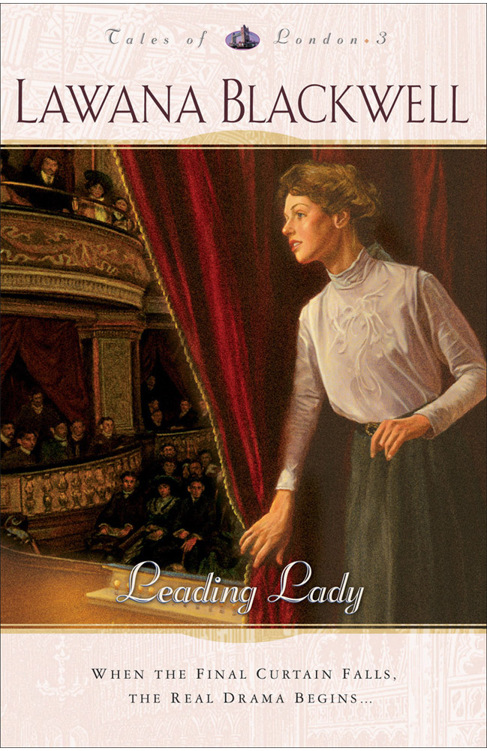

Leading Lady

Authors: Lawana Blackwell

© 2004 by Lawana Blackwell

Published by Bethany House Publishers

11400 Hampshire Avenue South

Bloomington, Minnesota 55438

Bethany House Publishers is a Division of

Baker Book House Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

www.bakerpublishinggroup.com

Ebook edition created 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher and copyright owners. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

ISBN 978-1-4412-7097-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

The internet addresses, email addresses, and phone numbers in this book are accurate at the time of publication. They are provided as a resource. Baker Publishing Group does not endorse them or vouch for their content or permanence.

Scripture quotations are from the King James Version of the Bible.

Cover illustration by Paul Casale

Cover design by Danielle White

This book is dedicated to

my editor and friend,

Ann Parrish

who encourages me every step of the way.

One

“See how she leans her cheek upon her hand!

O that I were a glove upon that hand,

That I might touch that cheek . . .”

The fine-toned male voice coming from the stage was reduced to murmurs when Jewel McGuire closed the wardrobe room door. “Now, that’s what I call good acting,” she said on her way to the drafting table. “We both know what he’d

really

like to do to that cheek.”

Bethia Rayborn raised her eyes from the costume sketches spread out upon the table’s surface, to give her a warning smile. “Funny thing about sounds, cousin. They travel out of a room as well as in.”

Jewel winced. One never knew who could be passing by, and gossip raced through backstage passageways like sharp scissors through silk. Everyone even remotely connected with the Royal Court Theatre was aware of the enmity between its leading actor and actress. But as co-manager with her husband, Jewel was supposed to be more discreet.

Lighted by skylights, the wardrobe room was situated upon the top floor of the honeycomb of rooms to the right of the stage. Rolls of cloth formed a colorful pyramid in one corner; hats queued across shelves; strings of paste pearls and jewels cascaded from the branches of a coat tree; and stockings and belts, gloves and lace collars spilled from cupboard drawers.

The two sewing machines sat idle because seamstresses Mrs. Hamby and Miss Lidstone were at lunch. Noon was far too early for the actors and stage director to be thinking of their stomachs, for their breakfasts would still be digesting. During the run of a play they rarely left the theatre before midnight, which meant daytime schedules lagged accordingly.

As it was impossible to snatch back her words, Jewel wasted

no time fretting over them. She picked up a sketch of a man wearing a Renaissance flatcap, an embroidered doublet over a long pleated undershirt, and silk tights. One-inch squares of fabric were glued along the bottom of the page. “Is this Romeo?”

“Count Paris,” Bethia corrected, and picked up another sketch. “Here’s Romeo. This green velvet will be his cloak for the street-brawl scene, and we’ll line it with this black satin for the Capulet ball.”

“Reversible? How clever.” And only because it was her duty, not because she doubted her younger cousin’s competency, Jewel asked, “Everything will be ready in time?”

She did not have to specify at which date, for the revival of Shakespeare’s

Romeo and Juliet

was scheduled to open on the twenty-eighth of December. Afternoon rehearsals were taking place, now that evening productions of Sydney Grundy’s

Over the Garden Wall

had been running smoothly since the end of August. But Bethia would be returning to Girton College tomorrow.

“In plenty of time,” Bethia assured her. “The patterns are drafted, and the sewing will be completed well before the eleventh, when I’ll be here for final fittings.”

“That’s a comfort. But I must say I’ll be glad when you’re finished with schooling.”

“Not as glad as I’ll be.” Bethia hesitated. “I hope you don’t feel obligated to keep me on because we’re family, Jewel. I would understand perfectly if you’d rather have someone here every day.”

“Nonsense. You’ve less than a year left. I’m not about to lose the best wardrobe mistress in London.”

Her cousin rolled her eyes. “Now you’re just being silly.”

“Only a matter of time,” Jewel said, patting her arm. “And you’re the best

we’ve

ever had.”

It was quite by accident, or then again, by providential design, that Bethia fell into her position. Her talent with a needle became evident when she was only ten and started

asking the housekeeper for scraps from which to fashion clothes for her dolls. She learned sketching from a parlourmaid. And she had inherited her father’s passion for history, the subject she was reading at Girton. The three interests merged when Bethia, home for Lent vacation in her second year, stopped by to watch dress rehearsals for R. Cowrie’s playscript of Sir Walter Scott’s

Ivanhoe.

“I’m afraid Rowena wouldn’t have worn padded undersleeves,” she had whispered after drawing Jewel aside. “They appeared about three hundred years later.”

But when Jewel, only seven months into her position and still quite intimidated by the staff, brought Bethia’s observation to the wardrobe mistress’s attention, Mrs. Wood’s injured reply was, “I was costuming actors when you were still in nappies, Mrs. McGuire. I don’t expect there’ll be anybody in the audience from the twelfth century, so who’s to know the difference?”

The drama critic for the

Times

happened to be one who knew the difference, writing with scathing pen,

The costuming was slipshod, apparently left over from an earlier production of Henry VIII.

When Jewel steeled herself to inform Mrs. Wood that she would have to send all future costume sketches up to Girton so that Bethia could check them for authenticity, the wardrobe mistress resigned in a huff. No suitable replacement had been procured when the time came to plan costuming for Bulwer-Lytton’s

The Lady of Lyons,

and as Bethia happened to be home for summer vacation, she agreed to step in.

The

Times

critic was much appeased, writing,

The settings and costumes were so authentic that at times I almost fancied I could hear the bells of Saint Jean’s Cathedral in the background.

****

“I just wonder how long you can burn the candle at both ends,” Jewel continued.

“I

like

keeping busy.”

Jewel smiled understanding. “It makes the time pass more quickly, yes?”

“I’m sure I don’t know what you mean,” Bethia said, but with a spark in her blue eyes. On both their minds was the absence of Bethia’s longtime beau, Guy Russell, off in Italy studying violin at the University of Bologna.

“Well, at least you’ll both be home for good, come summer.”

“That will be lovely.” Bethia’s wistful smile made her seem younger than her twenty years. She was petite like her mother, with wide blue eyes and freckles scattered across the bridge of her nose. With neither the time nor the inclination to primp, she simply tied her honey-brown hair with a ribbon or a bit of lace at her collar. The plain style suited her oval face. Her even temper and good humor prompted the two seamstresses to work twice as hard as they had under Mrs. Wood with her authoritative ways.

When the seamstresses returned from lunch, Jewel and Bethia chatted with them of patterns and suitable trimmings until three o’clock, when Bethia packed what pages remained of her sketch pad into her satchel. She would be boarding the train tomorrow morning for college and planned to spend the rest of the afternoon with her family.

“I’ll walk you downstairs,” Jewel said, accompanying her out into the corridor. “Grady will want to say good-bye.”

They wrinkled noses at each other at the odors wafting out of the open doorway to the scenic artists’ studio. Paints were the culprits, from the filled jam pots on the long tables to the large framed canvases drying against the walls, waiting to be lowered by winches to the back of the stage. Bethia took the lead on the staircase, with one hand on the railing and the other holding up her sea-green skirt. On the ground floor they went to the office Jewel shared with her husband. Grady McGuire, in shirt-sleeves and waistcoat, and wiping ink from his fingers with a handkerchief, rose from his desk.

“Back to the books, is it now?” he said in his soft Irish brogue.

“She’s never away from the books,” Jewel said. “You should come up and have a look at the sketches.”

She knew, of course, that he wouldn’t, for he cared so little about costume that, if she did not choose his clothing, he would shrug his thick short body into whatever in his wardrobe first caught his color-blind eyes. But he made up in kindness for what he lacked in style, and Jewel was grateful for his confidence in her judgment in that department.

“I’ll wait and be surprised at dress rehearsal,” he said. He stuffed the spotted handkerchief into his waistcoat pocket and came around the desk to engulf Bethia’s small hand with his two. “Do take care up at Cambridge. We’ll miss your sunny face about here.”

“Thank you, Grady,” she said. “I’ll see you in December.”

He escorted them out into the corridor. Mr. Birch, head attendant, was limping their way. Tall, white-haired, and stoop-shouldered, he could have been anywhere from sixty to a hundred years old, and had actually acted in small parts in his younger days at the Adelphi Theatre. “Ah, there you are, Miss Rayborn. A Mr. Pearce is in the lobby, asking for you.”

“Oh

no.

”

Jewel turned to Bethia. Her cousin was staring in the direction of the lobby, her face drained of color save two crimson slashes across her cheeks.

“What is it, Bethia?” Grady asked.

She blinked and gave him an apologetic look. “I’m afraid it’s Douglas.”

“My cousin?” Jewel said. “Why would he ask for you?”

Bethia drew breath. “We happened upon each other in Covent Garden two weeks ago. I had just seen Guy off at Waterloo Station and was window-shopping, trying to distract myself from a blue mood before going home.” She looked at Jewel. “You know how Mother and Father worry over me.”

“Yes,” Jewel said. She supposed it was because, now that

Uncle Daniel and Aunt Naomi had reached their golden years, they were more aware of the frailty of life.

“Mr. Pearce invited me to join him for tea in one of the shops,” Bethia continued. “I really would have preferred to be alone, but he was rather insistent. He said it wouldn’t be improper, as we’re somewhat related.”

“But of course,” Jewel assured her. After all, this was late 1897, less than three years away from a new century. Some of the more unreasonable chains of propriety that had bound their mothers were loosening. And Douglas and Bethia

were

distantly related, by the marriage of Jewel’s parents, with Bethia being on her father’s side, Douglas on her mother’s.

“Just explain that you have a beau,” Grady suggested. “And that, while he would understand meeting as you did by happenstance, he would object to a repeat of the occasion.”

“I’ve explained,” Bethia said in a flat voice.

“When?” Jewel asked.

“Many times.”

“You mean he’s courting you?”

“He sends me letters—sometimes more than one a day. He’s even knocked on the door at Hampstead. The second time, Father warned him not to come about anymore.”

Jewel traded worried looks with her husband. “Did he stop?”

“He stopped coming to the house.” Bethia frowned miserably. “Father doesn’t know that he followed me to the Royal Gallery Saturday.”

“Why didn’t you come to us?” Grady asked. “We could have helped you.”