old empires, perhaps holding their noses like Sidonius, and made what deals they could with their new masters. They swapped their silk robes for woolen pants, their classical poetry for hunting, and assimilated to the new realities.

Some of those realities turned out to be quite good. The superrich aristocrats of former times, with estates scattered over the whole Han or Roman Empire, disappeared, but even with their properties restricted to a single kingdom, some fourth-and fifth-century landowners remained staggeringly wealthy. The old Roman and Chinese elites intermarried with their conquerors, and moved from the crumbling cities to great manors in the countryside.

As the drift toward low-end states accelerated in the fourth century in northern China and the fifth in western Europe, kings allowed their noblemen to seize as rent the surpluses that peasants had formerly handed over to the taxman. If anything, these surpluses might have been growing as population fell and farmers could concentrate their efforts on the best lands. Countryfolk had lost few of the skills they had learned across the centuries and had indeed added new ones. Drainage techniques in the Yangzi Valley and irrigation in the Nile Valley improved after 300; ox-drawn plows multiplied in northern China; and seed drills, moldboard plows, and watermills spread across western Europe.

But despite all the nobles’ ostentation and the peasants’ ingenuity, the steady thinning of the ranks of bureaucrats, merchants, and managers who had prospered so mightily under the Han and Roman empires meant that the larger economies kept on shrinking at both ends of Eurasia. These characters had often been venal and incompetent, but they really

had

performed a service: by moving goods around they capitalized on different regions’ advantages, and without these go-betweens, economies grew more localized and more oriented toward subsistence.

Trade routes contracted and cities shrank. Southern visitors were shocked by the decay of cities in northern China, and in some parts of the old Roman Empire the decline was so sharp that poets wondered whether the great stone ruins decaying all around them could have

been built by mortals at all. “

Snapped rooftrees

, towers tottering, the work of Giants,” reads an English verse of around 700

CE

. “Rime [mold] scours gatetowers, rime on mortar; shattered are shower shields, roofs ruined. Age underate them.”

In the first century

CE

the emperor Augustus had boasted that he had turned Rome from a city of brick to one of marble, but by the fifth century Europe reverted to a world of wood, with simple shacks thrown up in open spaces between the crumbling shells of old Roman town houses. Nowadays we know quite a lot about these humble homes, but when I started going on digs in England in the 1970s, excavators were still struggling to develop techniques careful enough to recover any traces of them at all.